Editor's Note: This review was originally published last year. Uncle Boonmee is now in theaters, ready to capitalize on its big win at Cannes... uh...10 months ago; way to strike while the iron is hot, distributors! If you're just getting a chance to see it for the first time, The Film Experience would love to hear any reactions.

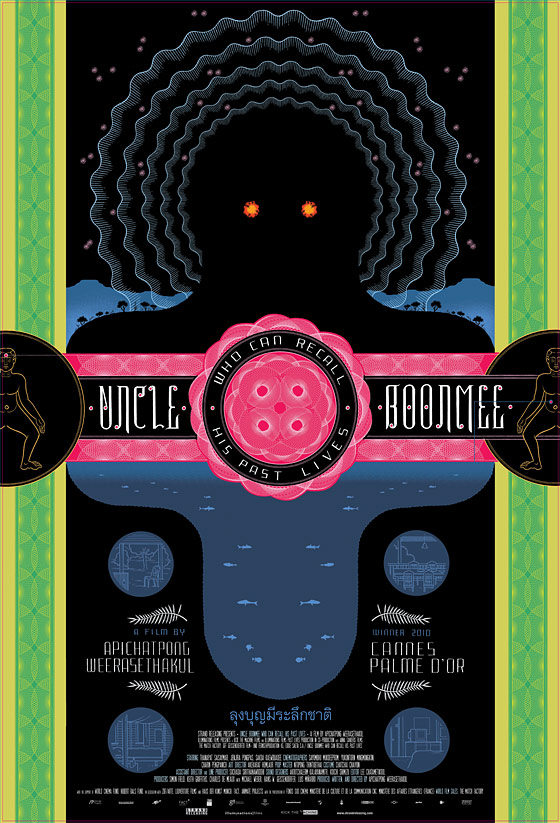

Uncle Boonmee can recall his past lives. My memory is hardly as uncanny. Recalling or describing Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, the Cannes Palme D'Or winner and Thailand's 2010 Oscar submission, even a few days after the screening is mysteriously challenging. Even your notes won't help you.

This is not to say that the movie isn't memorable, rather that its most memorable images and stories refuse direct interpretation or cloud the edges of your vision, making it as hazy as the lovely cinematography. You can recall the skeletal story these images drift towards like moths and you can try to get to know the opaque characters that see them with you but these efforts have a low return on investment. What's important is the seeing.

What's wrong with my eyes? They are open but I can't see a thing.

Most synopses of the movie will only embellish on the film's title. And while Uncle Boonmee does reflect on past lives, he only does so directly in the pre-title sequence as we follow him in ox form through an attempted escape from his farmer master, who will eventually rope him back in. The bulk of the film is not a recollection -- at least not from Boonmee himself, but a slow march towards his death while he meditates on life and the film meditates on animal and human relations. His nephew and sister in law, who objects to his immigrant nurse, visit him. So too does his dead wife and another ghostly visitor on the same night, in a bravura early sequence that as incongruously relaxed as it is eery and startling.

Most synopses of the movie will only embellish on the film's title. And while Uncle Boonmee does reflect on past lives, he only does so directly in the pre-title sequence as we follow him in ox form through an attempted escape from his farmer master, who will eventually rope him back in. The bulk of the film is not a recollection -- at least not from Boonmee himself, but a slow march towards his death while he meditates on life and the film meditates on animal and human relations. His nephew and sister in law, who objects to his immigrant nurse, visit him. So too does his dead wife and another ghostly visitor on the same night, in a bravura early sequence that as incongruously relaxed as it is eery and startling.

The film peaks well before its wrap with the story of a scarred princess and a lustful talking catfish and then we begin the march towards Boonmee's death, perhaps the most literal moment in the movie. And then curiously, the movie continues on once he's gone. If it loses much of its potency after Boonmee has departed, there are still a few fascinating images to scratch your head over when he's gone.

The bifurcated structure that Weerathesakul has employed in the past is less prevalent this time. Uncle Boonmee plays out not so much like two mysteriously reflective halves (see the haunting Tropical Malady which I find less accessible but actually stronger), but rather like a series of short films that all belong to the same continuous chronological movie, give or take that gifted horny catfish. Surely a google search, press notes, academic analysis or listening to the celebrated director Apichatpong "Joe" Weerathesakul speak (as I did after the screening) would and can provide direct meaning to indirect cinema. But what's important is the seeing.

Surely a google search, press notes, academic analysis or listening to the celebrated director Apichatpong "Joe" Weerathesakul speak (as I did after the screening) would and can provide direct meaning to indirect cinema. But what's important is the seeing.

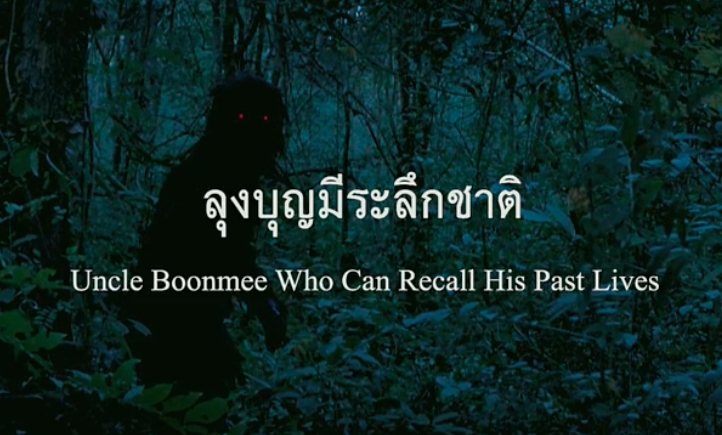

Vision is frequently mentioned and referenced in Uncle Boonmee, whether it's mechanical as in a preoccupation with photography or organic. But like the ghost monkey with glowing red eyes (the film's signature image) says to Uncle Boonmee early in the film, "I can't see well in the bright light." It's the one exchange in the film that I wholly related to and understood. I'm not sure I need or even want to understand, to attach specific meaning to these confounding stories and images. That's too limiting. I only want to see them. Weerasethakul's movie is best experienced in the dark, with the images as spiritual guides. They fall around you like mosquito netting as you walk slowly through the Thai jungle. B+