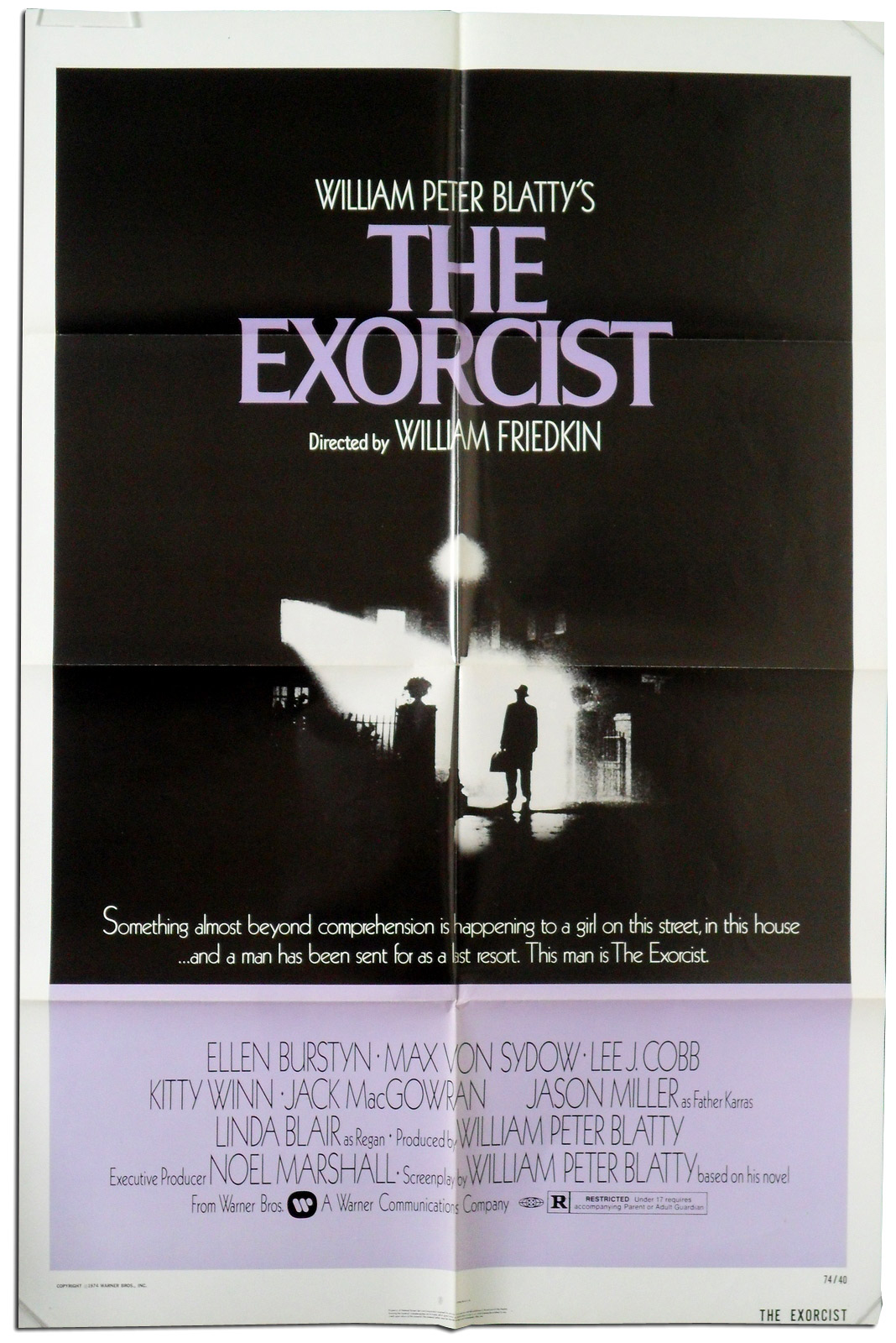

It's Amir here, brining you this month's poll. It's October so we're obligated to take you to the dark depths of cinematic greatness with a list of horror goodies. We're looking at the best horror films of all time, with a twist. We chose The Exorcist (1973) as our milestone since it's the first horror film nominated for the best picture Oscar and about to celebrate its 40th anniversary. So we've split the Best list in half, with The Exorcist as cleaver. Part two comes next Tuesday, but for now

It's Amir here, brining you this month's poll. It's October so we're obligated to take you to the dark depths of cinematic greatness with a list of horror goodies. We're looking at the best horror films of all time, with a twist. We chose The Exorcist (1973) as our milestone since it's the first horror film nominated for the best picture Oscar and about to celebrate its 40th anniversary. So we've split the Best list in half, with The Exorcist as cleaver. Part two comes next Tuesday, but for now

The Top Ten Best

Pre-Exorcist Horror Films

There really isn't much I can add by way of introduction, aside from pointing out that the boundaries of what is or isn't within the limits of this particular genre are blurry. Can Freaks still be considered a horror film today, removed from the initial shock of seeing circus performers with deformities on the screen in 1932? Cruel and unreasonable as it is, the appearance of the protagonists is the chief reason why such a passionately human piece of film history is considered scary at all - though as you will see below, one of our contributors has other ideas. No such questions would apply to Night of the Living Dead but what about Night of the Hunter? Hour of the Wolf? So on and so forth. The point is, take the genre categorizations with a grain of salt, but the suggestions to watch them very seriously. If you haven't seen any of these eleven films -- why is there always a tie? -- here's hoping this list persuades you to do so this October.

10. = Vampyr (1932, Carl Theodor Dryer)

There’s never been a horror movie with stronger art film credentials than this one, made according to the then in-vogue Surrealist style by a director who’d already created The Passion of Joan of Arc and had Ordet yet to come. But just because Carl Theodor Dreyer was a proper “artist” doesn’t mean that Vampyr’s pleasures are exclusively aesthetic. In fact, the same dictatorial control over image and space that makes Ordet a spiritual masterpiece makes this familiar story of one man’s journey through a creepy rural town living in fear of a bloodsucking old woman one of the most thoroughly unsettling things you will ever experience. It's more of a walking tour through a nightmare than a clear-cut narrative, with eerie shadows and shapes every which way and a profoundly moody score by Wolfgang Zeller that jangles one’s very last nerves.

-Tim Brayton

ten more spooky films after the jump

10. = The Birds (1963, Alfred Hitchcock)

What really makes The Birds terrifying are the ideas, rather than the action. The omnipresence and essential inanity of the creatures makes them a perfect, unbeatable, mysterious villain – are they even a villain at all? Hitchcock teases his audience by presenting several possible explanations, both scientific and allegorical, for the attacks, all the while knowing he never has to give an answer. He simply has to present the creatures as an incessant, terrifying force. As Melanie and Mitch walk back up to the school, they quietly pass the birds perching on the climbing frame, and soft, taunting calls echo like daggers. Whether a screech or a whoosh, a peck or a slash, the cacophony of sounds become simply nightmarish, with Hitchcock even muting the pain and dialogue of the family shut up inside the house as the birds attack from every side. Straightforward and elegant in both title and execution, The Birds provokes the idea that something we see everyday can unexpectedly become unfamiliar and horrifying.

-David Upton

9. Don't Look Now (1973, Nicholas Roeg)

Most horror movie tropes are easy to dismiss when the lights come up. We can laugh off a zombie or a wolfman. The deep psychic dread summoned by Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, however? I don’t know if you ever fully shake that. Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie travel to Venice to get over the horrific drowning of their young daughter but they can’t escape the specter of death as one foreboding incident after another accumulates around them. There are the bizarre psychic warnings, the corpse fished out of the canal, and the near fatal accident, but most disturbing of all Sutherland can’t stop having visions of his deceased daughter darting around Venice in her bright red raincoat. The film collects ominous details like random tiles in the mosaic Sutherland’s character is restoring. We despair of ever making sense of it all until, when we least expect it, the pieces align and form an image of ghastly, heart-stopping finality. Of course, by that time it’s too late.

-Michael Cusumano

8. Eyes Without a Face (1960, Georges Franju)

Eyes without a Face is grand, eloquent, horrible and dark. Real dark. Dark dark. It looks at the base experience of human depravity and the deeply pained and sacrificial provision of life that a father is willing to bestow upon his daughter. Oddly, it’s the pursuit of life, not death, that drives the film. The inherent terror and harsh beauty of Eyes is contained in its desperation. The film is filled with memorable, desperate acts. It’s brimful of tense and horrifying moments that prod us to feel both disgust and compliance. It’s sly, clever, engrossing; the trajectory of the plot never feels stable. That’s Georges Franju’s genius. He serves up both victims and perpetrators as fascinating, pitiable characters (and in horror these are the kinds of characters that thrill us the most). Eyes compels and disquiets in an austerely grandiose fashion. It has Alida Valli adding dark night work in a headscarf and pearls like a demented femme fatale who’s long traversed the wrong path. It also has an ethereal Edith Scob, lost and curious about the world, commanding both dogs and doves in a tragic symphony of release. And that music, cinematography and direction! Fifty-three years on, everything about Eyes without a Face is perfectly tuned to unsettle and undermine complacency with horror cinema.

-Craig Bloomfield

7. Cat People (1942, Jacques Tourneur)

Frenchman Jacques Tourneur began his phenomenal 1940s output with a trio of extraordinary RKO horror titles that were each heavily influenced by film-noir. Before I Walked with a Zombie and The Leopard Man (both 1943) came Cat People. Rooted in tradition and fables, Simone Simon stars as a Russian expat in New York whose carnal sexual desire sees her turn into a large black panther when aroused due to an ancient regional curse. Preposterous, sure, but Tourneur turns the film into a remarkable work of mood and atmosphere, it’s obvious B-grade beginnings largely forgotten thanks to a combination of sinister shadowplay and cunning soundtrack. Truly one of the best films I’ve ever seen, and one of the absolute scariest, too.

-Glenn Dunks

6. Freaks (1932, Tod Browning)

I watched Freaks by myself during an otherwise uneventful Saturday night at the age of 13. Seduced by the grotesque spectacle of the carnival performers, I watched in horror as the "normal" human beings turned out to be the film's true monsters. Tod Browning directs with a sensibility rarely seen in modern cinema, displaying real love for characters other directors would've made us fear. With hypnotic cinematography and an almost documentary-like feel, the film crawled under my skin to the point where the real surprise was that when the movie ended I was unable to leave my couch. I screamed and asked my mom to tuck me in bed that night. -Jose Solis

5. The Haunting (1963, Robert Wise)

Everyone knows what it's like to wake up in the middle of the night to strange noises, and no film does a better job of making you feel like the noises you hear are actually coming after you than The Haunting. We never really find out what malevolent presence is haunting Hill House, and why, but it doesn't really matter. What matters is the unbearable tension Robert Wise is able to create using little more than loud noises and a creepy-looking house; Elliott Scott's magnificent set was designed so that the rooms had no dark corners in which to hide, and Wise shot them with a lens that caused distortions, making them look even more disorienting. You may not be as susceptible to the paranormal as the fragile girl Julie Harris portrays here, but when that loud banging stops and that door starts caving in to impossible depths, you're right there with her, pulling your hair and begging loudly for it to stop. It's been years since I've seen The Haunting, but sometimes at night, when I'm in a strange room with the lights out, I can still hear those earth-shattering BOOMs, steadily getting closer... and closer... and closer... until I have to give in and turn on a light.

-Daniel Bayer

4. Nosferatu (1922, F.W. Murnau)

Part of why I love Nosferatu is because its images and its story turns feel scary in such a direct, even visceral way, and yet the more you learn about Weimar Cinema (as I was lucky to do from the great Eric Rentschler!), the more complex and culturally specific its signs and scares become. You feel like you're watching narrative film and new expressionist devices transform or invent themselves before your eyes—in the manner of a vampire who's suddenly just there, mutable and formidable at once. Meanwhile, you're also observing centuries of European lore, zeitgeists of the post-WWI moment, and upsetting recombinations of perennial scapegoats (not least some motifs from anti-Semitic art, which Murnau is debatably reprising or critiquing). The film has inspired virtually every bloodsucker film that came afterward, and plenty more films than that, plus some gorgeous homages in literature and cinema, and great Halloween costumes for bald guys. It gives you nightmares worth pondering and remembering.

-Nick Davis

3. Night of the Living Dead (1968, George Romero)

Night of the Living Dead may not be the scariest zombie movie.; it's corny as all hell, the acting is inconsistent, and the cinematography often leaves something to be desired. But without Night Of The Living Dead we wouldn't have the horror movie as we know it. Influenced heavily by The Last Man On Earth, this film birthed the first 20th century monster - the zombie horde. Before Romero, zombies were individuals cursed by black magic. After Romero, zombies were the science-created personification of modern society's fears. Everything from racial tension (Night of the Living Dead) to medical paranoia (28 Days Later) to consumerism (Dawn Of The Dead) have been examined in gory detail. Not a bad legacy for a no-budget monster movie.

-Anne Kelly

2. Rosemary's Baby (1968, Roman Polanski)

Rosemary's Baby is a film you can go back to over and over again and see something new and magical inside of every single time. Believe me I know of what I speak, I've been going back and re-watching it at least every three months or so since...oh, let's just say since I was born. (Birth being what matters.) I have forced more than one pregnant friend to watch the film with me. I started using Twitter back in the day just so I could live-tweet the film, and by "live-tweet" I mean "tweet every single line of dialogue one by one, because every single line of dialogue is a sheer and utter joy." But why listen to me? Go, watch the movie. I dare you to find an imperfect thing about it. John Cassavetes is too obviously outwardly evil from the get-go, you say? Bah humbug - that helps actively engage the viewer, because Rosemary's love for Guy hides what's so plainly right in front of her. Indeed us knowing what's coming works in the film's favor (and thus cements its status as "endlessly rewatchable") - that deep dark plummet Rosemary's primed for might be painted up with period-appropriate limes and lemons but it eats its way out from smack-dab center all the same. To the Year One, the year always - God is dead and the baby Adrian is home.

-Jason Adams

1. Psycho (1960, Alfred Hitchcock)

In a typically brilliant marketing coup, Alfred Hitchcock made the revolutionary decision to deny theater admittance to latecomers during the original release of Psycho. Such scrupulousness would lead you to believe that Psycho's legendary thrills reside in the unpredictability of its multiple narrative twists, but more than 50 years after it came out, is it actually possible to discover one of the world's most famous films without having already seen at least part of the shower scene? Is it possible to see it without knowing everything there is to know about Norman Bates' close relationship with his stuffy mama? And yet, Psycho stands; crown jewel of the Hitchcock canon, cornerstone of the horror genre, its power undimmed by years, multiple viewings, sequels, spin-offs, ripoffs and constant presence in pop culture imagery.

What's most fascinating about Psycho is how budgetary constraints breathed an entirely fresh creativity into a filmmaker whose stature and style were by then so firmly established. What other director can claim credit for creating an entire genre more than 35 years into his career? Widely held up as the first slasher flick, Psycho remains bone-chilling to this day partly because of its supremely perverse manipulation of audience identification: who could fail to root for gentle, desperate Norman when that stupid car refuses to sink? And while Hitch had already cracked the facade of many a vanilla actor by 1960, never had the cuts been so deep and transcendent as the ones he carved into Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh. But if Psycho remains unequalled in the crowded pantheon of horror films, it's ultimately the doing of two geniuses in peak form: composer Bernard Herrmann, whose blood-freezing score supplies at least as much narrative as the dialogue, and the director himself, whose unmatched confidence in his own storytelling and technique brims with the unexpected excitement of a child trampling his sandcastle to start building an even greater one.

-Julien Kojfer

Trivia

• More rental suggestions: Here are the films that finished in the 12th to 20th spots, in descending order: Bride of Frankenstein, I Walked With a Zombie, Night of the Hunter, Peeping Tom, Repulsion, Wicker Man, Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Dracula, Invasion of the Body Snatchers

• More rental suggestions: Here are the films that finished in the 12th to 20th spots, in descending order: Bride of Frankenstein, I Walked With a Zombie, Night of the Hunter, Peeping Tom, Repulsion, Wicker Man, Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Dracula, Invasion of the Body Snatchers

• The 40s and 50s aren't well represented in the list. In fact from 1940 through 1959 only Cat People is accounted for. Any titles you'd like to add?

• Only two of the films that placed first on individual ballots failed to make the final ten, a smaller number than all our previous polls. Is that indicative of broader consensus among our contributors? The two films were Night of the Hunter (Amir) and I Walked With a Zombie (Jason, Jose).

• This poll also had the second lowest number of films winning any votes after our Top Ten Comic Book Adaptations. Well then, yes, definitely broader consensus.

Which films would make your list?