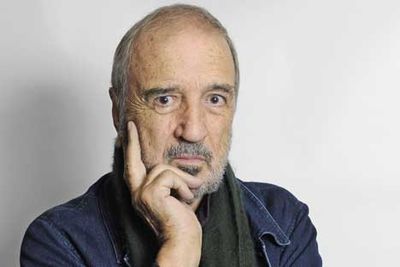

Our 2014 Honorary Oscar tribute series continues with a two-part look at the long fascinating career of Jean-Claude Carrière. Here's Tim with Part Two.

Yesterday, Amir did a wonderful job of introducing us to the supremely gifted and abnormally prolific Jean-Claude Carrière, focusing on his iconic collaboration with Luis Buñuel. As important as that work was for both men, it tells only a fraction of the tale. With nearly a hundred screenplays to his credit in a career that’s still holding steady, 54 years on, it’s simply not possible to reduce the full scope of Carrière’s contribution to cinema to his work just one collaborator.

And so we now turn to Carrière's writing in the years following Buñuel’s death. Given the transgressive, ultra-modern nature of their films together, it’s perhaps a bit surprising that Carrière’s output from the ‘80s to the present would be dominated by prestigious literary adaptations and costume dramas - what could possibly be less transgressive than that? But just as Belle du jour is nothing like the usual late-‘60s erotic drama, so are Carrière’s late-career period pieces only superficially akin to awards-bating fluff. 1979’s The Tin Drum, which he adapted alongside director Volker Schlöndorff and Franz Seitz, is one of the nerviest films about the psychology of Nazi-era Germany ever filmed. In the scenario he provided for Andrzej Wajda’s 1983 French Revolution film Danton, he built a foundation for an angry, vivid drama about the corruption of politics. These are confrontational films, even upsetting.

As the years progressed, Carrière perhaps mellowed, enough to pick up one final Oscar nomination for 1988’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which he shared with that film’s director, Philip Kaufman. Although even here, “mellowing” is a relative term.

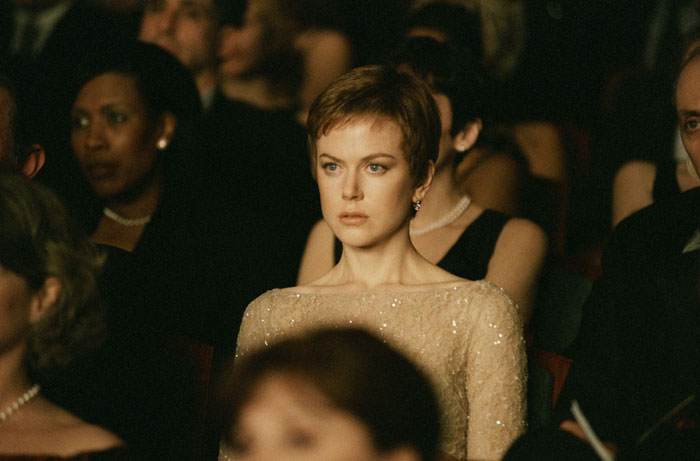

(The Unbearable Lightiness of Being, Birth, and Valmont after the jump)

While its unimpeachable literary credentials, based on Milan Kundera’s novel set during the Prague Spring of 1968, served as a cover for the skittish, conservative Academy of the late ’80s to feel good about rewarding the writers for taming the daunting source material into something that could function as a narrative motion picture, Unbearable Lightness is one of the most unapologetically grown-up films recognized by the Academy during that era. It is, once again, a script of blunt political engagement, mixed with a frankness about sexuality that never once shades into prurience. While it’s obliged to soften the novel’s dense philosophical underpinnings, even in a reduced form it’s thick with thoughts about morality, the complexities of love and monogamy, and the transience and temporality of existence (the “unbearable lightness” of the title).

Without being so overtly radical in its structure or content as his last collaborations with Buñuel, Unbearable Lightness is every bit their equal in its dissection of the mores of the European intellectual class. And Carrière and Kaufman’s depiction of the crushing effect of political repression on sexual and intellectual freedom alike manages to explicitly politicize the material without turning it into a simple “Communism sucked!” message picture.

Indeed, while I don’t pretend to prefer it to Carrière’s best films with Buñuel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being is arguably even more impressive an achievement in writing, since it manages to match those films’ intellectual highs without transforming into an outright intellectual exercise. It’s still, at heart, an audience-friendly character drama, one that gives ripe, full roles to Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, and Lena Olin to explore the wide range of dynamics of an unconventional sexual and romantic arrangement. By no means is it a generic crowd-pleaser, but it uses the form of mainstream prestige drama as a vehicle for digging into psychological and social relationships with the uncompromising directness of something more avant-garde. Easier to do that in a French production in the ‘60s and ‘70s than an American-financed film from the Reagan years, beyond a shadow of a doubt, and that Carrière was able to express themes which feel of a piece with The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and Belle du jour under those circumstances is absolutely impressive.

This would by no means be his last artistic triumph - the year after, he collaborated with Milos Forman to make the underrated Valmont, a spikier, snarkier, more Annette Bening’d version of the same source material as the same year’s Dangerous Liaisons, and in 2004, the 72-year-old co-wrote Jonathan Glazer’s Birth, a film which I do not have to justify to the readers of the Film Experience, I am sure. But in the years following The Ubearable Lightness of Being he’s never again had that kind of widespread, mainstream adulation again, and it is wonderful that the Academy is now taking the chance to honor all of the twists and turns of Carrière's life beyond the greatest hits.

Previously in The Honoraries: Maureen O'Hara, Hayao Miyazaki, and Harry Belafonte