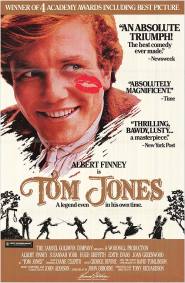

Andrew here to celebrate an anniversary. Fifty years ago tomorrow, Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones won the 1963 Best Picture Oscar at the 36th Academy Awards. Up until a few weeks ago it was one of my most glaring cinematic blindspots from that era.

Andrew here to celebrate an anniversary. Fifty years ago tomorrow, Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones won the 1963 Best Picture Oscar at the 36th Academy Awards. Up until a few weeks ago it was one of my most glaring cinematic blindspots from that era.

A cursory glance over the Best Picture winners of the 60s (ha, who am I kidding? I know the list by heart) reveals that by my faulty empirical research Tom Jones is easily the least discussed Picture winner from that decade today. Even Oliver, arguably the decade's least respected winner, seems more oft considered and it’s a curious thing because even ignoring the actual quality of Tom Jones it’s not business as usual as far as Oscar winners go. And, usually, we like to talk about when AMPAS throws us a curveball with its winners, for better or for worse.

Certainly, from an outsider's perspective it doesn't seem to be much of a curveball. What's the fuss about another period-piece turned Oscar winner? Although period films are lucky with awards they don't tend to be well remembered, or loved, on the internet. I could imagine what Tom Jones seems to represent to someone on the outisde looking in, another stuffy British drama Oscar bait film. (Something's that plagued Merchant Ivory films two decades after their heyday, but that's another story.) But, Tom Jones in all its unusualness has much to savour and enjoy, fifty years after its release.

Here are ten reasons to give it another or your first look...

10. Significant Best Picture Winner

Everyone who reads The Film Experience loves some good Oscar trivia. And Tom Jones has Best Picture related trivia to go around. It belongs to a number of elusive clubs re Picture winners. It’s one of only a dozen films financed exclusively outside of the United States to win the Prize. It's also one of the handful of purely comedic films to win the Prize. There would be some quibbling as to whether it's the most objectively funny but it certainly the most aggressively comedic Best Picture. Even the dramatic arcs are just comedic punch lines in hiding. It also rests with Shakespeare in Love as the only of two British period comedies to win Best Picture at the Oscars. Less positive, it's one of the very few Best Picture winners not nominated for editing, an unusual omission considering how heavily comedy depends on editing to land correctly.

9. Ambition and a Turning Point in British Films

Before Tom Jones, Richardson and his English contemporaries had concerned themselves with kitchen-sink dramas. Richardson's own Look Back in Anger and A Taste of Honey are two of the best ones. Tom Jones was not an angry young man of the era, although it's amusing how Richardson does present him as something of the sort. With its ambitiously zany stride Tom Jones, is rooted in escapism, signalling a move towards more light-hearted movies. Richardson places himself among his contemporary new-wave directors with the experimental way he shoots this period piece (more on that below).

But, apart from its place in its era, Tom Jones (and its hero Tom Jones) does much that’s unusual for cinema then and even for cinema now. Finney’s Tom prances about on-screen with significant devilish glances at the camera, distinctly aware that he’s in a film. The breaks in the fourth-wall (incidentally, like fellow comedic Best Picture winner Annie Hall), the droll overhead narration, the silent-film prologue, Tom Jones is a creature of its era yes but it's also a sign of a director firmly stretching his inventive talents.

8. Supporting Actress Trivia

For a very long time Tom Jones was a footnote in my Oscar pedantry due to its record-making actor trivia. In addition to being the film with the most acting nominations (five, tied with All About Eve, Peyton Place, and Network and five others) it’s the only film to ever earn three nominations for Supporting Actress - 60% of the whole category -- though none of them won. Oscar fanatics will remember that the only films to do the equivalent are On the Waterfront, The Godfather and The Godfather II which each earned three Supporting Actor nominations.

Sure it’s called Tom Jones (and also earned a supporting actor nod for Hugh Griffiths zany, supporting comedic turn) but Tom spends the film surrounded by women. If you go into the film knowing no names you would have a hard time guessing which three women came out with nominations. 1963 must have been such an unusual year for supporting actresses but even then the choice of nominees is fascinating. Susannah York as Tom’s intended and the female with arguably the largest role is not one of the nominated women. Neither is Joan Greenwood as a promiscuous, older noblewoman with whom Tom has a sexual liaison (Greenwood was, curiously, Golden Globe nominated). No, the three nominated women are Edith Evans serving Maggie Smith realness before it was a thing as Susannah York’s spinster aunt; Diane Cilento as the young “slut” (a word used with and for curious comedic effect throughout) in a slight role as a Sophia Loren-esque temptress and Joyce Redman playing a woman Tom saves from a Redcoat officer. Redman is easily the finest of the three but it’s a curious thing how slight, if hilarious, each of the three performances seem. As much as AMPAS liked Tom Jones, it didn’t get key nominations you’d expect (no nod for its costumes, editing, or its cinematography) making the triple nominations that much more curious. It’d be interesting to see how they’d be ranked in a Smackdown. (hint, hint)

7. Success with satire

Oftentimes it seems the only way to successfully do satire is with a strident dark tones. Nashville is one of the finest cinematic satires, Election and Fight Club are two very good ones. All of them are funny but never 'light'. Tom Jones is satirical and humorous and incredibly lithe and light, too. Tom Jones is one of the funniest films of the 1960s.

6. That sensual supper scene

A cursory glance over modern reviews of Tom Jones reveals a slight reluctance to give credit where its due to the film, the notion of the film’s bawdiness being potentially envelope-pushing today in its day but quaint today is echoed by a number of writers. But even as contemporary audiences would not find the same things surprising in Richardson’s adaptation, even time capsules have their merits. And it's not just a time capsule, either. Older films tend to need specific iconic scenes to serve as their beacon to future generations. In Tom Jones that's the feast from the second half of the film. Meal time has rarely been as sensual and I’d want to imagine that any pornographic film which uses food as the main aphrodisiac owes something to Tom Jones. Tom and Mrs Water dig into their meal with significant gusto making the moment delightfully comic while being distinctly seductive. The image of Joyce fellating chicken bone is worth it.

And, yes, the scene does (err) climax in a passionate embrace.

5. That musical score

If it were just for the opening scene – a five minute short film – I’d already be roundly impressed with John Addison’s score. Addison had previously worked with Richardson on Look Back in Anger, A Taste of Honey and The Entertainer. His work on Tom Jones is particularly exemplary. Music is a key element in telegraphing farcical elements to the audience and Addison’s sly and spry tones are as significant as the winking cinematography in pointing out the humour amidst the tale. Speaking of which….

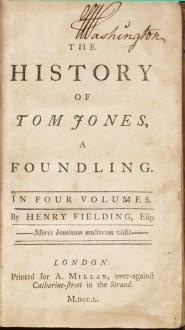

4. Its fidelity to Fielding's prose while remaining fresh

English playwright John Osborne (most famous for the excellent “Look Back in Anger” and its three adaptations) deserves much credit for his work on the screenplay. Henry Fielding, one of my favourite English writers, is an especially loquacious one and the source material for Tom Jones is about a 1000 pages long. You wouldn’t know it from this spry adaptation. Of course, there’s the caveat that the version of Tom Jones we’re presented with today is altered from its original version with some twenty minutes missing. Still, short as it is Osborne manages to condense the novel’s machinations while still retaining the tone of Fielding’s text. So many speak of Tom Jones as a "surprisingly" irreverent take on a stuffy English text but any bookish savant would know that Fielding was one of the first rebels of English prose. His works were considered much too sensational for his audience both for his satire and the sexual promiscuity within the texts. In adapting novels to film I often wish writers would strive for fidelity of tone more and less for fidelity of text. Adaptating Tom Jones into a 20 hour series would be of no use if the tone is lost and it’s Osborne’s screenplay keeps it intact. From there it’s up to Richardson and company.

English playwright John Osborne (most famous for the excellent “Look Back in Anger” and its three adaptations) deserves much credit for his work on the screenplay. Henry Fielding, one of my favourite English writers, is an especially loquacious one and the source material for Tom Jones is about a 1000 pages long. You wouldn’t know it from this spry adaptation. Of course, there’s the caveat that the version of Tom Jones we’re presented with today is altered from its original version with some twenty minutes missing. Still, short as it is Osborne manages to condense the novel’s machinations while still retaining the tone of Fielding’s text. So many speak of Tom Jones as a "surprisingly" irreverent take on a stuffy English text but any bookish savant would know that Fielding was one of the first rebels of English prose. His works were considered much too sensational for his audience both for his satire and the sexual promiscuity within the texts. In adapting novels to film I often wish writers would strive for fidelity of tone more and less for fidelity of text. Adaptating Tom Jones into a 20 hour series would be of no use if the tone is lost and it’s Osborne’s screenplay keeps it intact. From there it’s up to Richardson and company.

3. Walter Lassally cinematography

2. Richardson’s savvy direction

Usually when one speaks of films subverting our expectations it’s the narrative of the film being considered. Tom Jones would have been subverting notions of the British period film in the sixties and although I suspect some might see its more salacious inclinations as potentially quaint now they’re still unusual for the gusto with which they’re attacked. But even as the narrative subverts typical constraints of its era, Tom Jones is all the more impressive for the way its technical aspects are supporting the subversion too.

Tom Jones does not LOOK as you’d expect a film from this era or about such things to look, even if it’s a comedy. Richardson's direction is a credit to the film’s New Wave roots where it’s carrying itself atypically but even today key aspects of what Richardson is doing with direction and especially Lasally is doing with his camera are surprising and impressive. Just as with the editing, Tom Jones was not nominated for its cinematography even though it's the best technical aspect of the film. Key among the photography and editing is an exhilarating fox-hunt which is shot with a shaky-cam that is usually used to reveal a heated war scene or some such battle. Narrative-wise the moment is incidental, but a quarter way into the film it reiterates the point that this not a tale of genteelness but the raw, if hilarious, underbelly of the upperclass. Frame after frame Tom Jones is sumptuous to behold and excellently directed.

1. Albert Finney

All the goodness mentioned till now would be for naught if the actor embodying Tom Jones did not work. The best thing about watching older films is considering where they may have seeped into current film and there are aspects of Tom Jones subtly found in some aspects of today’s ribald comedies: the promiscuous, but loveable male lead and his quest for the virtuous woman’s hand. It’s a….problematic conceit but one which Fielding’s source and Richardson’s film both manage to get away with. Finney’s charm is invaluable here. It’s a gem of a performance and of the 1963 nominees I've seen, my favourite. Finney is acutely aware of the satire that he’s in and plays it as such. For all the exasperating vacuousness he elicits Tom’s sincerity and that's paramount.

Also, he’s easy on the eyes.

If my shoddy research is accurate Tom Jones sits alongside Patton, Chariots of Fire and Gandhi as the least discussed post 1959 Oscar Best Picture, so I’m assuming many of you have not seen it. If not, now’s as good a time as any to seek it out.