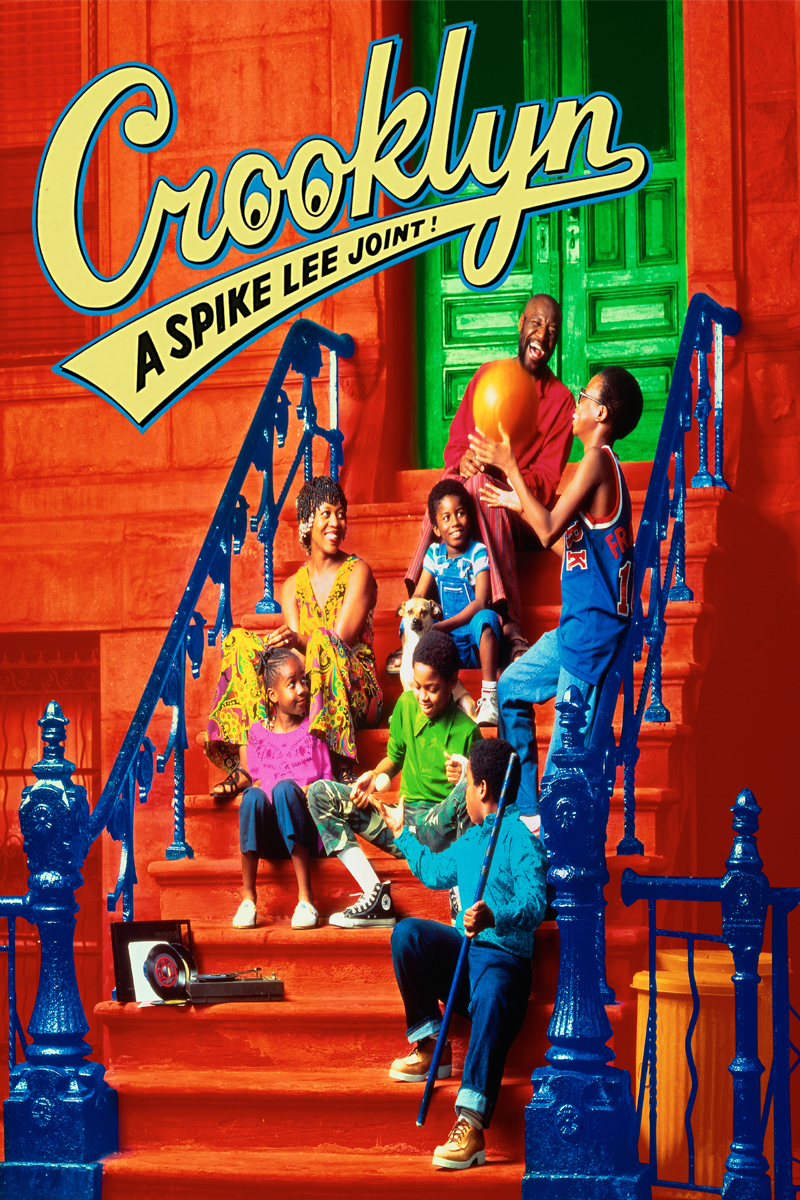

TFE is celebrating the three Honorary Oscar winners this week. Here's Kieran discussing one of Spike Lee's warmest and most underappreciated films.

For better or worse, you can often feel a larger thesis statement, be it about race and/or American culture at large, running through much of Spike Lee’s work. His films also feel incredibly male in their perspective. Even his few films that foreground women (She’s Gotta Have It and Girl 6) feel enveloped by the male gaze, despite their many other virtues. These are just a couple of reasons why Lee’s semi-autobiographical slice-of-life dramedy Crooklyn feels like a bit of a curio.

For better or worse, you can often feel a larger thesis statement, be it about race and/or American culture at large, running through much of Spike Lee’s work. His films also feel incredibly male in their perspective. Even his few films that foreground women (She’s Gotta Have It and Girl 6) feel enveloped by the male gaze, despite their many other virtues. These are just a couple of reasons why Lee’s semi-autobiographical slice-of-life dramedy Crooklyn feels like a bit of a curio.

Crooklyn is set in the summer of 1973 in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, where Lee himself grew up. Nine-year-old Troy Carmichael (Zelda Harris) is the only girl in a brood that includes four rowdy brothers. Though often put-upon and teased, Troy is tough, clever, funny and every bit the daughter of her equally strong-willed mother, Carolyn (a radiant Alfre Woodard). More so than any other film Lee has directed, Crooklyn is wholly interested in the inner-life, motivations and perspective of its female characters. Even Woody (Delroy Lindo), the family patriarch and easily the most fleshed out male character in the joint still feels like an afterthought compared to how focused the narrative is on Troy and Carolyn. How Alfre Woodard's anchoring performance failed to garner any Oscar traction is confounding, especially when one looks at the outlet mall fire sale irregulars that were the Best Actress nominees of 1994.

The “angry black man” label that Lee has garnered, fairly or unfairly, burdens the reception to a lot of his work. And yet, it seems when he leans away from that, critics and audiences alike are still at sea as to how to respond. Not to say that Crooklyn is categorically absent of any critiques or observations of blackness and anti-blackness in America. The Carmichaels have a neighbor, Tony Eyes (David Patrick Kelly) who emblematizes this. His frustration at the Carmichael boys dumping their trash in his rubbish cans seems couched in seething resentment of the fact that he has to live so close to so many black people; a dynamic not exactly subtle in how it’s rendered. And yet, there’s an uncommon warmth, humanity and light touch running through Crooklyn. This feels tonally refreshing when held up against Lee’s other work, particularly coming off the heels of Malcolm X, released two years earlier.

When Troy goes to visit relatives over the summer, Lee employs an oft-discussed (when this film happens to be discussed) technique of altering the framing. The picture looks squeezed together, meant to represent how Troy, a born-and-raised New Yorker experiences the expansive suburbs of the American South. It’s incredibly distracting, but also endearing as it’s an example of how the movie isn’t afraid to be fully in this girl’s experience. One can’t help but admire how he film has the courage of its mercurial convictions.

Many of Spike Lee’s films have a sort of purposeful looseness to their structure. This style is used to great effect in Crooklyn. There’s so much odd, colorful specificity running through the piece. A scene in which Troy buys candy at a local bodega and watches Connie (RuPaul in a brief, but memorable cameo) dance seductively and frenetically with a Puerto Rican customer to Joe Cuba’s “El Pito” stands out. It’s such a strange and funny moment that has no bearing on the rest of the film and can only have been birthed from something Lee witnessed as a child. There are a lot of frisky and playful moments like this in Crooklyn, though neither of those are adjectives that one typically conjures when considering Spike Lee and his work.

Though it has gained a bit of a cult following, Crooklyn was not a success in its time. It tanked at the box office and is not routinely ranked among Lee’s best work, though it surely deserves to be. It’s right up there with Do the Right Thing in terms of a singular and personal work by one of his generation’s most important filmmakers.