TFE is celebrating the three Honorary Oscar winners this week. Here's Lynn Lee on one of Spike Lee's most controversial joints...

TFE is celebrating the three Honorary Oscar winners this week. Here's Lynn Lee on one of Spike Lee's most controversial joints...

Is Spike Lee an Angry Black Man? Reductive as the label is, it’s hard not to associate with an artist as reliably outspoken as he is accomplished—if only because so much of his best work is fueled by genuine anger at the condition of African Americans and the state of American race relations generally. The irony of having achieved major critical and commercial success by channeling those frustrations surely hasn’t been lost on him, even if it’s done nothing to diminish them.

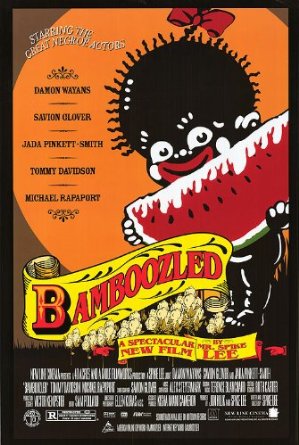

Bamboozled (2000), an incendiary, balls-to-the-wall satire about a disaffected black man who creates a pop culture monster, shows Lee at his angriest and most conflicted. The film takes its cue from Malcolm X’s famous wakeup call:

You’ve been hoodwinked. You’ve been had…You’ve been bamboozled”

It tells the tale of a Harvard-educated black TV writer (Damon Wayans, sporting a deliberately outlandish pseudo-French African accent) who pitches a hideously racist modern-day minstrel show as a fuck-you response to his white boss’s demand for “blacker” material—only to have the show become a megahit despite, or rather because of, the controversy it causes. [More...]

If Spike Lee was hoping for a similar response to his movie, he didn’t get it. Launched as a cultural firebomb, it merely fizzled, both at the box office and among critics, before disappearing into the obscure corners of Lee’s filmography.

It’s not difficult to see why. Shot mostly on digital video back when DV was used to convey gritty immediacy, and 16mm film, the movie looks cheap, relying heavily on the strength of its ideas and performers. While most critics admired the boldness of the concept, most, not unfairly, took issue with its execution. To its detractors, it’s an over-the-top, incoherent screed, and even to its defenders (including me), it’s simultaneously heavy-handed and scattershot in its satirical marksmanship, to the point that it’s not always clear what is, or rather, what isn’t a target. Just about everyone and everything comes in for a withering dose of contempt: the odious white network executive (Michael Rapaport, perfectly cast) who fancies himself an expert on what is authentically “black”; the lily-white, utterly clueless young writing staff; the gimlet-eyed media/PR consultant hired to put a positive PC spin on things; the appropriation of hip-hop culture by white folks and their marketing departments (the “ghee-to-fabulous” Tommy Hilfiger, hilariously if unprintably renamed, gets an especially hard beating); the black militants who bring the show to a violent end but who are also dumber than a box of hair; and, of course, the prissy, pretentious, self-hating main character, Pierre Delacroix, who insists on calling blacks “Negroes” and aptly compares himself to Dr. Frankenstein for creating a monster that his ego prevents him from destroying. While Delacroix bears no resemblance in personality or product to Spike Lee, one can’t help reading into the character an ambivalence about being a black entertainer who’s also seen as capable of “selling” his authenticity to a larger, white audience.

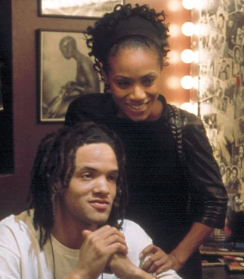

The only major characters allowed any degree of dignity are the ones who suffer the deepest indignities: Manray (tap and funk dance phenom Savion Glover) and Womack (comedian Tommy Davidson), the street performers who are cast as the leads of the show, and Sloan (Jada Pinkett-Smith), Delacroix’s assistant, voice of reason, and therefore doomed Cassandra. Their rise and fall feels overdetermined, and the last act may strike some as unconvincingly melodramatic, even if the entire trajectory pays obvious homage to Network and its spiritual predecessor, A Face in the Crowd. Still, at its best “Bamboozled” is a scathingly funny takedown of everything that’s wrong with a white-dominated entertainment industry that exploits black culture while denying blacks agency over how they’re represented. That theme continues to have resonance today, though one wonders whether Lee’s perspective might be affected by the huge popularity of Lee Daniels and Shonda Rhimes and the more modest success of shows like “Blackish” (which sounds a lot like one of Delacroix’s failed shows).

Still, even if the overall outlook has improved, Bamboozled stands as a powerful testament and rebuke of how deeply racism is embedded in the history of blacks in American entertainment. Watching Manray and Womack clowning around grotesquely in blackface and bright red lipstick, acting out the crudest possible caricature of “two real coons” (that’s a quote, I swear) on an Alabama plantation, is something that has to be seen to be believed. It never loses its peculiar horror no matter how long you watch, as underscored by Davidson’s searing, unexpectedly moving exit scene. The same goes for the other jaw-dropping iconography Lee slips into the movie, not at all subtly but highly effectively, as Delacroix fills his office with vintage racist knickknacks, curios, and collectibles and watches clips from old movies and TV shows peddling the same offensive stereotypes that he repurposes for his own show.

Some critics have charged that all this racist imagery is overkill, and that its repulsiveness undercuts the plausibility of such a show succeeding in modern times. I see it differently. The fact that we can’t view such imagery without feeling queasy is not something we should take for granted. In the words of one of the characters, it reminds us of a time we should never forget. And for that alone, Bamboozled remains worth watching—both in our time and for generations to come.

Some critics have charged that all this racist imagery is overkill, and that its repulsiveness undercuts the plausibility of such a show succeeding in modern times. I see it differently. The fact that we can’t view such imagery without feeling queasy is not something we should take for granted. In the words of one of the characters, it reminds us of a time we should never forget. And for that alone, Bamboozled remains worth watching—both in our time and for generations to come.