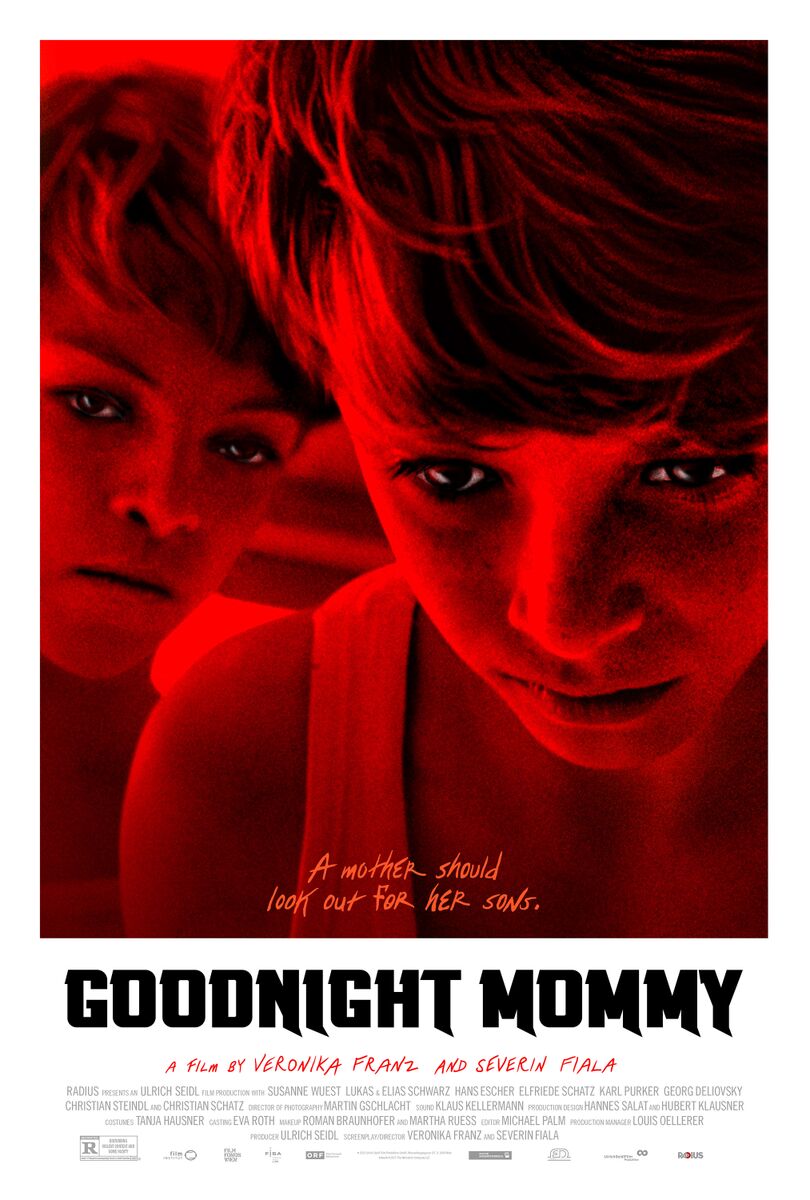

Jose here. In the terrifying Goodnight Mommy, two angelic twin brothers named Elias and Luke (played by Elias and Luke Schwarz respectively) become convinced that their mother has been replaced by someone else after returning home from a stay at the hospital. And who can blame them? Their mother (Susanne Wuest) returns wrapped in Franju-esque bandages that only show her eyes, and she seems to have lost her good temper, patience and tenderness. Terrified of this unknown person, the twins proceed to torture her in order to get to the bottom of things. Directed and written by the team of Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, Goodnight Mommy is the kind of horror film that creeps under your skin because of how committed it is to its aesthetics and points of view.

Jose here. In the terrifying Goodnight Mommy, two angelic twin brothers named Elias and Luke (played by Elias and Luke Schwarz respectively) become convinced that their mother has been replaced by someone else after returning home from a stay at the hospital. And who can blame them? Their mother (Susanne Wuest) returns wrapped in Franju-esque bandages that only show her eyes, and she seems to have lost her good temper, patience and tenderness. Terrified of this unknown person, the twins proceed to torture her in order to get to the bottom of things. Directed and written by the team of Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, Goodnight Mommy is the kind of horror film that creeps under your skin because of how committed it is to its aesthetics and points of view.

There is not a single body-horror line Franz and Fiala are unafraid to cross, and the film features torture involving everything from superglued eyes to bondage by bandage; however, there is not a single moment in the film that feels gratuitous, and just like a song would serve a musical, the torture we see onscreen serves the story because it makes sense that these children would be terrified of someone they believe to be a total stranger, and if anything Goodnight Mommy has more in common with Home Alone than with Saw, if not in tone, at least in its intentions. The film has been selected to represent Austria at the Academy Awards and opens in the States on September 11. I had the chance to sit down with the filmmakers to discuss their techniques and tips for working with children, their favorite horror movies and what AMPAS members they wish to scare the most! Read the interview after the jump.

JOSE: You might not like to hear this, but I don’t remember the last time I went to a press screening and half the people were covering their eyes…

(Veronika laughs out loud)

JOSE: however, it was interesting because the images you two composed are so beautiful! Can you talk about the film’s aesthetics and creating beautiful images that people might want to look away from?

SEVERIN: We tried to make a film that people would want to see. Our art is different from other people’s because we like being challenged by film. It’s good that we make you look away sometimes.

VERONIKA: It’s good if you get so tight that you don’t even dare to look at the screen. We like this tension, it’s a body experience.

SEVERIN: That’s what film is made for, we come from Austria where there’s a long theatre tradition and theatre counts more than cinema in terms of culture, so in Austria people lean back and watch this cultural thing and thinking about it intellectually all the time. We like cinema because if it’s good it’s impossible to think about it intellectually while watching it, it affects your body too much, draws you into the story.

VERONIKA: It overwhelms you! In terms of aesthetics we moved into the house where we shot the film with our cinematographer, Martin Gschlacht, and tried to build the images there.

SEVERIN: We were there at different times of day seeing how the light affected the space and then storyboarded them. In the evenings we would watch horror films to inspire us.

VERONIKA: Our cinematographer hates horror films and kept saying working on this has been the most frightening experience he’s ever had. He’s done more than 30 films! He’s worked with Shirin Neshat and Jessica Hausner among others, so he’s a very experienced cinematographer. The day we shot inside the cave with the bones, he said it was the worst day of his work life.

SEVERIN: (Laughs) ...actually with the children it was different. Because we shot this next to a real cemetery where people throw the bones of people whose graves aren’t being taken care of anymore. So the bones in the film were real! We were afraid we wouldn’t be able to shoot there, but the priest told us it wasn’t a holy place anymore, they were just bones. We were afraid that the children would react strongly, but they didn’t care at all. Martin was terrified though.

VERONIKA: We wanted the beginning of the film to feel nightmare-ish or fairy tale-ish because it was seen through the children’s eyes, we changed that for the last part of the movie where they torture the mother, we used more handheld cameras to change the aesthetic a little bit.

I like that you brought up fairy tales because the film is a rejection of the Disneyfied notion that children are saints and that fairy tales all have happy endings, because original Grimm stories are so gruesome!

VERONIKA: The original Grimm tales were so bloody! In one of them people were hanging from trees, so Goya used it as inspiration. I always skip that part when I read them to my children (laughs).

SEVERIN: There is also a tale about a boar who lives in the woods and the King says that whoever kills it will get to marry his daughter, so there’s two brothers, one’s evil the other’s good, and the evil one kills the good one and makes a flute out of his bones. Every time someone plays the flute it screams about the murder, that’s one of my favorites.

VERONIKA: Children see the world in a different way, their world is filled with nightmares, so we wanted to show this.

I’m aware that most of the symbols and meaning in screenplays usually come from the unconscious, but I’m really curious about the names of the children in the movie, because Luke and Elias are the two biggest prophets in the Bible. And in a segment of the Book of Luke there is the famous “Transfiguration” where the ghost of the prophet Elias manifests, and your film plays with these concepts of appearances, foreshadowing and identity so much that I wonder if the names were indeed taken from those people.

VERONIKA: We sadly have a very banal answer to that really sophisticated, intelligent question. In the screenplay we didn’t give them names, and Elias and Lukas are the actors’ real names, so we told them they could choose the names of their characters and they chose to use their own names.

This is a question I should save for their parents then!

SEVERIN: (Laughs) Yeah! Their parents are great people, she’s a psychiatrist and the father is a doctor. They never read the screenplay, they trusted us. We told them it was a horror film, shot it and we showed them the film when it was ready. We were so nervous when we showed it to them, and they loved it! They’re proud of the film and the children.

Since the film was shot chronologically I’m sure it was a relief that their mother is a psychiatrist, which probably helped you relax, but how did you prepare the children for the journey?

VERONIKA: They experienced it as a game, we moved with them into the house so they wouldn’t think of it as a stage. We gave them the basic situation: your mother is back from the hospital and you’re not sure if it’s really her. It was important for us to keep their interest, because we wanted them to be natural and authentic. If we’d asked them to learn lines or rehearse for weeks they would have lost some of that, so on a daily basis we gave them bits and pieces of the story. It was hard to keep the truth about the mother from them because they are so intelligent.

SEVERIN: If you think of all the violent, disturbing things in the film, when you shoot it, it actually feels more like a game to them, because you need to be very precise with the technical parts. What looks really violent onscreen requires a lot of work and is really technical, it’s like sports, you need to keep control of your body, so the shooting wasn’t stressful to them, they kept saying it was the best summer of their lives. The last day of shooting which was really long and cold, we were afraid they would ask us to stop, instead when we finally cut, they started crying and said they wanted to go on shooting the film.

VERONIKA: We were putting together the extras for the DVD and we found some footage some crew members had shot of the kids shooting one of the most difficult scenes, in which they’re poking the mother’s eye.

SEVERIN: It looks really ridiculous, and that’s how it felt when we were shooting it! As directors we needed them to show emotion with their faces, but they never experienced anything disturbing. Peter Kern in an image from 'Kern' That’s the magic of movies! This is your first fiction feature length together, but you did a documentary on Peter Kern a few years ago - I was so sorry to hear he died recently - it might be too early to ask this since you’ve only done two films together, but watching Kern I couldn’t help but notice he was like a child, a big child, and Goodnight Mommy deals with the same, they’re both films about outlandish children trying to shape the adult world to see what they want to see.

Peter Kern in an image from 'Kern' That’s the magic of movies! This is your first fiction feature length together, but you did a documentary on Peter Kern a few years ago - I was so sorry to hear he died recently - it might be too early to ask this since you’ve only done two films together, but watching Kern I couldn’t help but notice he was like a child, a big child, and Goodnight Mommy deals with the same, they’re both films about outlandish children trying to shape the adult world to see what they want to see.

VERONIKA: That’s so interesting of you to say, because we actually think that as different as the movies are if you look at them superficially, they actually have many things in common.

SEVERIN: You’re the first person to say that and you’re so right, they’re both about identity and trying to get to the inner core of the person, of looking behinds masks.

VERONIKA: Also this thing about being a child is true, I think Peter Kern would be really proud to hear you say this because that’s how he saw the world, of course he would first try to fight you, but then he would have laughed.

Did he have a chance to watch Goodnight Mommy?

SEVERIN: Yes, he liked it very much, but in typical Kern fashion he said “I would’ve never expected you two idiots to make such a good movie”.

(Veronika laughs)

SEVERIN: Kern was the least successful film in Austria when it came out, it was only seen by 482 people!

VERONIKA: It had a nice festival career, but whatever, we wanted to make a film about him and we didn’t care if nobody came to see it. We had a very small budget and we did it because we were convinced someone had to make a film about him.

SEVERIN: We’re interested in playing games, not only with the audience but also with each other and our subjects. It makes film shooting less boring.

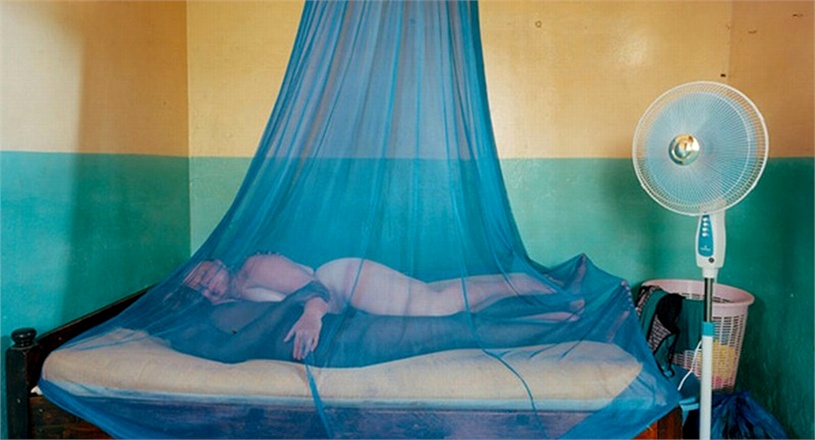

A still from 'Paradise Love' which was co-written by Veronika Franz

A still from 'Paradise Love' which was co-written by Veronika Franz

Veronika, before moving on I need to ask about writing the Paradise trilogy which I feel has many horror elements, which you and Ulrich Seidl never cross. So was working in Goodnight Mommy an opportunity for you to push these boundaries?

VERONIKA: Working with Ulrich is almost the complete opposite of working with Severin. When I work with Ulrich we write the story but it has no dialogues, it’s like a short story, everything is described in detail but Ulrich improvises the dialogue, he’s inspired by original locations and by the actors and actresses. You can’t predict what will happen, so you have the structure, but then a lot of scenes are added while shooting. We rewrite during the shoot, it’s a work in progress all the time. Working with Severin we wrote everything in advance, it’s a genre film so we needed the scenes in advance, otherwise the film wouldn’t work.

SEVERIN: I think part of the challenge is to not make the actors feel that, to make it feel natural, never staged. As a director you have to figure out a way to get them to do what you want, without saying it out loud.

VERONIKA: As far as stepping over borders, it always comes out of reality, you just exaggerate it a little bit. Ulrich relies on reality so much, in Paradise: Love everything could be real, he kinda stylized it with his framing, but what the film is about we got to doing research in Kenya for three years.

Perhaps that element of reality is what makes them scary.

VERONIKA: Yes!

You mentioned that you wanted to make a movie you’d want to see. Most modern horror movies are pretty terrible, they’re not scary and rely too much on jump scares. What do you think about the current state of horror films? Do you ever go see a horror movie and actually get scared?

SEVERIN: There are very few good horror films nowadays, but horror is the best genre to really talk about stepping over borders. Many arthouse films that touch on similar topics lose the audience because they’re not interesting.

VERONIKA: We watch old horror films, they’re our school. Films like Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, Otto Preminger’s Bunny Lake is Missing, Re-Animator by Stuart Gordon, Society by Brian Yuzna. Severin always liked Invasion of the Body Snatchers, I also like Nicolas Roeg, we don’t try to tell films apart by art or horror, we just like good films. Horror films are better than most genres because if they’re good they talk about death, grief, changes in family...so they are very existentialist.

I also feel that even the bad horror movies represent the current state of society in a way that romantic comedies don’t for instance.

SEVERIN: That’s the only genre we don’t like!

Many times when a movie as violent as Goodnight Mommy comes along, the angry villagers show up and accuse them of teaching people about violence. Recently I was listening to an interview Wes Craven did decades ago in which he talked about how hypocritical it was to be shocked by violence, when countries in Western society often start wars, invade other countries and such.

VERONIKA: We loved Wes Craven! Yes, horror movies and films in general are a mirror of society. Good films try to be honest.

SEVERIN: Romantic comedies are never mirrors of society (laughs).

VERONIKA: No, they are mirrors too. They talk about longings and dreams.

SEVERIN: Things that don’t interest us.

They also help perpetuate old fashioned values.

VERONIKA: Yeah, they’re very white, heterosexual stories. Maybe we should make a romantic comedy about lesbians.

Speaking of men, you completely remove the father figure in Goodnight Mommy, can you talk about the reasons behind this.

SEVERIN: We had to eliminate him, there was a short scene in the film which we shot, but we cut when we edited it, because we wanted the film to concentrate on the smallest family unit. We wanted it to be about this core.

VERONIKA: The mother in the film is a single mom, she’s raising them by herself.

During the past decade we have seen more movies about the relationships between mothers and children exclusively, which I find fascinating because somehow we are still constantly being fed this idea of the traditional family when we know the truth is much more different. I found it really heartbreaking for the mom because even though she has her own problems, she also has to deal with these demonic children. I actually said to someone that the movie was the best birth control method I’d seen.

VERONIKA: (Laughs) To me, like you said, people think men are supposed to be in charge, but it’s the women who raise the children. People think mothers are supposed to always know what’s best for the children, and actually I have two boys myself and you don’t always know! It’s a challenge to raise children, the mother in the movie is a TV person, I used to be a journalist, and it’s challenging to combine your profession with raising children sometimes. Sometimes I feel as if it’s the children who are in charge, they tell you what to do! In modern society those are issues which aren’t talked about, as a mother you have to know, and if you don’t know you’re a bad mother! But you can only know what you learned from your own upbringing, and maybe that upbringing wasn’t so good. Nobody helps you raise children, you don’t have a gene for that. I believe raising children is a profession, some people have the talent for it, and some people are less talented.

I agree with you, and in the film we see that transference of power between parents and children. In countries like Germany and Austria for instance, we see children carrying the sins of their parents and grandparents, and in art we end up seeing the same kinds of apologetic movies about the Holocaust, but then we see that in reality Europe hasn’t moved very far from it. There’s a very strong reactionary, right wing movement growing again.

VERONIKA: Actually I find it very interesting that Germany and Austria are receiving all the refugees with open arms, I think it’s guilt from the Holocaust. The rest of Europe for instance isn’t accepting them, Great Britain closed its doors, Spain said they don’t want them, but Germany and Austria are taking them.

SEVERIN: That’s why we start our film with the Von Trapps singing…

Which is so scary by the way.

SEVERIN: (Laughs) Yes! It’s supposed to be scary, we were scared too. And this was meant to be the image of the perfect Austrian family, everyone singing together. We still carry around this idea of the family being something perfect and holy.

VERONIKA: It’s also this thing about what families bury and don’t wish to dig up or talk about. For us as Austrians for instance, Germans confronted themselves for Nazism and worked through it, but Austrians did not. For decades they pretended to be victims of Hitler, and it was only about 20 years ago when the Austrian Chancellor accepted our guilt. People didn’t talk about it before, they buried it.

SEVERIN: Our tagline is, “from the country that brought you Hitler and Haneke…”, but nobody thinks it’s funny.

Speaking of which, like some of Haneke’s films, your film has been selected to represent Austria at the Oscars. Are you excited about that?

SEVERIN: We are proud that it’s the first horror film Austria submitted, so we were quite surprised about that. Most people seem to feel we already won an Oscar, so they congratulate us all the time.

VERONIKA: It’s a national honor, you start with a nadir and you end hoping you’ll win an Oscar.

For all we know, in the least you’ll end up giving nightmares to George Clooney and Meryl Streep!

VERONIKA: We hope so!

Goodnight Mommy opens in theaters tomorrow.