Manuel on an unlikely double feature he’d like to dub “How I Mourned Your Mother.”

In his TIFF coverage, Nathaniel mentioned that film festivals sometimes offer you random thematic threads born out of unlikely juxtapositions. This was the case when I caught Nanni Moretti’s Mia Madre and Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie almost back to back. Both films are concerned and inspired by the death of the respective filmmakers’ mothers. The results are as widely different as you’d imagine and fascinating for wildly different reasons.

In his TIFF coverage, Nathaniel mentioned that film festivals sometimes offer you random thematic threads born out of unlikely juxtapositions. This was the case when I caught Nanni Moretti’s Mia Madre and Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie almost back to back. Both films are concerned and inspired by the death of the respective filmmakers’ mothers. The results are as widely different as you’d imagine and fascinating for wildly different reasons.

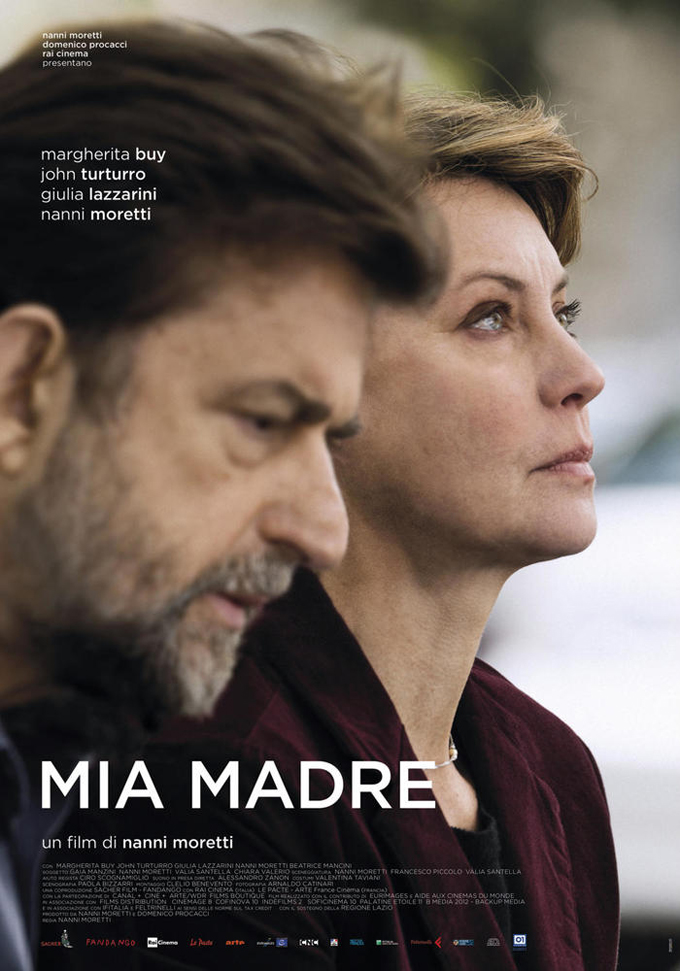

Moretti’s Mia Madre opens with a scene of laborers rioting against their factory’s owners. Workers chant and fight against armored policemen in riot gear. And then Margherita (an effectively understated Margherita Buy) yells “Stop!” She’s shooting a film, as it turns out and she’s not too happy with the framing she was getting. We slowly learn her personal life is taking a toll; she’s broken up with her boyfriend and her mother is slowly dying at the hospital. You can almost imagine the press about that shoot (“Director’s Personal Issues All But Ruined the Production”). [More...]

The film, a personal project for Moretti as he disclosed in the press event after the screening, was inspired by his own loss during the editing of his most recent film, 2011’s We Have a Pope. Playing Margherita’s brother Giovanni, Moretti casts himself as the person he wished he’d been: while the film director is pushed to get on with her shoot, dealing with a loudmouth American actor (John Turturro) who can’t remember any of his lines, Giovanni tends for their mother dutifully. There’s perhaps too much to unpack in Moretti’s film, which swings wildly between full-on farce (Turturro chews scenery with gusto, relishing the chance to play a blow hard actor who loves telling a story about being hired by Kubrick omitting the small detail that he’d later been fired by the famed director himself) and an affecting meditation on death (it never quite teeters into Amour territory but that’s because, as Moretti noted, he never wanted to hold the audience hostage over such grueling scenes of death and decay).

Nested within these narratives are concerns about filmmaking (that opening scene has Margherita asking her AD whether in offering close-ups of the bashing cops he wasn’t implicitly aligning the audience’s empathy with the bashers and not with those being bashed), about language (Margherita’s mother was a beloved Latin professor who relishes the chance to tutor her own granddaughter on proper translations), about politics (the film is about union-busting, a social conscience film Margherita starts losing faith in the more she shoots it), and about memory (as if failing to keep herself grounded, the director is constantly flashing back to moments she wished she could take back). As autobiography-as-fiction, it is a fascinating piece of atonement and one easier to unpack by those who’ve followed Moretti’s career. Given the Academy's predilection for Italian movies and for movies about movies, Moretti's film may strike a chord should it be submitted for the Foreign Language Film Oscar.

Akerman’s No Home Movie goes the opposite direction, valuing stillness and emptiness over narrative and dialogue. It opens with an static shot of an arid landscape with a tree in the forefront. The wind roars. Minutes go by. The wind continues to roar. This goes on for quite sometime. Someone at the theater walked out. Those first few minutes feel like a dare.

There’s a way of talking about No Home Movie as a taxing experience. At just under two hours, much of it transpires in silence, with Akerman’s camera lingering on shots of empty living rooms, and open roads. There’s an intentional mundanity to the setting; this is a film in mourning, or a film about anticipating mourning; much of the dialogue is riddled with reminisces. It is elegiac in the way it seems to anticipate its subject’s death, valuing silence and emptiness.

There’s also a way of talking about Akerman’s film as self-indulgent. This is, after all, a documentary made up of scraps of furtively shot Skype conversations, and candid interactions with her mother that depend on a total indifference to the camera. That we get several moments of Akerman’s mother openly stating she’d rather not be filmed, hoping to be able to say things to her daughter she’d rather not have shared with other people, push a discomforting feeling about whose project this is and why it’s being made. In many ways, you’d expect it to be all about celebrating Akerman’s mother (like Bernstein’s look at Nora Ephron, say) or about wanting to uncover something new about her (as is the case in the Ingrid Bergman doc, In Her Own Words, also screening at the festival). Instead, No Home Movie is much too obfuscating about its central figure that one can only conclude that this is a film for and about Akerman herself. It is a feature-length film about those extended “Au revoir, Mama!”/ “Au revoir, Chantal!” that greet their Skype conversations and which go on for minutes on end, as if they both knew saying goodbye was to be an ongoing and neverending charade.

Its long stretches of “boredom” are, of course, the point, but the film may be too fragile and tinny for many people’s tastes. Where Moretti’s film reimagines his mother’s death in his own image through fiction, Akerman’s edits herself into her mother’s last moments in ways both intrusive and distancing. As a pair they did nothing more than making me want to call my mother right away which is, perhaps, the best they could both hope for.

Mia Madre screens at NYFF on September 27 and 28th, while No Home Movie screen on October 7th and October 8th.

Mia Madre screens at NYFF on September 27 and 28th, while No Home Movie screen on October 7th and October 8th.