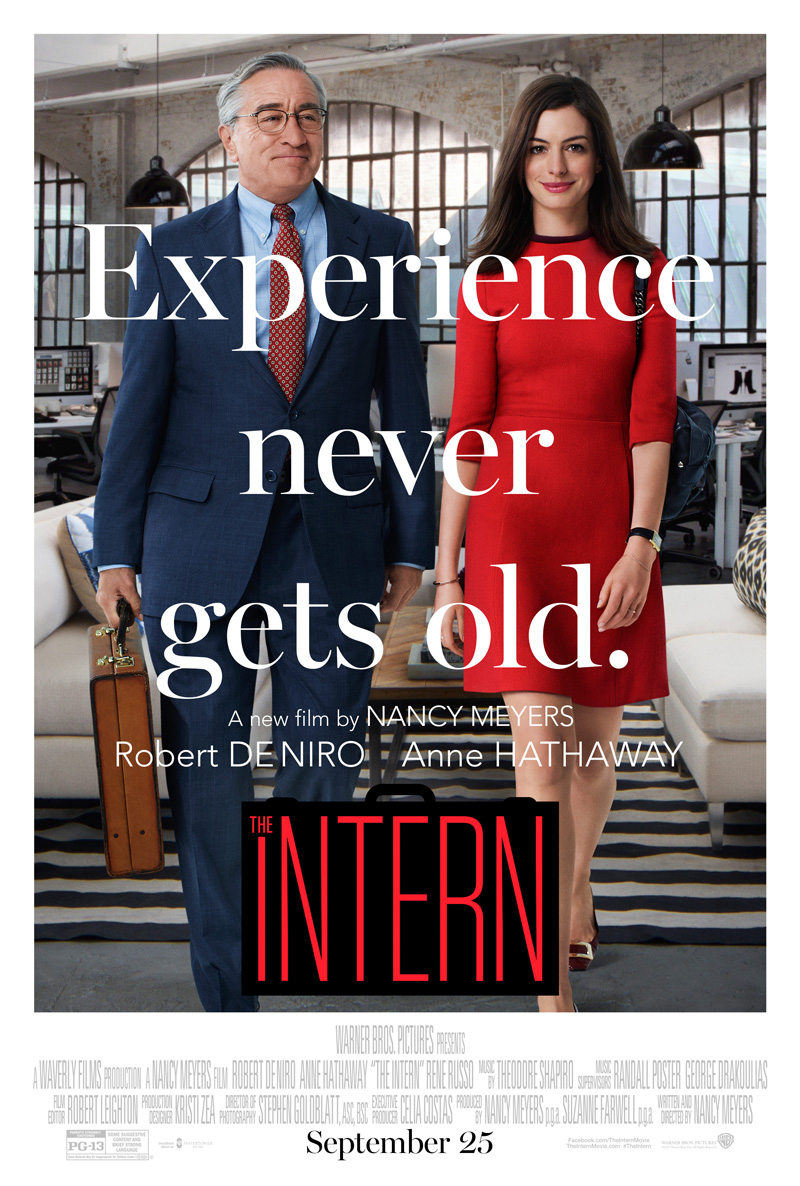

Kyle Stevens, author of Mike Nichols: Sex, Language and the Reinvention of Psychological Realism is here to review Anne Hathaway's latest.

The Intern follows 70-year-old and retired Ben, played by Robert de Niro (who has never seemed more like a Bobby). Having enjoyed a happy and prosperous life, Ben now finds himself so uninspired by endless leisure activities that he decides he deserves another go on the merry-go-round. He lands the film’s titular position at a women’s clothing startup created and run by Anne Hathaway’s Jules, who, we are told, is a difficult woman to work for despite all evidence to the contrary. Ben and Jules become friends, as Jules realizes that even an old be-suited, briefcased, handkerchief carrying man—the icon of conservative, 1950s patriarchy—may have worth. Disturbing as this is, especially at first, The Intern gives us a real man-woman friendship—that rarest of on-screen sights, even if it is here rendered “safe” by Ben’s age.

De Niro and Hathaway shine, particularly in a hotel scene that gives them time to plumb the depth of writer and director Nancy Meyers’ characters. Meyers is one of our best character writers, but The Intern’s frenzied workplace setting doesn’t afford us time to fall in love with her creations as we did in, say, Something’s Gotta Give (2003), where Meyers simply put the camera in front of Diane Keaton and let her go. [more...]

That said, the film plays to Meyers’ fans. Like Something’s Gotta Give, it features a stony, male character anxious about his age and heart health and a flinty, ambitious female. As in The Holiday (2006), there is an attempt to recuperate old vocabulary from a supposedly more genteel era. And, of course, there is a lot of beige and slate blue. And I mean a lot.

However, I think it’s a mistake to see the story as an excuse for objectionably privileged viewers to ogle lux décor, as many critics have done. In the 1930s, even during the worst days of The Great Depression, movie audiences eagerly huddled into theaters to see comedies with beautiful people wearing beautiful clothes in beautiful rooms. Such visions were a collective fantasy, an escape. Nowadays, if you’ve read any of the reviews of The Intern or mentions of Meyers, you know that both are taking a lot of heat for offering images of fashionable abodes unobtainable to the masses. Even Jeff Goldstein at Warner Bros. (who is distributing the picture) said:

Nancy Meyers really is a brand onto herself [sic]…It’s not just the stories that attracts people. It’s the lifestyle, it’s the sets, it’s the clothes.”

And he’s right. This is what appeared when I Googled “Nancy Meyers movie”:

But craving a kitchen that would make Ina Garten green can be just a fantasy. It doesn’t necessarily mean that such audience members resist the equal distribution of wealth in reality, though I realize that this is a fine line. My concern is that the critical animosity about Meyers’ interest in “lifestyle” has to do with the fact that she is a woman. Meyers clearly follows in a tradition of Hollywood Cukor-wannabes, such as Walter Lang and James L. Brooks. But where Brooks has a style, Meyers is a brand.

Beige and slate blue is not just a ritzy, beachy color combo. It evades screaming “feminine” or “masculine” to audiences steeped in today’s gender codes. Meyers’ stories need this. She gives her characters a fair place to play, work, love, and fight. Even though it’s not a romantic comedy, in The Intern, Meyers retains the traditional Hollywood romantic comedy’s narrative conceit of mapping professional and personal success onto one other. One cannot be happy with money or romantic love alone, she tells us again and again. One must have both. In Meyers’ cases, characters tend to put work first, or learn to do so. This premise provides a somewhat feminist cast to her pictures, but, at the same time, it takes on quite a troublingly neoliberal perspective. For instance, if they want to succeed in their jobs or in their sex lives, the non-Ben interns must learn to dress “like men,” not boys. At first, I was taken aback by this. What’s wrong with jeans and hoodies? Who would ever want to bring back the social customs that suits and briefcases symbolize? But given The Intern’s many explicitly feminist statements, it seems odd for Meyers to endorse such obviously conservative values. Perhaps she is asking us to think about how we might use the wisdom and style of the past, and make it our own.

There are real, live questions about the relations of gender and age and aspiration, and of all that to capitalism running throughout The Intern, and they’re dealt with in complex ways. So why are critics just talking about credenzas and clothes?