It's Noirvember. Here's Lynn Lee...

For a film set in the ’50s, L.A. Confidential (1997) looks and feels surprisingly contemporary. Maybe it’s because so many of its themes still resonate today: police brutality (especially against racial minorities), broken Hollywood dreams, and the addictiveness of celebrity and power. Maybe it’s because so much of the film is shot and lit in a more naturalistic, less stylized manner than your typical hardboiled crime movie, which makes the more obviously noir-ish sequences really pop by contrast. But I think what distinguishes it most from its classic forbears is that it ends up being less memorable for its atmosphere or its plot twists than its character development of not one detective-protagonist but three, whose parallel narrative lines end up converging over the course of the film.

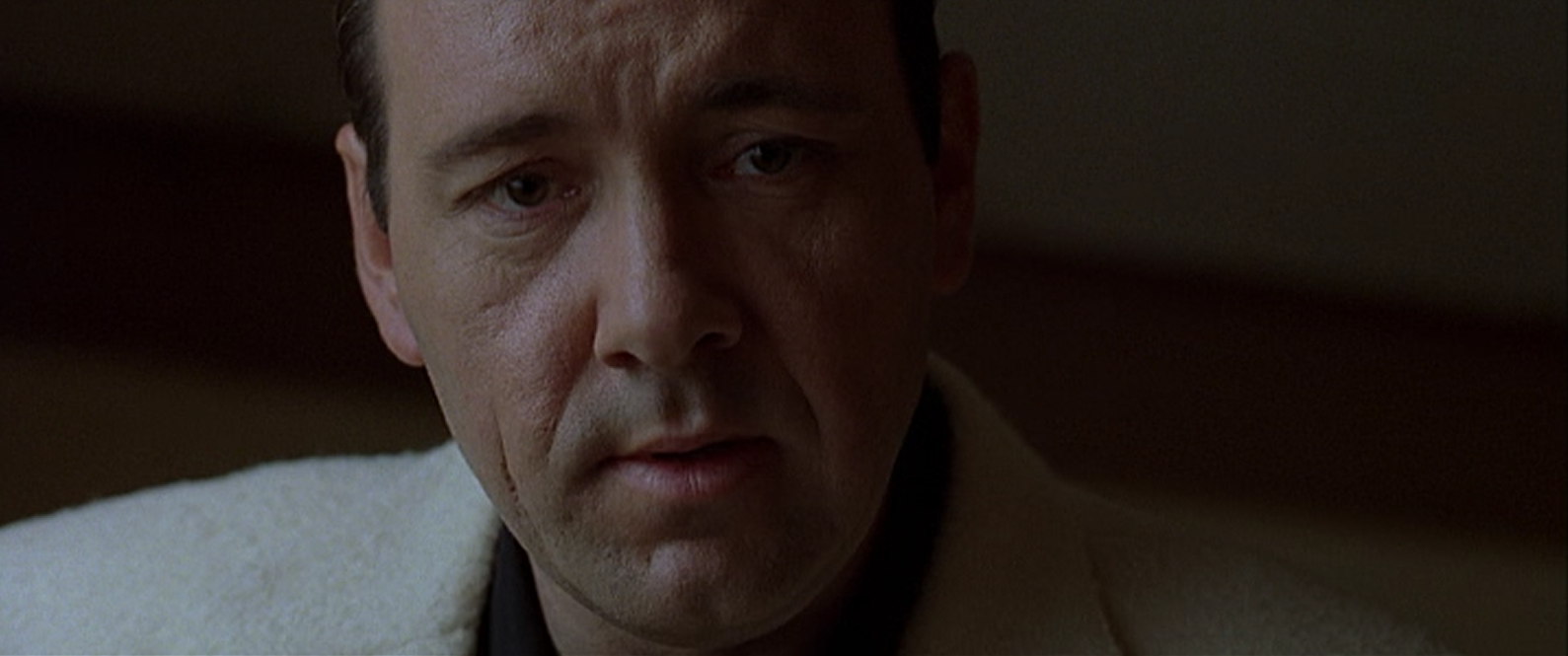

It’s a neat trick that’s equal parts strong writing and strong acting. I often point to L.A. Confidential as one of my all-time favorite ensemble films, thanks to exceptionally well-drawn characters who even in just a few scenes rise above one-note archetypes. Brian Helgeland nabbed a well-earned screenplay Oscar for adapting and streamlining James Ellroy’s notoriously dense novel, while Kim Basinger took home best supporting actress, although I’d submit the other actors around her, who didn’t get nominated, were even worthier. In my opinion, L.A. Confidential should have won both picture (sorry, Titanic fans) and actor, and also deserved a nod for James Cromwell for supporting actor. Of course, having three co-leads – Kevin Spacey, Russell Crowe and Guy Pearce – probably doomed its chances for best actor, even if Crowe and Pearce had been better known at the time. They’re all brilliant performances, and they play off and boost each other so effectively it’s hard to single out one. Though if I had to choose one I’d go with Crowe, who somehow manages to make his psychologically damaged cop with a savior complex a simultaneously brutal and sensitive figure, shifting seamlessly from one to the other and back again with just a look in his eyes.

One of the many pleasures of the movie is the way it sets up Bud White (Crowe), Ed Exley (Pearce), and Jack Vincennes (Spacey) as complete contrasts in their policing sensibilities and motivations (think id, superego, and ego of the LAPD, respectively), only to complicate the picture and gradually reveal them to be much more similar than initially apparent. Early on, after an ugly police beatdown on Hispanic inmates makes the news and launches an internal investigation, there’s a series of three back-to-back scenes in which Bud, Ed, and Jack are separately interrogated by the disciplinary board and demonstrate, in a nutshell, what makes each of them tick. Bud’s is the shortest; true to police code as well as his own personal code of loyalty, he curtly refuses to cut a deal and rat out anyone, even if his silence means maximum punishment for himself. Ed, the ambitious rookie, is only too eager to testify against his fellow officers, piously intoning “Justice must be served” while offering a politically shrewd strategy by which the LAPD can mitigate the public outrage at minimum cost to its ranks. Finally, completing the triptych, “Hollywood” Jack initially refuses to testify against anyone, only to capitulate almost immediately when he’s threatened with having to forego his post as consultant to a TV crime show if he doesn’t cooperate.

These stark divisions begin to blur with the arrival of the central mystery, a mass murder at a diner that Ed ostensibly “solves,” netting him further glory, but quickly begins to suspect was a setup. So, as it happens, does Bud, who recognizes a connection between the murders and a high-class porn and prostitution ring called Fleur de Lys. Jack, meanwhile, finds his long-dormant detective instincts stirred by guilt after his desire for a payoff and a news headline leads to the murder of a young actor (Simon Baker) with ties to Fleur de Lys.

It’s at this point that each of the three protagonists begin to question whether he’s really the kind of cop he wants to be, and whether he can break the mold in which he seems pre-set. We see Bud, in a tender scene with one of Fleur de Lys’ call girls, Lynn Bracken (Basinger), wrestling with what to do about the Nite Owl kllings:

If I could get a chance to work homicide like a real detective…That prick actually shot the wrong guys. I know it in here. [strikes his chest] There’s something wrong with the Nite Owl. I’m just not smart enough to prove it. I’m just the guy they bring in to scare the other guy.

But, as Lynn points out, he’s actually been doing good detective work so far, and he goes on to do more, carving out the first path to the real killers.

Meanwhile, Ed’s been having his own identity crisis: we next see him gazing at the medal he received for resolving the Nite Owl case, clearly racked with doubt. Learning that Bud is on to something about the Nite Owl (and piqued by the discovery that the man he dismissed as a dumb animal is one step ahead of him), he decides to recruit Jack to help find out what it is. Tellingly, he comes upon Jack looking at a news clipping of his first “bust” of the actor whose death he caused, his expression an echo of Ed’s stare at his medal. The movie underlines that consonance when Jack sardonically asks why Ed would want to go digging into the case that made his reputation.

ED: I wanted to catch the guys who thought they could get away with it. It was supposed to be about justice…then somewhere along the way, I lost sight of that. Why did you become a cop?

JACK (somberly, his face going blank): I don’t remember.

From that point on, the three parallel threads begin to merge, as Ed joins forces first with Jack, and later with Bud, to unravel the mystery. All three end up showing dimensions that not even they could have anticipated. Jack, the cop who was only interested in celebrity, dies an unsung hero. Bud, valued only for his brute force, proves a smart sleuth. And Ed, the self-proclaimed man of principle, turns out not to be above an extrajudicial killing and cover-up if it’s ultimately in the service of justice. At the same time, the three prove to be less different from one another than they initially supposed: at bottom, they’re all good detectives who want to get it right. Cop redemption isn't a novel concept for a noir film, but its execution here is nearly flawless, and all the more intriguing for being threefold. It’s one of the main reasons I keep returning to the movie and finding it so rewarding each time.