"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

In movies, if perhaps not in life, people can be driven mad by mountains. In films by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, they can be driven mad by paintings of mountains.

Black Narcissus is the story of a group of Anglican nuns who trek up to an abandoned cliffside palace in the Himalayas to establish a new convent. Deborah Kerr, cinema’s most consistent nun, is Sister Clodagh, the young mother superior. Her mission is doomed from the beginning, of course, though not necessarily because the locals reject their presence. Rather, it is the landscape that overwhelms their emotions and breaks their faith and their vows.

Powell and Pressburger did not shoot on location in India, however. The set was built at Pinewood Studios. [More...]

The long establishing shots of the remote palace were done with a combination of models and matte paintings, a perfect example of that breathtaking falseness that we only rarely find in today’s world of digital effects.

The sets fall under the purview of production designer Alfred Junge, who won an Oscar for the film. He had also worked with the Archers on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and would later work with Kerr on the utterly bizarre Edward, My Son. The mattes were by legendary British painter Walter Percy Day, another regular collaborator of Powell and Pressburger. Their work is both luxuriously detailed and extremely assertive.

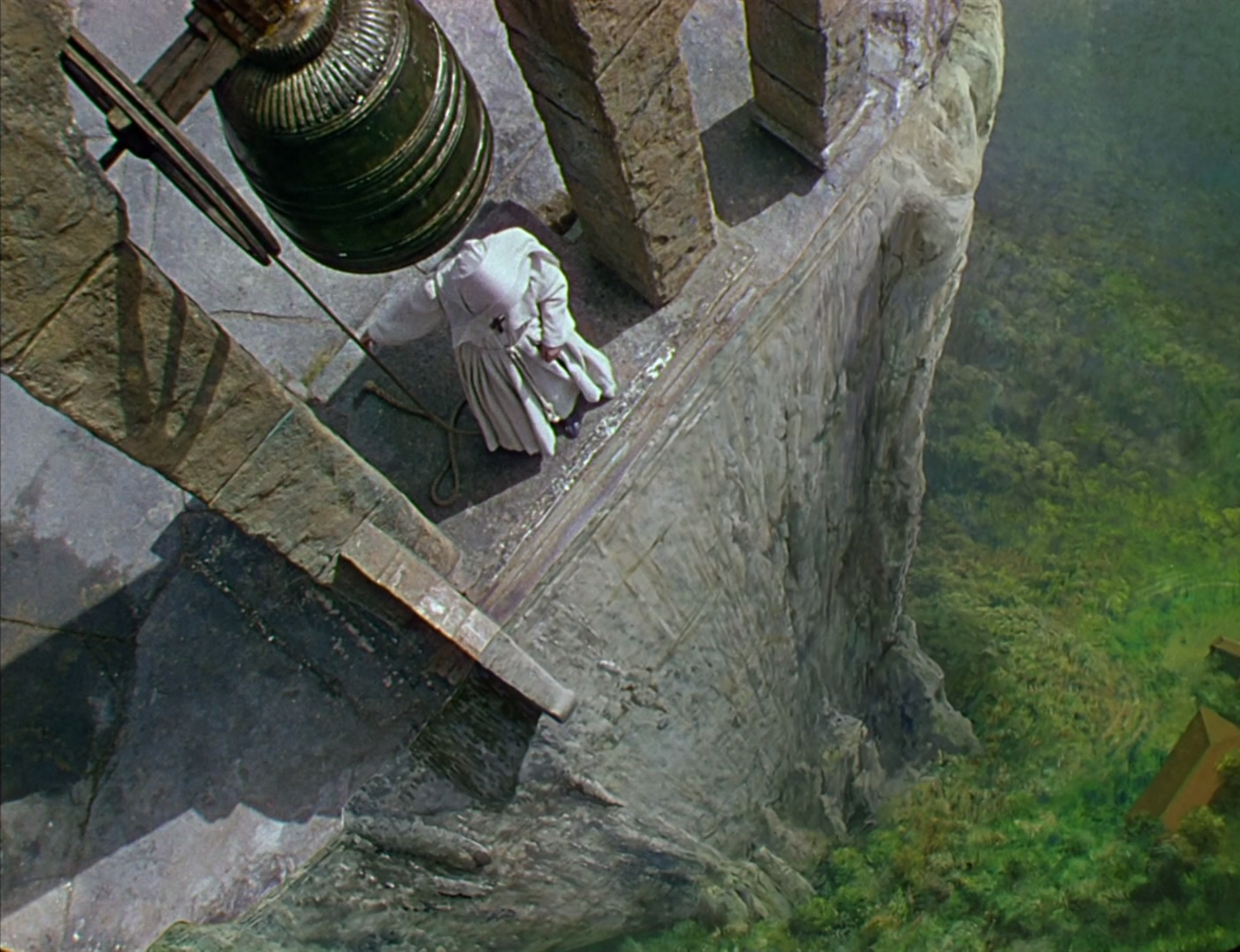

The most memorable use of these paintings the famous shot of the drop down from convent’s bell, which hangs just next to the edge. But Day’s paintings are everywhere, constantly reminding us of the vast landscape that takes more than the breath away from these sisters. Sister Philippa, for example, is so entranced by the sky that she loses her ability to work her garden. Overcome with emotion, she replaces all of her vegetables with flowers.

The building itself is no escape, either. Surrounded on three sides by nothing but the fresh air of the mountains, Day’s paintings find their way into nearly every shot. They peer into the yard, through the small windows of the chapel, and draw our eye even from Kerr’s quaint monastic sleeping cap in this shot of her cell.

As Sister Ruth goes mad, the mountains underline her distress from beyond the enormous windows of the school room. The scene is gripped by a malevolent dusk, perhaps the best example of the way cinematographer Jack Cardiff’s lighting aligns with Day’s images.

Even in the few rooms where the sky cannot interfere, nature often holds sway. Though the building is full of wall paintings of scantily clad women, a holdover from its harem days, the abstract walls of the central chamber are even more entrancing. Its lush blue frescoes take the power of the Himalayan exterior and morph it into a floral delirium.

For Sister Clodagh, this constant stimulation results in flashbacks to her life before the veil. The blue of the sky takes her back to the blue of an English lake, where she once fished with her sweetheart. While she may not actually go mad, her monastic resolve is certainly weakened by the landscape’s constant suggestion of beauty and desire.

For context, their original Calcutta convent is devoid of such distractions. There are no paintings, either inside or outside. The walls are bare and white. Instead there are electric ceiling fans, among the film’s few garish reminders of the 20th century. The blunt corners of their cross-shaped dining table are far cry from the flowing lines of the Himalayan landscape to follow.

And so it is perhaps obvious from the beginning that these nuns are out of their depth. But the film does not show all of its cards so early, instead using the beauty of the matte paintings and the sets to gradually increase the tension. It is not until that terrifying dusk finale that the entire world seems gripped by panic and dread. The mountains and the sky redden accordingly.

Finally, as Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth struggle beneath the bell, clouds descend. All is cold and gray. The matte paintings have done their job, slowly creeping up on the nuns until the resulting psychotic break drives away their hue. There is nothing left but to give up and go home, return to the colorless houses of the established order and relearn the quiet peace of unchallenged faith.

Previously on The Furniture:

Deadpool (2016), That Hamilton Woman (1941) The Lady in the Van (2015), Joy (2015), The Exorcist (1973)