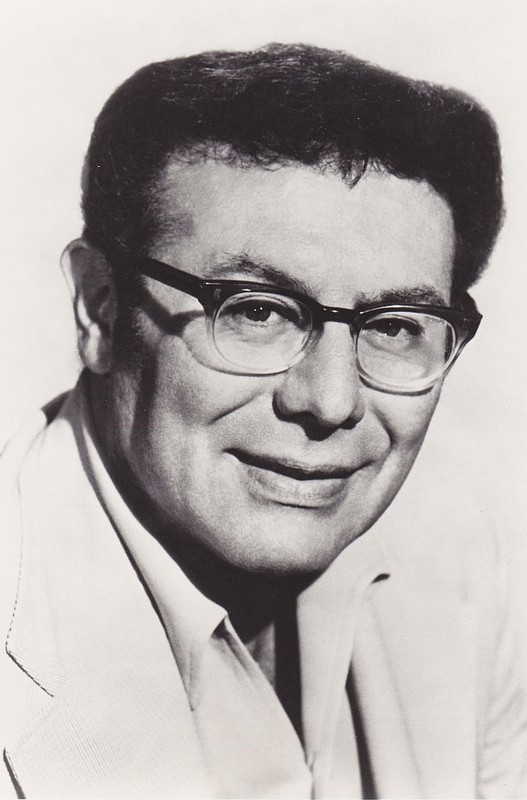

Tim here. Today we celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the birth of producer-director-writer Irwin Allen, one of the great junk-food purveyors in Hollywood cinema. It's by no means true that Allen invented the disaster movie (a genre stretching back into the 1930s), nor even the uniquely '70s-style incarnation of the form, with an impressively well-stocked larder of overtalented, underpaid stars filling out the clichéd melodramas of addiction and marital strife that tend to form the plots of these movie (Airport got there first). But it was under Allen's hand that disaster movies became the greatest, gaudiest spectacles of the decade.

Tim here. Today we celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the birth of producer-director-writer Irwin Allen, one of the great junk-food purveyors in Hollywood cinema. It's by no means true that Allen invented the disaster movie (a genre stretching back into the 1930s), nor even the uniquely '70s-style incarnation of the form, with an impressively well-stocked larder of overtalented, underpaid stars filling out the clichéd melodramas of addiction and marital strife that tend to form the plots of these movie (Airport got there first). But it was under Allen's hand that disaster movies became the greatest, gaudiest spectacles of the decade.

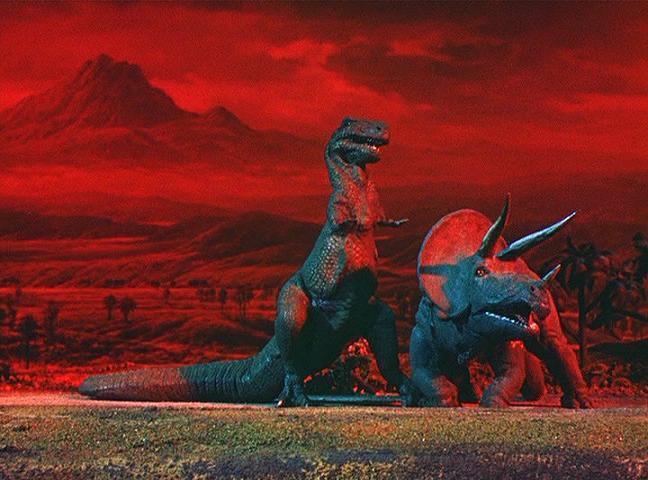

Allen was not always a high-end schlockmeister. In fact, he began his career as an Oscar-winner, taking home a Best Documentary Feature award for 1953's The Sea Around Us, based on a Rachel L. Carson book. Curiously his first taste of the effects-driven spectacle that would typify his later films came in as a way of fleshing out his documentaries. One sequence of his 1956 film The Animal World, on dinosaurs, featured effects by the great Ray Harryhausen, and his very next film was his first all-star extravaganza, the cameo-packed The Story of Mankind.

In 1961, Allen made Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, the dry run for the formula that he would turn into such success in the 1970s – disaster, torrid human affairs, washed-out actors like Peter Lorre rubbing elbows with awkward teenyboppers like Frankie Avalon – but the film's financial success paradoxically pushed him temporarily away from movies. Starting in 1964, Allen turned into a TV impresario, adapting Voyage into a four-season TV show, and subsequently overseeing the creation of cheerfully hokey genre fare like The Time Tunnel and Lost in Space, the latter pioneering the use of that low-budget effect where shaking a camera would look like a stationary space ship set being tossed back and forth.

Allen's reputation, however, lies on the pair of disaster epics he produced in the first half of the 1970s: The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974). Both were enormous hits, and the latter even managed to nab a Best Picture nomination over films including A Woman Under the Influence and Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore. In both cases, we watch as a hugely luxurious engineering marvel (a giant ocean liner; the tallest skyscraper in the world, cleverly built in San Francisco) plays host to a seemingly endless parade of famous faces, before a freak accident turns it into a death trap where everybody has to avoid jets of flame and jump over torn pieces of metal to escape.

When you have a shtick that works, you use it.

The Towering Inferno (1974)

The Towering Inferno (1974)

They're not good films, of course; in fact, they're downright trashy. I am myself somewhat more partial to The Poseidon Adventure, which feels less like a cartoon and has more plausible action sequences (directed by Allen himself, without credit), though The Towering Inferno has the more star-studded cast. These are films with stories based on outlandish scenarios, characters who never earn more than a single adjective worth of personality, and an overwhelming tackiness in design and attitude that out-'70s the '70s.

But they are so very delightful as they bob along! Watching ace actors like Gene Hackman and Shelley Winters (in Poseidon) or Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Faye Dunaway, and Oscar-nominated Fred Astaire (in Inferno) offers the expected campy pleasures, but it's not just hokiness that the films have to offer. This is passionately overstuffed spectacle done at a time when it took real planning and care to make something this mindlessly explosive. The modern blockbuster age has spoiled us for the deep-set sincerity of an Irwin Allen effects setpiece; when he has idiots put themselves in the way of a falling girder, there's a sense of joyful discovery that still gives the scenes a kick even if you can watch better action with more nuanced characters every night of the week on network television.

The Poseidon Adventure (1972)

The Poseidon Adventure (1972)

The shocking thing about Allen's triumphant ascendancy to the level of super-producer on the back of those two hits is how short his stay was at the top. He followed The Towering Inferno with a return to directing in 1978, making the killer bee movie The Swarm, with a stacked cast of its own (Michael Caine! Katharine Ross! Lee Grant! Olivia de Havilland and Henry Fonda thoroughly embarrassing themselves!), and the worst script he'd ever sign off on. It's a baffling mixture of hysteria and confusing exposition, more of a tawdry '50s B-movie than a spectacular effects orgasm, and it's long – the two-hour theatrical cut is dismal enough, but the directors' cut adds forty minutes that turn it into an outright dirge. Allen's last theatrical release tried to return to past glories: it's a sequel to The Poseidon Adventure, a film that would seem to have blocked off any avenues for continuing its story. But 1979's Beyond the Poseidon Adventure grimly finds a way, bringing Caine in alongside Karl Malden and Sally Field (in the same year she won her Oscar for Norma Rae, no less!) to re-tread the beats of the original film, with a tacked-on terrorist subplot. It's hopeless, though there's spunk to it that The Swarm lacks.

The Swarm (1978)

The Swarm (1978)

Even if the heart of legacy consists of just two films and a TV series, Allen's work continues to echo, every time a filmmaker decides to make a buck or two million by blowing something up and cutting to a famous person grimacing in dismay. The Allen formula has its descendants in everything from Independence Day to Impendence Day: Resurgence, due out this very month. 25 years after his death, Allen's lesson that audiences will flock to the peculiar marriage of soppy melodrama and mindless destruction will pay off; the pity is that so few of them have had his gusto, commitment, and mushy sincerity.