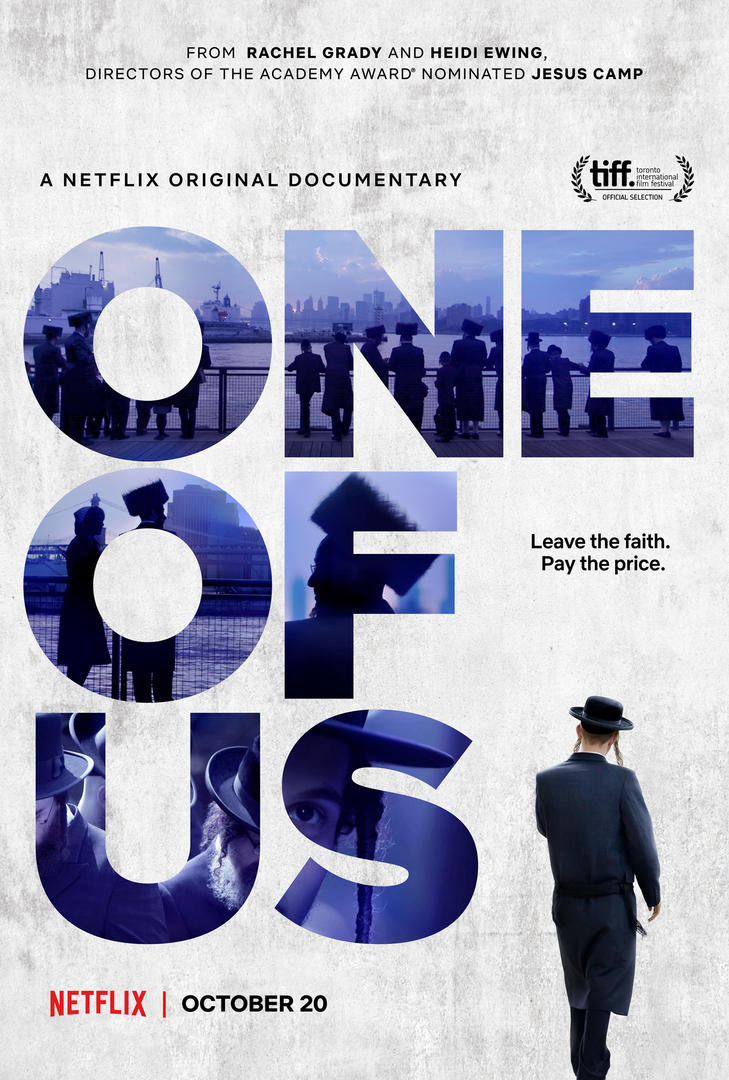

Not content to let scientology corner the market in controversial religion exposes, directors Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady focus their attention on New York’s Hasidic community in their latest feature. A dramatic change of pace after last year’s celebrity bio-doc Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You, the filmmakers return at least somewhat to the themes of their most famous film, the Oscar-nominated Jesus Camp. Yet despite the potential cross-over to be found in the pair that seek to uncover the alarming practises of organised religion, One of Us is a much different beast.

Unlike that earlier film, which trained its cameras on the inner-circle of a camp for raising the next generation of evangelicals, One of Us observes from the outside, following the stories of three individuals who have attempted to extract themselves from the community and tell some often haunting and traumatic tales of their times within it...

Unlike the fundamentalist Christian world of Jesus Camp, or scientology as seen in film and TV by Alex Gibney, Louis Theroux and Leah Remini, most viewers’ concept of Hasidic Judaism is not one of cult-like behaviour and dangerous propaganda. That makes the central narrative drive of One of Us an initially rather interesting entry point. Opening with an alarming 911 phone call of a woman who we learn to know as Etty, Ewing and Grady immediately place us on edge. It’s a dramatic way to begin the film and to enter us into the world Etty, a woman who fled her abusive husband and the Hasidic community with her children.

But we soon cut to two other subjects: Luzar, a budding actor who left his wife and kids behind to move to Los Angeles, and Ari, a young man with substance abuse issues and a story of assault from within the community. Unlike Etty, who has joined a support group for those who have extricated themselves, both Luzar and Ari waver on their commitment to leaving the community. This juxtaposition ought to give One of Us a particularly refreshing multi-sided view of the story, but why Ewing and Grady chose to end the stories where they did ultimately makes for an unclear and confusing portrait. So much remains unresolved that when coupled with an inability to delve into the interior world of the Hasidic community makes for an unfinished, unsatisfying film.

Most frustratingly of all, however, is the documentary’s visual style. Ewing, Grady and their cinematographers Jenni Morello and Alex Takats adopt a truly nauseating aesthetic whereby almost all of the film is framed as if the camera is covertly hiding behind the metaphorical bushes. It makes sense at times, particularly as Etty spends the early portions of the film disguised and unwanting to show her face, but eventually the entire film adopts this look. Ordinary sequences are filmed by a verite-leaning camera bobbing behind buildings, objects and people. Half of One of Us’s screentime is spent out of focus with large swathes of negative space. It’s perhaps irrational, but it’s nonetheless a distraction that makes the trauma of its subjects even harder to penetrate.

Comparatively, Alex Lora and Antonio Tibaldi’s Thy Father’s Chair is far simpler yet overwhelmingly for satisfying. This time focusing on the Orthodox Jewish community, in particular two identical twin brothers, Avraham and Shraga, whose home in Brooklyn is filthy, riddled with bed bugs, and overstuffed with furniture and clutter. Playing out like an episode of Hoarders meets Grey Gardens, Thy Father’s Chair is brisk (a refreshing 74 minutes) and often highly entertaining glimpse into the lives of two men who find themselves forced to confront a life of stockpiling useless objects and paraphernalia.

While the film is often funny in its absurdity, it is never cruel, which is the most important factor to its success. By the end it offers very real pathos as we gain greater insight into the brothers as two lonely, tortured men who struggle for any sort of connection. So much so that they appear desperate to befriend the cleaning men who have descended upon their home. The camera never leaves the premises, allowing us not just a glimpse of their garbage-strewn world, but a real sense of the isolation that these brothers must deal with day in and day out. And as their junk is has been hauled away, Thy Father’s Chair transcends its initially simply premise and becomes something much bigger with things to say about the world and how it can so easily leave people behind in a wreck of their own making.

Release: One of Us is streaming on Netflix now. Thy Father's Chair is now playing in NYC and LA.

Oscar Chances: Netflix have bigger fish to fry, but Ewing and Grady's names are not to be underestimated. Thy Father's Chair is not the sort that they have ever gone for.