By Jose Solís.

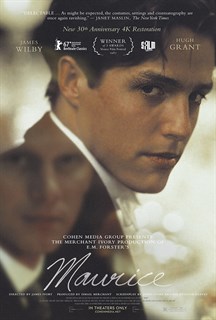

Can you believe Maurice came out 30 years ago? James Ivory’s film adaptation of E.M. Forster’s novel was released in the fall of 1987, a year after the Oscar winning A Room with a View. While it was never as celebrated as the former, throughout the years it’s come to be more highly regarded for its groundbreaking LGBTQ romance, and as the film that launched Hugh Grant’s screen career.

The tale of forbidden love between the title character (played by James Wilby) and a male servant (Rupert Graves) is filled with pithy dialogue, handsome actors and a then unparalleled sensuality when it comes to conveying gay romance. Its influence can be seen in countless films that came after it, yet for decades it remained the happiest of LGBTQ screen romances. That's a position I discussed with Mr. Ivory as the film is being re-released in theaters this weekend in a 4K restoration to celebrate its landmark anniversary. (If you're in NYC it's showing at the newly renovated Quad Cinema which has its own rich history of showing LGBTQ cinema).

Our interview follows:

JOSE: You’ve mentioned you enjoy watching your films...

JAMES IVORY: I enjoy watching them on the big screen, let me put it that way. What I like to do is see them big, especially after I haven’t seen them in a while.

JOSE: Have you re-discovered anything about Maurice having seen it recently?...

JAMES IVORY: I can’t really say because Maurice is one of the films I have been able to see fairly frequently. It’s shown quite a bit, and I hadn’t forgotten what it was like, or failed to remember it. Maybe as we keep talking I’ll be able to answer this better, I liked it, I do like it, it’s an appealing film, so you know maybe as we talk you’ll shake something loose in my head (laughs).

JOSE: I admire the way in which your films touch on class, which is something most American films stay away from. Writing the screenplay, did you see Maurice’s main conflict being more about falling in love with someone of a lower class or embracing his homossexuality?

JAMES IVORY: It was about both. In the first place, all of Forster's novels and his writing have been about the English class system, which luckily we don’t have, we can escape the American class system easier than they can, it’s not as ingrained. If you were to make a film about a Forster novel, it would be about the class system because it’s a big issue in his work, it can be understood or heard in every line the characters speak, if they’re English. It was also an issue in Maurice’s mind when he began his affair with Clive’s servant, that was considered “letting the side down”, the side being the upper middle class or upper class. Clive and Maurice weren’t aristocrats, they were upper middle class, but in having an affair with a servant class was an issue for him. At the point he’s afraid of being blackmailed by Scudder he seems aware of the problem that kind of affair would bring him, but then he doesn’t care anymore, he throws that out, he comes to his senses.

Do you feel the class element has been lacking from modern gay romances?

I wouldn’t say that, even in this country which we like to say is classless, that’s a fake idea. We have our classes, but it’s about being rich or poor, rather than your hereditary place in the class system. Class is part of popular romance, the rich man falls in love with a poor girl, we’ve had that over centuries and all over the world, that’s part of our stories too, it’s part of Hollywood.

Rupert Graves mentioned wanting to do the film because he wasn’t satisfied with his performance in A Room with a View. Did he talk to you about how to improve?

The only thing he said was he was happy to play Scudder because he had never played a working class guy before, he’d only played posh types. He first came to people’s notice when he did Another Country onstage and he played one of the schoolboys in a fancy school.

Scudder’s trip to Argentina never happens, but did you imagine a scenario where he did? What would his life had been like there?

I didn’t really think about it because I didn’t know anything about Argentina in those days, now having made a film in Argentina I understand what happened to people who came there from all over the world. Lots of English people immigrated to Argentina, Germans too, and people from all over, it was an up and coming country. They did very well in the American sense of the idea, they started companies and rose in class until they were no longer poor. Argentina became a very rich country, like the US it’s entirely populated by descendants of immigrants who arrived at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. There are many Italians in Argentina, also many Jewish people, I was told Buenos Aires is the second biggest Jewish city in the world after NYC. That’s what would’ve happened if Scudder had gone there.

However, I imagined his life when he stayed with Maurice. The Great War was a few years away and what happened to those three young men in 1914 would’ve been, Clive, who was of the officer class would’ve immediately become an officer and gone to France where he probably would’ve been killed. Maurice was also of the officer class but he would become a conscientious objector and stayed behind, but Alec would’ve enlisted. They would survive the war and pick up their lives after it was over. That’s the future I imagined for those three.

Every time I watch Maurice it’s so hard for me to believe it’s actually a gay romance with a happy ending. When you were working on it, I don’t believe there were many films with happy endings.

There weren’t. There were some even in Forster’s day though, there were gay relationships that succeeded, although there were none in fiction. That was one of the reasons Forster never published the book in his lifetime, homosexual acts were a crime and if he’d published the novel with homosexual acts in which these criminals had a happy ending, he thought he’d be arrested for obscenity. He also always insisted the novel had to have a happy ending. It’s interesting because very often, even today, when you find a gay male couple they’re of different classes, one will be an educated middle class man, and the partner is working class.

I like how Maurice and Todd Haynes’ Carol make for such an interesting duo, we see the same dynamic in terms of class, the optimistic ending, and even something as obvious as an upper class blond falling for a working class brunette.

(Laughs) There wasn’t that big a gap between those women really and it was an American story, our class consciousness isn’t as strong.

Were you surprised not to see happy gay romances even after you made Maurice? I don’t think we had that many until Carol and Moonlight.

No there weren’t! An example of where there might’ve been one was Brokeback Mountain, but both men are punished, one is killed, so you’re right, in Moonlight we have a happy ending we believe.

You’ve said it wasn’t hard for you to make Maurice despite the gay plot, so were you hopeful about it starting a change in how films perceived gay men?

I wanted to make the film because it was the other side of the coin of A Room with a View, in both stories, both young people are lying to themselves about who they really love and what life should be. They’re modeled for social reasons, so they were mirror images in reverse, one male, one female. When I re-read Maurice, after not thinking about it for a decade, I felt it was very similar to A Room with a View, they’re about people who don’t understand their feelings and are unhappy. I thought it would be good to show that, in fact that situation is very much still in existence today right here in our own country, there are many people who are gay but it’s hard for them to accept it and act upon it. It’s less of a problem but it exists in modern life.

One of the most beautiful things in the film is when Scudder asks Maurice to call him by his first name, there is something so intimate about this moment and it made me wonder if you had been thinking about Maurice when you wrote the screenplay for Call Me By Your Name?

Not really, they’re very different kinds of stories, in different countries and in different times. There was no great set of principles inhibiting either of the young men from acting on their desires, there was no fear of what society would say, they were afraid of rejection, which is a universal reaction.

Was there a specific reason why you didn’t direct the film as well?

The French financiers didn’t want two directors, maybe they didn’t like the idea of having to pay two directors. I never asked that question though, but it’s in the background, maybe they thought it was too expensive. I’ve never co-directed anything and I would’ve had to get the permission from the Directors Guild, they don’t like to give permissions for that, probably because so many of the scenes were in Italian they might’ve given me a waiver, but I think it was a financial thing. Producers were afraid that it might slow things down, they wouldn’t be able to work so fast if they had two directors talking about how to do something. I would think like that if I were producing a film with two directors who have never worked together and who might fight over certain things.

James Ivory during the 'Maurice' production.You focused more on directing, but also wrote several screenplays, did you grow to like screenwriting more?

James Ivory during the 'Maurice' production.You focused more on directing, but also wrote several screenplays, did you grow to like screenwriting more?

Not necessarily, that’s my sixth or seventh produced screenplay, I’ve co-written original screenplays and adaptations. I’m mostly a film director though, whether I was going to direct the film or not, I wanted to have my own screenplay so I could develop the story in my own ways. As a director you want to do things in a particular way and I wanted to set that up for myself. I might write another screenplay though, that’s not impossible.

Were there any scenes from Maurice that you shot and loved but could never find place for in the final cut?

The film had a very different form in the screenplay, in editing it became a straight narrative. In the screenplay a lot of the story was treated as a flashback, so we ended with many scenes we had no room for. A lot of those scenes were in the Criterion DVD, I don’t know whether the new DVD being made by Cohen Media will include them. I imagine they will also be there.

What’s the one thing you focus on the most when you’re supervising the restoration of one of your films?

The color. I go where they are transferring it and I want to see the color in terms of light and darkness, most of my cameramen are unavailable, some have died, some are far away and can’t come, so I have to do that. I know what it should be and I tell them, “don’t you think this is a bit yellow?” and they correct it.

Many people assume that adaptations or period pieces made by modern directors aren’t personal, watching your films it’s clear that’s not true. Which of your adaptations was the most personal to you?

A lot of them were very personal, I disagree with the idea that adaptations can’t be personal, the novels they’re based on were clearly very personal to the author, as well as the thousands of readers who are affected when they read them. It’s the same for a director, you personally respond to a story someone wrote, you like the characters, the story and there may be something in the story that appeals to you deep down and you’re not even aware of it. That has happened to me sometimes, I see scenes of my old movies and go “so that’s what I was thinking about that then”. Whoever says they can’t be personal don’t know what they’re talking about.

Maurice is back in theaters tomorrow in select cities.