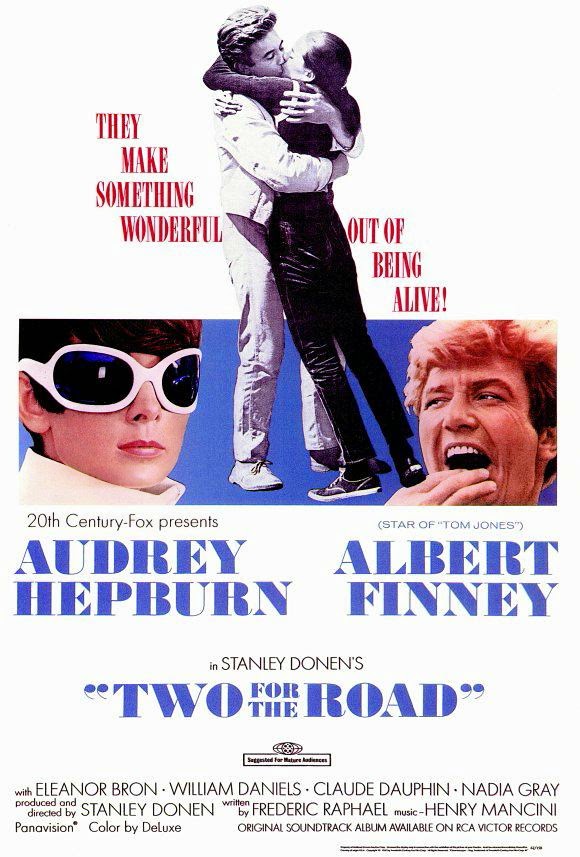

Tim here. This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of one of the tiny gems in the careers of Audrey Hepburn, Albert Finney, and director Stanley Donen: Two for the Road. It's a British film that picked up a handful of important awards nominations – writer Frederic Raphael at both the Oscars and BAFTAS, Hepburn at the Golden Globes, Donen with the DGA – and went on to be largely overlooked in the following five decades.

Tim here. This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of one of the tiny gems in the careers of Audrey Hepburn, Albert Finney, and director Stanley Donen: Two for the Road. It's a British film that picked up a handful of important awards nominations – writer Frederic Raphael at both the Oscars and BAFTAS, Hepburn at the Golden Globes, Donen with the DGA – and went on to be largely overlooked in the following five decades.

That's understandable; it's not a film primed to appeal to the fandom that it seems like it should have. Donen in the director's seat and Hepburn as the top-billed lead both suggest certain kinds of films, if not necessarily the same kind of film: bubbly comedies in his case, elegant Continental romances in hers (splitting the difference, four years earlier they collaborated on Charade, a bubbly Continental comedy). Two for the Road isn't devoid of humor, but it's not primarily a comedy. Instead, it's a serious depiction of a marriage of some ten years or more, long enough for comfortable familiarity to have settled into tetchy boredom.

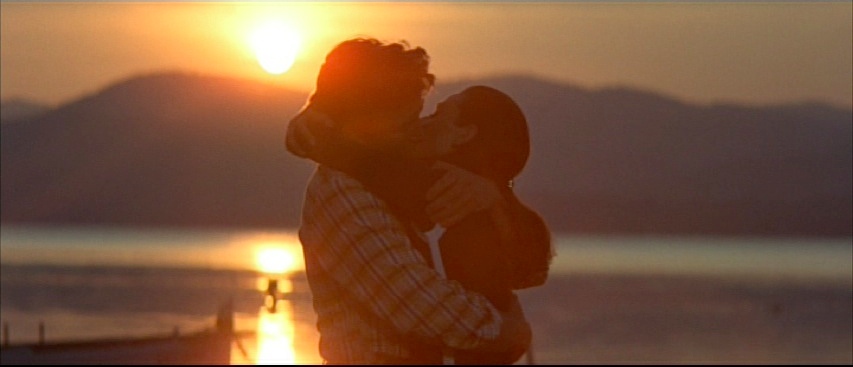

The rather showy structure of Raphael's screenplay presents the life of the Wallaces, Jo and Mark, as a series of flashbacks all set during various trips they've spent driving along picturesque French roads. The film contrasts their initial meeting and courtship, their time as newlyweds, and the encroaching sullenness between them as the years go by, with this last trip, spent in polite misery as they both consider the possibility that they're trapped in a relationship that has exhausted itself. It's smart without being too challenging for what is still, after all, an Audrey Hepburn picture directed by Stanley Donen, but even more than the ingenuity of the script, what drives the film is its shockingly unsentimental portrait of a marriage in decline. This was 1967: using the language of romantic comedy to explore the pain of marriage was simply not done.

Fifty years haven't done much to blunt the basic shocking honesty at the film's heart: if it looks like a sleek '60s European romp, one tends to expect that it will act like one. It's not that Two for the Road is some kind of stark, psychologically realist plunge into the darkness of a failed marriage; it's still a predominately uplifting film, at least as anxious to show us the strong love that once grew between Jo and Mark as the slow dissolve of that love. It still has handsome cinematography of the French countryside, and Hepburn wearing '60s chic (and sometimes amusingly dated) costumes.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the film is that, on paper, Finney is the one who doesn't fit in with all the rest: the light directorial touch, the glamor, the beautiful Henry Mancini score (for which he too received a Globe nomination), the fact that Mark is a wealthy architect for members of the French elite. None of this seems to quite square with the loutish "angry young man" type that Finney had honed in his compact film career and somewhat more established stage career to that point. And yet it's exactly Finney's presence that seems to control Two for the Road: the film feels more of a piece with the stern kitchen sink dramas that actors of Finney's generation had begun to push into the mainstream of British cinema. The quiet note of disappointment that first enters the Wallace's marriage does so through Mark's low-key cynicism, and it's Finney's ability to embody a certain tough, tense frustration that makes that cynicism so believable.

Whatever generated it, the film's commitment to this strain of realism energizes most of the people involved in making it. Hepburn was rarely better than here, playing a flesh and blood woman of some petulance, disappointment, and encroaching middle-aged boredom, rather than the idealized concepts she frequently got saddled with, and thriving under such conditions (the idea of a genuinely prickly Audrey Hepburn is almost impossible to visualize, until you see it here).

Donen's directing, if not as fluid as in his wonderful musical collaborations with Gene Kelly in the decade prior, has a lightness of touch that can shade into melancholy, but never turns this generally serious move into a deeply sober account of personal crisis.

Which is not to say that deeply sober films are bad, and if there's one real complaint I could make about Two for the Road, it's that it's a bit glossy and smooth, for something dealing with such deep set human feelings. It's still a Stanley Donen film shot in some of the loveliest corners of France, and quite satisfying on that level; but we're not talking Scenes from a Marriage, and for all the low-key hurt on display, it never truly seems like this marriage might actually be in mortal jeopardy. But then, I don't suppose it needs that to make its point: life with a person you love most of the time can still be damn hard. The terrific performances of Hepburn and Finney do an admirable job of exploring that idea with rich chemistry and combative tension, and the humane wisdom of Two for the Road is more than deserving of rediscovery. A half-century old or not, this still gets at something hard and true.