by Jorge Molina

Episode 8: “Creator/ Destroyer”

Though the penultimate episode is a deeper origin story for Andrew, we open again a Versace vignette: their only appearance in the episode. But this one does not feature Edgar Ramirez, or Penelope Cruz. We see Gianni as a young boy in Italy, developing a passion for dressmaking. His mother is supportive enough to not only understand this passion, but fosters it. “You can do whatever you want in life, but you have to work for it.” Despite his classmates’ teasing and the repression of other adults, Gianni takes on the craft from his mother.

The show continues to make thematic connections between Andrew Cunanan and Gianni Versace, implying that their life paths and goals were remarkably similar. They are both immigrant stories chasing the American Dream against a system and a society that constantly looks down upon and underestimates them. They are two different sides of the same coin. I think the show is oversimplifying a much more complex issue and boiling it down to thematic parallels, but it is effective in the context of a somewhat fictional miniseries...

We then go to 1980s San Diego, to Andrew’s childhood. His family is moving into an up-and-coming neighborhood. His three older siblings and his mother are helping with the furniture, while Andrew reads a fashion magazine. We quickly see that he is given overt and outlandish special treatment by his father Modesto (played by Jon Jon Briones, in a remarkable one-episode showcase). Modesto has placed his dreams and ideals of success into Andrew: he is special, he deserves only the best, and the world owes it to him.

It is here where we see the origin of Andrew’s delusion about what he thinks his life should be, and his inextinguishable desire to attain the unattainable. It’s all he ever learned from his father. He was given the master bedroom while his other siblings had to share a single room. His father buys him a car before he is old enough to drive. He inherits this entitlement just as he would inherit the cycle of abuse toward his mother.

We can also trace Andrew’s magnetic charisma and talent of spinning lies into entrancing stories back to Modesto. There is another sequence that juxtaposes two interviews, replicating the device in episode five, where Versace’s coming out profile in The Advocate was paired with Jeff Trail’s CBS piece about the military. Andrew applies for the best private school in the state while his father applies for a job at Merrill-Lynch. Modesto sells his life story as the ultimate American Dream narrative: he was born in the Philippines, joined the U.S. army in hopes of moving there, and took himself and his family from poverty into one of the best neighborhoods. He sells himself as a success story, just like Andrew will do countless time in the future. The firm buys it, and hires him.

Andrew is also accepted into the school. But he is aware of the enormous pressure that this means for him and his family. His father only sees him in terms of potential, of how much money he will be able to earn, and what he will be able to achieve.

As his father is putting Andrew to bed, the series heavily implies that he constantly molested him, and that his favoritism and endearment for him had much deeper roots, and consequences. There is no real-life evidence that supports this claim that the show makes. It's something that makes narrative sense and adds a layer of complexity to Andrew’s actions, but at the same time feels like an effort to justify them. Villains are scarier when we can’t understand them, and the show continues to make an effort to make us try to empathize with him.

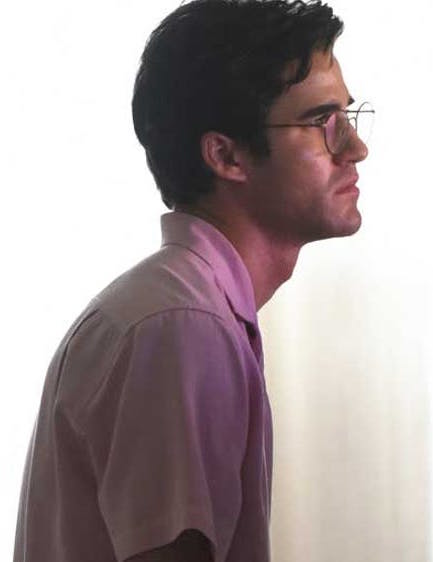

We catch up with Andrew in high school. He is much closer to the charisma machine that we’ve come to know all these episodes. He’s fully in charge of the image he projects, not caring if the appears flamboyant, queer, or different. He’s just interested in appearing at all.

He has been keeping a secret relationship with an older man, that he desperately wants to make public. He dumps Andrew when he tries to take him to a high school party, which Andrew decides to attend on his own. As he walks through the sea of judgmental teenagers, he takes control of the dancefloor in the most head-turning red leather jumpsuit, fully aware that every glance in the room is upon him.

Feeling bad for him, Lizzie (the delightful Annaleigh Ashford returns again) joins him to try and save him. We see them striking up a real connection, until she has to confess that she is in fact a married woman who has tasked to chaperone this party. In a way, they are both putting up fronts. Andrew is intrigued with her. And what was perhaps his only true friendship starts then.

If the show has made something clear over and over, is that anything that flies too close to the sun will eventually crash and burn. The life that Modesto has made for himself and his family will crumble. He had been engaging in fraudulent stock investments for years. The police are now after him. In a matter of hours, he leaves his job and his family behind, running away to the Philippines.

Andrew refuses to believe that his father, this omniscient figure that has become the moral guiding light for every action that he has done or will do, would abandon them like that, with no plan. So he chases him down to the Philippines, and finds him hiding in the shed of an uncle he’s never met.

This final confrontation between Andrew and his father puts together all the themes of the show in a superbly acted showcase for both performers. It’s about immigrant sacrifice, it’s about the faults and privileges of the American Dream, it’s about abandoning your identity in pursuit of a better one, it’s about not being able to escape who you are and where you come from. It all escalates to a physical confrontation, in which Modesto dares Andrew to kill him, taunting him that he is not “man enough” to do it. Knowing that their relationship is now broken forever, Andrew returns to the U.S. He distances himself from his father, not realizing that he will still carry on everything he taught him for the rest of his life. He could not kill him.

In the last scene, Andrew applies for the job at the pharmacy that we saw him miserably working at the start of the last episode. When the manager asks him what his father does, Andrew tells him he owns pineapple plantations in the Philippines, shedding him from his life, but effectively becoming him, as well.

While last week’s episode felt satisfying in that it neatly tied all the plot points that we’ve seen through the show together, this week felt emotionally satisfying in offering a deeper look into Andrew’s psychology and motivations. The show’s tendency to portray him a victim of circumstance rather than someone fully accountable is questionable. But, as a character study, this is nevertheless an episode with plenty of nuance and outstanding moments.

Episode 9: “Alone”

On the season finale for the show, Andrew’s life finally gets to a crossroads that for once he can’t charm, con or murder his way out of. As we focus on the final day of his life, with the cops slowly encircling him until he decided to take his own life, we also see the lasting effects that his actions had on every character that he came across; and how he was left to die, as the title indicates, all alone.

The episode opens with Gianni Versace’s assassination. After eight previous backtracking episodes, we now understand the emotional baggage that led Andrew to the steps of that mansion, and suddenly that scene (which also opened the series), is charged with deeper meaning.

Andrew savors his “victory” for a few hours before his dire reality sets in. He struts around the city with a proud smirk on his face; he treats himself to a bottle of champagne. He then watches on TV that the police have successfully identified him, and for a moment, is also proud of that. But he now needs to be on the move.

He tries to leave Florida, but there’s a police checkpoint on every exit out of Miami Beach. In a first display of the desperation that would stick with him from then until his very end, he screams under a bridge, trapped and realizing he is being cornered. He stays at an empty boat for some time, and eventually breaks into a house that would become the place of his death.

From the moment he sees his face on television, to the final pull of the trigger, images of every person whose life he forever changed appear both to him and in separate scattered scenes for the audience. For him they are the ghosts of his past coming back to haunt him. For us, they are reminders that even though we’ve been watching mostly fractured, episodic and self-contained parts of this story, it’s all one whole narrative, where one action led to the next and its consequences rippled throughout.

We get the triumphant return of Judith Light as Marilyn Miglin. The FBI has tracked her down to Tampa to let her know that the man who killed Versace is also the main suspect in her husband’s murder. She is outraged at how the police is only starting to act now that a famous person was involved, even if they’ve had Andrew’s information for months.

This is a sentiment that has been brought up since the first episode through the various depictions of police negligence and incompetence, and it’s brought up again when Ronnie (Max Greenfield) is taken into custody and accused of protecting Andrew. Yes, they talked about Versace together, he says. All the time. They fantasized about having his life, about not being constantly overlooked and tossed to a corner.

The ghosts of his actions also appear to Andrew in the confinement he has created for himself. He catches Marilyn’s appearance in the Shopping Network, where she delivers yet another impassioned speech about creating a perfume for her mother. As she says this, we see the police barge into Andrew’s own mother’s house; another relationship he has destroyed.

Pictures of Jeff Trail and David Madson appear on television, in what is basically now a 24-hour news cycle coverage of the manhunt for Andrew. This is the only mention or appearance we get from them. This speaks to the act of turning victims of a serial killer into mere statistics, which the show actively tried to contradict by showing us their backstories. The fact that this is all the screen time they get makes this even more resonant; we know the people that they were.

Weaved through the episode it’s the Versace family dealing with Gianni’s sudden loss. Donatella and Antonio are two other people (along with Marilyn Miglin, and even his own mother) whose life Andrew indirectly and forever changed by the murders.

We see Antonio’s deep mourning and pain over the loss of his life partner, and Donatella’s steel front against it all. She needs to keep her composure, and take the reins of the company, like her brother pushed her to. We also see how the family dynamic is irreparably broken. Without Gianni, Donatella and Antonio have nothing to offer each other. Donatella goes as far as to refuse to let him stay in one of the Versace houses. “I’m sorry for your loss,” she tells him, as if they both had lost different people.

Andrew watches Versace’s funeral on television. The more time he spends trapped in this house, and with himself, the more confined the spaces feel, the sweatier he is, the more claustrophobic and suffocating the filmmaking became. Andrew takes in the grief of the packed cathedral, and grieves himself. He also watches Liz Cote give an on-air testimony about still caring for him, knowing that what he cares most is what other people think of him. Liz truly was the only person in Andrew’s life who ever made a true connection with him.

So then Andrew turns to his father for comfort. The man he tried so hard to deny and let go of on the last episode, but that eventually molded him into the man he became. He calls him in the Philippines, begging for help and rescue. Modesto says that he will be there immediately, charges against him be damned. He tells Andrew to be ready. He has a plan, the plan Andrew always knew and wished he had.

But then Modesto appears on Andrew’s television, bragging about the way he raised him, sharing intimate details about his childhood, saying that he will sell Andrew’s life rights to Hollywood (an ironic statement in a series made about him). He’s clearly not coming. In another display of rage and desperation, Andrew shoots the TV, right at his father image; finally killing him in his mind. Perhaps too little too late.

The police finally catch up to Andrew’s whereabouts. In a matter of hours, he is surrounded and out of options; out of places to hide, people to run towards, lies to tell. He heads to the bedroom, where he encounters the last person whose life he destroyed: his younger self. Both Andrews watch TV together, the young boy amazed and entranced at the coverage he is getting.

Andrew then shoots himself, after one last look in the mirror at the man he became. Immediately after pulling the trigger, we cut back to the opera sequence with Versace, all the way back from the premiere episode. In what now seems confirmed to be a fantasy scenario, Gianni and Andrew have one final conversation. Andrew admits that this (what was perhaps the pinnacle of his ideals: Versace’s life, feeling wanted and successful and accomplished) actually feels like hell.

The last sequence of the series is not of Andrew, but rather of how the survivors of this story are left to deal with the wreckage that Andrew left behind. Antonio has seemingly lost any will to live without his lover. Marilyn Miglin keeps slowly unveiling a whole new side of her husband’s life that was unknown to her. And Donatella, away from the funeral and the cameras and the business obligations, finally allows herself to grieve, and breaks down. These people had everything ripped away from them. The man responsible is dead. How to move on from here?

While this series was very much Andrew’s story, his actions had long-lasting consequences way past the murders and his own suicide.

The show is now over. I may need some time to fully sit with it as it was not an easy watch. It was a raw and often uncomfortable look at difficult issues that are still widely relevant inside the gay community, shown through the lens of a serial killer.

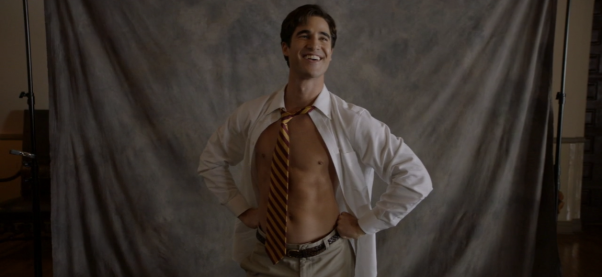

But I do think we will look back at it as a powerful piece of queer art. Its performances are incredible, especially Darren Criss’s, doing the best work of his career. The series was not at all the kitschy, soapy crime drama that was advertised. It was a necessary and beautifully crafted deep dive into a subculture of society that is never represented with such honesty, willing to portray the ugly side as brightly as what makes it soar. It wasn’t O.J., and perhaps it was a mistake to expect that. Versace is its own thing: ethereal, painful, a strange and unsettling product of beauty.