John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#16 — Mary Fisher, a frivolous romance novelist who steals the husband of a dowdy housewife.

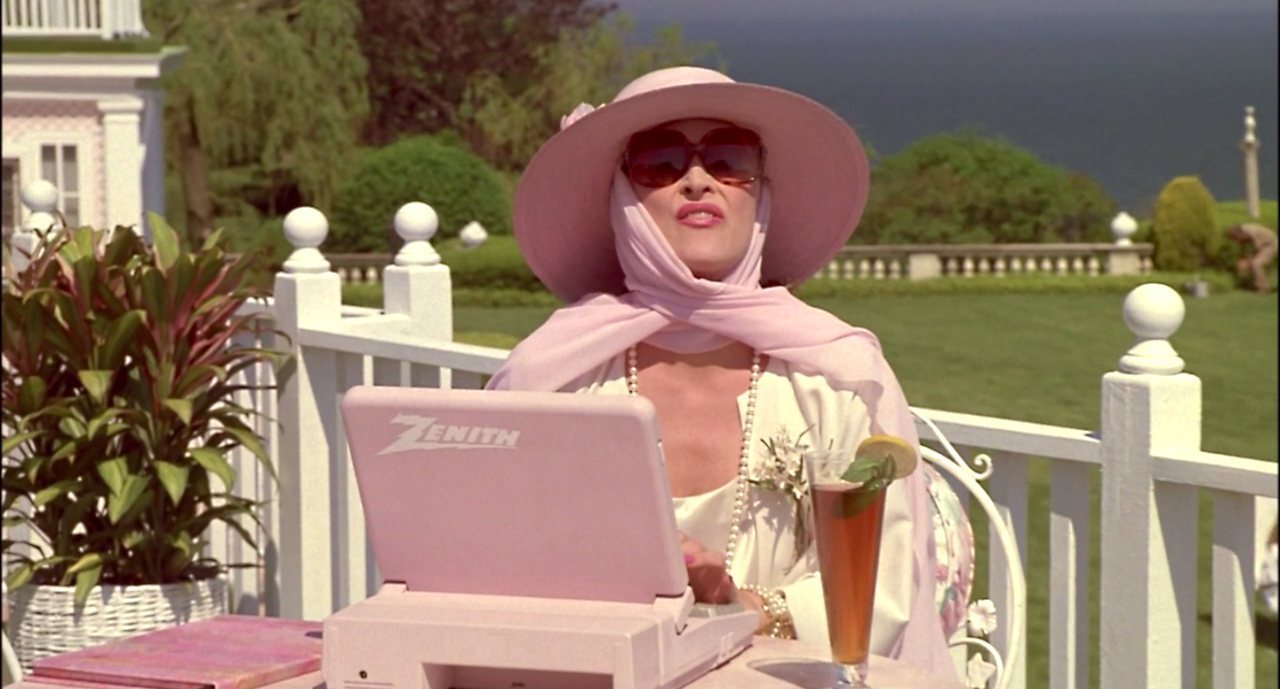

JOHN: For such a tepid and unruly film, She-Devil enjoys quite an outsized reputation. Considered by many to be the nadir of Streep’s early career and one of her worst performances, She-Devil is also a Streep turn that is often reblogged context-free online, which makes sense when one considers its outre, GIF-ready moments of ironic femininity and gaudy Real Housewives of Long Island aesthetic that some might consider ahead of its time. Having seen these images of Streep’s Mary Fisher before watching the film, I had anticipated fun kitsch or perhaps even smart camp. Roseanne’s film debut! Susan Seidelman with a budget! Meryl’s comedy vehicle to silence the critics! But these are promises that She-Devil most certainly does not keep...

We receive, instead, a half-baked revenge tale whereby Roseanne’s unattractive and incompetent housewife, Ruth Patchett, enacts vengeance on Streep’s self-possessed romance novelist after she steals her handsome and successful husband Bob (Ed Begley, Jr.). A “black” “comedy” sans any insight or edge, She-Devil is, most surprisingly, no fun.

Streep is Mary Fisher, an affected and ostentatious romance novelist who lives in a hot pink mansion bedecked with a heart-shaped bed, a small white dog, an indoor olympic pool, and her very own live-in Latino butler and boytoy. Mary speaks in a posh, breathy voice that Streep finds somewhere in the back of her throat, hitting high notes of exasperation and astonishment as if she had just run a marathon. “That’s your wife? That’s too bad,” she coos at Bob after Ruth clumsily spills a drink on her pageant-pink dress at a Guggenheim function. She invites Bob in for a nightcap and he proceeds to compliment Mary on her estate and literature. “I try to think... only beautiful thoughts,” Mary demures, before finally seducing him with the line, “I do a lot of... research.” In these introductory scenes, I was rather astonished at how dissimilar Mary Fisher is to almost all of Streep’s past performances, but I couldn’t place my finger on what exactly sets Mary apart. As the film progresses — or, rather, plods to completion — it becomes clear that Streep is not at all interested in digging deeper or revealing sides of Mary that aren’t apparent from the very first glimpse of the performance. For an actress whose raison d’être is illuminating and prismatic performances of conflicted women, Mary Fisher stands out as a rare one-note, even heartless take on an inherently exasperating character. This may be my first time watching a Streep performance and sensing that she actively dislikes the character she is playing.

Let’s backtrack: She-Devil is not high drama nor middlebrow docudrama nor a dramedy; it’s outright satire, which requires marked differences in performance style. Streep’s penchant for realism and lived-in characterizations would have been entirely misplaced in this implausible movie. But even conceding that satire doesn’t require naturalism, Streep’s performance in She-Devil remains cruel and pitiless, as Mary Fisher quickly becomes (one of) the film’s titular devils, an obstinate gag of a character that remains largely untouched by Ruth’s “empowering” female rebellion. In committing herself to surface-level jokes and protracted line readings, Streep turns in one of her most boring and tired performances. I blame the script, and the frankly pedestrian direction, on squandering most of the goodwill in its cast and set-up.

Streep, Roseanne, Sylvia Miles, Susan Seidelman, and Linda Hunt on the set of "She-Devil"

Streep, Roseanne, Sylvia Miles, Susan Seidelman, and Linda Hunt on the set of "She-Devil"

But Streep herself is oddly unconvincing. I kept waiting for her impeccable comic timing and imagination to enliven this static character. In terms of pure comic hijinks, Streep is outmatched by Sylvia Miles, playing her brash and impudent mother, and Linda Hunt, playing Ruth’s nurse coworker and partner-in-crime, who is doing the least for her handful of laughs. Even when Streep earns a laugh (like in her best moment, when she uses the foam of her swimming pool to shield her naked body from Ruth’s children), the performance rings rather hollow.

Did you laugh at Mary Fisher? Or did you just catch Streep laughing at her character instead? Does this distinction even matter in She-Devil?

MATTHEW: I think the distinction matters, particularly considering the mixed feminist messaging that plagues She-Devil, adapted from British novelist Fay Weldon’s popular "The Life and Loves of a She-Devil" by two male screenwriters, Mark R. Burns and Barry Strugatz, who had previously teamed up a year earlier to pen the script for Jonathan Demme’s utterly infectious Married to the Mob, whose magic and imagination are utterly nonexistent on this project. The odd assemblage of actors and colorful shot compositions of She-Devil, which marked Streep’s first film with a woman director, give you an idea of the Demme-esque comedies Seidelman might have made with better material. Unfortunately, Burns and Strugatz can’t seem to make up their minds about just how far to take Weldon’s spiky revenge saga or whether Barr’s Ruth is a figure for us to champion or chaff. It doesn’t help, either, that Barr, who was always best when serving as her own self-satirist and narrator, plays the role all too safe, turning Ruth into little more than a receptacle for the writers’ mean-spirited one-liners about her looks and demeanors.

And then, of course, there’s Streep, who must have realized midway through this shoot that transcending this already creaky premise was not remotely feasible. Accordingly, Streep plays this specious character the only way she can without embarrassing herself or standing at a remove from her fellow actors and collaborators, however subpar their efforts. (There is arguably nothing more hilarious in She-Devil than the idea of a ladykilling lothario being played by the fairly hunky but perpetually white-bread Begley, Jr., who is always best when embodying oblivious dunderheads for Christopher Guest or on Arrested Development.) She-Devil desperately needed more focused writers and a firmer directorial hand, but I think Streep actually acquits herself well enough in She-Devil to (mostly) stave off the insipidness that surrounds her. No, there’s not a single shot that belongs anywhere near a career highlight reel. And yes, there are more than a few moments in which Streep suffers as a result of their sheer unplayability; you can practically feel their air seep out of the soundstage during a cringe-inducing, late-film scene in which Streep’s Mary wildly takes back her home from her reckless stepkids, backbiting mom, and begrudging butler.

Streep’s clueless, unflappable imperiousness definitely emerges as the film’s most inspired comedic element, but to what end? Everyone, from the screenwriters to the wardrobe department that has decked Streep out in an endless succession of frills, scarves, and wide-brimmed hats, has decided to render Mary absurd, and the actress doubles down on this. She plays Mary Fisher like a sedated Glinda the Good Witch, but with a hollow, rotten core. Streep keeps her line readings breezy and her body language self-consciously doll-like if increasingly gawky, perhaps attempting to reveal a more studied quality to the conception of “Mary Fisher” that goes absolutely unnoticed by her fellow filmmakers. It must have been an exciting prospect at the time to see Streep experimenting with broad comedy, but her talents prove far too character-specific to coalesce with this ineffectual, gag-minded farce. Streep’s presence here is peculiar and underchallenged, only ever acutely felt in a requisite scene in which Mary, now a spurned spouse herself, studies herself in the mirror, poring over her appearance and fiddling with her features. It’s the type of poignant, truth-telling scene that feels airlifted in from a totally different movie, one that might better appreciate its actors as something more than fodder for dim punchlines and forgettable bits of slapstick.

Like the film that surrounds it, the pleasures in Streep’s performance are few and fleeting. Luckily, there were would be markedly more ingenious Streep comedies within the next several years. But for now, I’m still trying to wrap my head around what compelled Streep to lend her services to a project with such dubious gender politics, ending her decade of complex, willful women with what may very well be the most hatefully-conceived character she has ever played.

Next week: Postcards from the Edge (1990)