by Lynn Lee

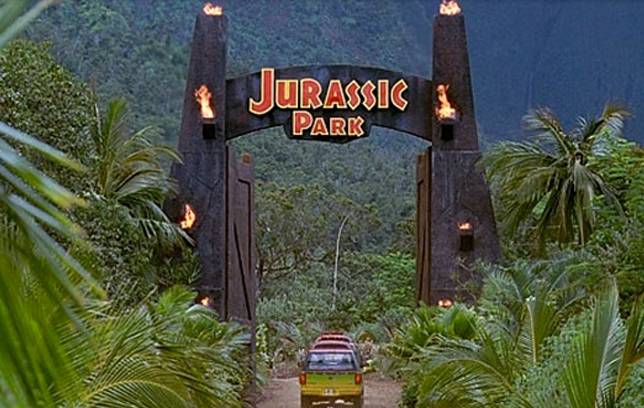

June 1993. It was my birthday, and I’d invited a group of my girl friends over for a small celebration that would include a movie outing. I don’t remember exactly why I picked Jurassic Park. I hadn’t read the book, I wasn’t yet a full-on movie buff, I didn’t like scary movies, and I wasn’t really into dinosaurs. Yet something about the tremendous buzz surrounding this “adventure 65 million years in the making” must have penetrated my social bubble because I remember us all being excited to see it.

Whatever our expectations were, Jurassic Park blew them away. From the moment that opening eerie chorus and single bamboo flute dissolved into the rustle of an unknown, unseen thing in a crate that within three minutes lay savage waste to one unfortunate worker, we were all transfixed in our seats and couldn’t have moved if our lives had depended on it...

I still remember gasping with the rest of the packed theater every time a dinosaur came crashing through a wall, coiling up internally from the unbearable tension of the raptor kitchen sequence, and cheering wildly when T-rex saved the day. We emerged from the theater feeling not like we’d seen a movie but like we’d had an EXPERIENCE. Our enthusiastic chatter afterwards must have impressed my parents, because I remember that as soon as my party disbanded, they went to see the movie themselves—and enjoyed it as much as we did.

Since then, I’ve seen Jurassic Park so many times I’ve lost count. I still firmly believe it’s one of Spielberg’s best. While it’s hard to articulate exactly what makes it so effective, even on re-watch, I’ll just pinpoint some of the key ingredients to its special sauce...

The suspense of the unseen

The genius of the way this movie was marketed, with only the briefest and most tantalizing peeks of the dinosaurs, was reflected in the structure of the movie itself, which takes its sweet time to show us its main attractions. Jurassic Park takes a page out of Spielberg’s Jaws playbook, especially in that opening scene where we don’t have to see the creature to sense its viciousness and share the terror of its first victim, whose demise also happens out of our sight. When the raptors do finally appear in full view, they live up to every bit of terrified anticipation they’ve built up, and then some. Our first signs of T-rex are similarly understated and delayed: as the storm draws near and our stranded protagonists wait in their disabled cars for the power to come back on, the prevailing mood’s mainly one of boredom and irritation – until young Timmy spots the faintest tremor in a cup of water.

The genius of the way this movie was marketed, with only the briefest and most tantalizing peeks of the dinosaurs, was reflected in the structure of the movie itself, which takes its sweet time to show us its main attractions. Jurassic Park takes a page out of Spielberg’s Jaws playbook, especially in that opening scene where we don’t have to see the creature to sense its viciousness and share the terror of its first victim, whose demise also happens out of our sight. When the raptors do finally appear in full view, they live up to every bit of terrified anticipation they’ve built up, and then some. Our first signs of T-rex are similarly understated and delayed: as the storm draws near and our stranded protagonists wait in their disabled cars for the power to come back on, the prevailing mood’s mainly one of boredom and irritation – until young Timmy spots the faintest tremor in a cup of water.

This approach, perhaps inevitably, got left by the wayside in the sequels, which started throwing dinosaurs at us increasingly early and often. But the OG JP’s restraint continues to pay dividends even on the umpteenth watch when you know exactly what’s coming when. You hold your breath just the same.

The visual effects

Even a quarter century later, the dinosaurs within Jurassic Park (a combination of animatronic, practical effects and computer animation) still impress with their tangibility and lifelike movement. The sequels may have made significant technical advances, but the first one never feels any less convincing by comparison. Jurassic World, and by the looks of it its sequel, Fallen Kingdom, tried to raise the bar by creating bigger and more outlandishly monstrous, genetically altered dinosaurs while forgetting that less can be more. It didn’t take more than a pair of human-sized raptors to scare the living bejeezus out of us the first time, after all. Also, part of what made the original so appealing was its ability to evoke not only fear but our protagonists’ sense of wonder at seeing the classic dinosaurs they’d studied or seen in museums – including the gentle “veggie-sauruses” – come to life.

The stalking sequences

They set the standard for all creature features to follow. Remember those scary scenes in A Quiet Place where the monsters stalk Emily Blunt around the house, or try to get at the kids in the car? Go re-watch the raptors hunting the kids in the kitchen and the first T-rex attack in Jurassic Park, and you’ll appreciate just how heavily John Krasinski borrowed from Spielberg’s classic nailbiter.

The music

One of John Williams’ best scores, and he, like Spielberg, has a deep bench. If you love the movie, you can probably hum the two main motifs from memory like I can. One is a simple, lullaby-like melody that evokes the wistful side of John Hammond’s doomed vision, the other a soaring brass-driven fanfare that cues the Spielbergian sense of adventure we know and love. Yet the majority of the score is perfectly attuned to the tension and terror of never quite knowing when a dinosaur’s going to spring.

The cast

On its release, I remember a review snarking about how the actors’ bug-eyed, open-mouthed reactions to their first sight of the dinosaurs wasn’t going to win any Oscars. I happen to think the actors did an excellent job reacting to things they couldn’t see (the kids – played by Ariana Richards and Joe Mazzello – were particularly impressive in this regard) and that the movie was brilliantly cast – from Sam Neill’s wry, sardonic, yet comfortingly steady presence as Alan Grant and Laura Dern’s warm, down-to-earth Ellie Sattler to Jeff Goldblum’s delightfully goofy turn as mathematician Ian Malcolm (“Why am I right all the time?”), and last but by no means least, Richard Attenborough’s jovial, avuncular take on John Hammond. His performance was a major revision of the much more sinister character from the novel. The new take on the character provided a surprisingly poignant anchor to a movie that, like every good sci fi story, is fundamentally about the hubris of man playing god. His third-act reminiscence to Ellie about his first “attraction,” a flea circus, while perhaps a tad on the nose as a metaphor for Jurassic Park (and Jurassic Park), is unexpectedly affecting.

There’s so much more I could say about what makes the movie work, but I hope that’s enough to encourage you to go watch it again. It holds up marvelously, and I suspect will endure long after its multiple sequels and imitators have faded from memory.