A few volunteers from Team Experience are revisiting Federico Fellini classics for his centennial. Here's Eurocheese...

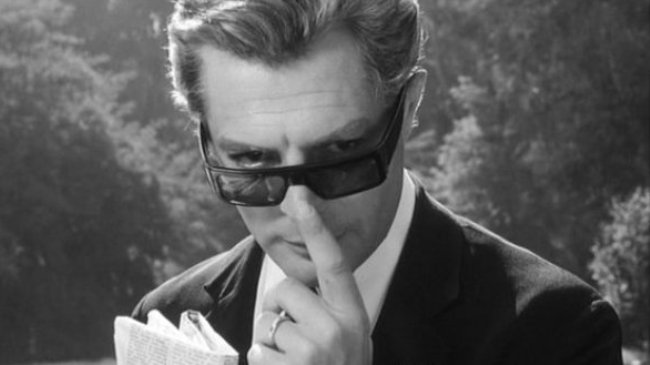

A filmmaker stands out as a master because of the distinctiveness of their voice, and how they speak specifically to the human condition. Well, that, and a filmography where we can point to classics, even stone-cold masterpieces. If I was to ask you which director seemed to examine life through a fun house mirror, you might be able to guess we were talking about Fellini. I hadn’t rewatched 8½ (1963) in several years and one of the things I had forgotten, maybe because of the joyous memories of so many individual scenes, is the way the razor sharp editing creates such a sense of panic right from the start; we're watching our protagonist suffocating with hundreds of eyes on him. The iconic image of the director flying high in the sky like a kite, only to be pulled down to the ocean, adds terror to the upcoming, more realistic scenes. This movie itself must provide answers for him to escape his terrible fate.

The way the film consistently rushes one character after another at the camera gives us a taste of the control Mastroianni’s Guido is experiencing. He's both suffering from a god complex where he can toy with the depictions he is sending us, and building towards a fate he's desperate to avoid...

Can any of these seemingly simple conversations save him? His characters even play with him, referring to the loneliness of the filmmaker, almost mocking him as he tries to track down an honest answer. He runs to the past; he runs to religion; he runs to the women in his life, from his wife to his mistress, to actresses and friends. Someone must be able to save him from himself.

What can we mak of the strange calm that creeps over the initially panic-filled proceedings? At every turn, the cinematography, costumes and set design are stunningly gorgeous. Guido may feel that he is trapped, but it's within a life of luxury, and the background of the film betrays this. Despite his crisis, he is incredibly blessed. First world problems, we might say today. Yet, luxury and privilege aside, who hasn’t asked themselves these questions of themselves: Does my life matter? Have I done everything wrong? What have I accomplished? And very smartly, at one point Guido even asks himself, “What does it mean to be honest?” How can a film, which he hopes will document his saving grace, provide any kind of truth?

Later on in the film, he has a monologue so beautiful that it deserved to be quoted directly.

“I wanted to make an honest film. No lies whatsoever. I thought I had something so simple to say. Something useful to everybody. A film that could help bury forever all those dead things we carry within ourselves. Instead, I’m the one without the courage to bury anything at all.”

And he follows in a bit, realizing...

I really have nothing to say, but I want to say it all the same.”

This has to be one of the most candid and vulnerable statements ever voiced in a screenplay. Storytelling by nature tampers with its subject, but by showing us Guido's desperation to connect, it also shows us his heart. Fellini's alter ego may be a womanizing, confused man who drags others down with his problems, but he is a human being, capable of loving and learning and sharing what he has learned with his audience. Ultimately, he must find a way to be merciful to himself rather than hating what he has done with his life, if he is hopeful to make any kind of change.

The screenplay teases this in several scenes. Another brilliant step is the running gag that Guido doesn’t have the ability to pay attention to literally anything. Sitting with a group of Catholic leaders, they meditate on the lovely sounds of a bird in the distance, while Guido is distracted by a woman passing by. Sitting with his lover, he is unable to concentrate on their conversation, constantly looking away. What else might he be missing? What else can life be trying to tell him? He literally can’t see the world in front of him, so it’s no surprise that he’s in a constant panic.

I’d be remiss not to mention the famous scene where, after Guido’s wife (played by Anouk Aimée with a refreshing charm and insight) seethes at seeing his mistress prance in front of them at breakfast, and a smirking Guido alters the situation to play as he likes. First he makes the two women into friends, then hilariously goes a step further and throws all women he finds attractive into an insane funhouse dream where they worship him as a god. He arrives with presents to their tittering delight, but the scene quickly changes when the women realize one of them is being cast “upstairs” because he has deemed her insignificant. The women realize their fate and demand their freedom, twisting his laughable dream into a nightmare, with Guido fighting them off with a whip. His wife, even as a fictional character who has bowed to all his wishes, knowingly tells the other women that every night ends the same way. His dream, even if its viewed in jest, is ridiculous and unattainable.

Even so, as we ramp up towards the finale, where Guido is cornered into answering all of life’s questions, he ultimately finds his way out. After a brief allusion to shooting himself, which appears to indicate that his perfect film is over, he reappears to direct a scene where he can dance with all of those who are important to him. The director asks their forgiveness and owns his confusion as an ongoing struggle. In the meantime, he will dance! Perhaps this is the best any of us can hope to accomplish – dance with our demons rather than fearing our fate. His final word to his wife ring poignantly, and remind us why Fellini’s films are so moving.

Even so, as we ramp up towards the finale, where Guido is cornered into answering all of life’s questions, he ultimately finds his way out. After a brief allusion to shooting himself, which appears to indicate that his perfect film is over, he reappears to direct a scene where he can dance with all of those who are important to him. The director asks their forgiveness and owns his confusion as an ongoing struggle. In the meantime, he will dance! Perhaps this is the best any of us can hope to accomplish – dance with our demons rather than fearing our fate. His final word to his wife ring poignantly, and remind us why Fellini’s films are so moving.

Life is a celebration. Let’s live it together!”