"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

Last week’s column on Suddenly, Last Summer was a bonus sidebar to our ongoing Montgomery Clift retrospective. Today, I offer a diversion from our wall-to-wall Monty programming, in the form of a tribute to someone else’s centennial: Melina Mercouri. None of this film star's movies were nominated for Best Production Design at the Oscars, but I adore her anyway. And one of her films, made at the peak of her fame, is a perfect fit: Topkapi (1964)

Last week’s column on Suddenly, Last Summer was a bonus sidebar to our ongoing Montgomery Clift retrospective. Today, I offer a diversion from our wall-to-wall Monty programming, in the form of a tribute to someone else’s centennial: Melina Mercouri. None of this film star's movies were nominated for Best Production Design at the Oscars, but I adore her anyway. And one of her films, made at the peak of her fame, is a perfect fit: Topkapi (1964)

Mercouri’s brand, so to speak, was one of obstinate vitality. In Stella, her film debut, she played a nightclub singer who simply refuses to be married, even at the expense of love. Her character in Never on Sunday, for which she received her only Oscar nomination, insists upon her own chipper versions of the Greek classics. Medea, who didn’t really murder her children, gets her husband back and they all go to the seashore. Mercouri’s signature vivacity is always at odds with her surroundings, defying the rules of both tragedy and society.

But the visual climax of this attitude comes in Topkapi, for which the entire world seems to have been refashioned to fit the expectations of Mercouri’s persona. She even introduces it, casting the world as a funfair even before the opening credits...

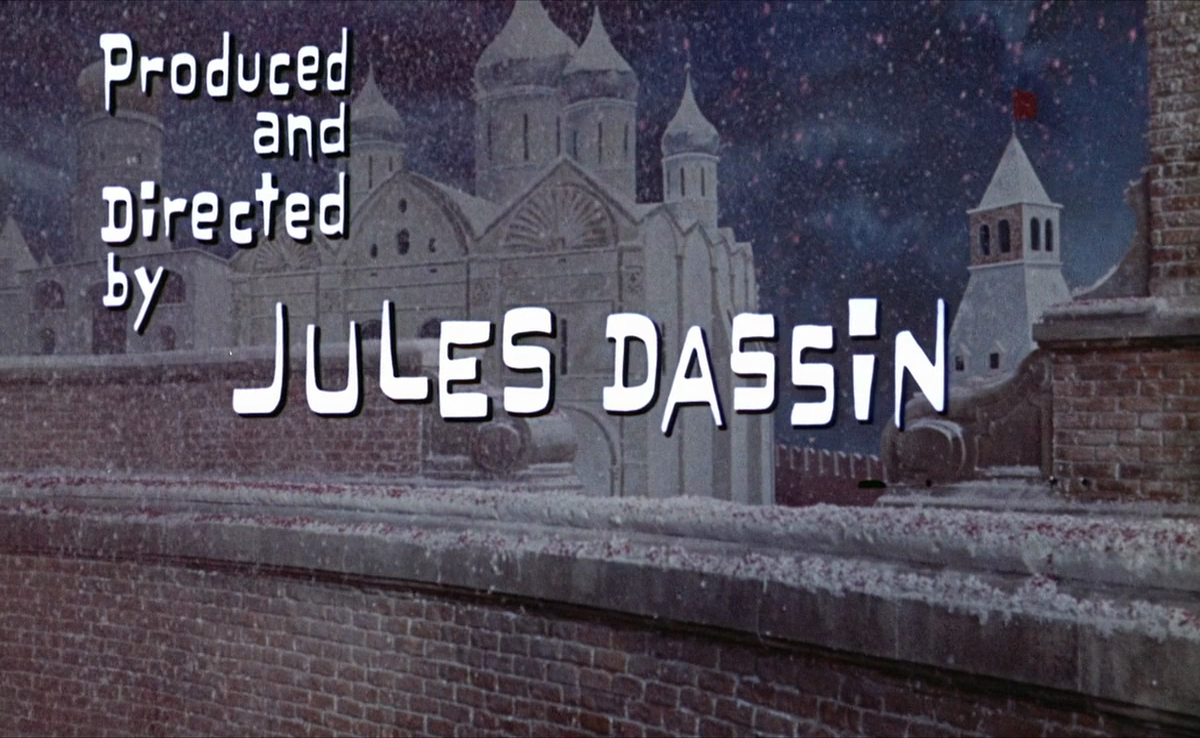

Topkapi is a heist film, one of many collaborations between Mercouri and her husband, director Jules Dassin. She plays Elizabeth Lipp, a world-class jewel thief. A pseudonym, of course, but she’d prefer if we used it. She welcomes us into a carnivalesque dreamscape, a kaleidoscope of electric games and wax figures, Stalin and Salome among them.

It’s a casino in which Elizabeth is both gambler and dealer. Or perhaps she’s a 10th muse, responsible for the art of theft. Her laughter alone, ricocheting off the roulette table, could inspire all sorts of brilliant capers.

Eventually Dassin pulls back enough to show that this is a real place, the funfair near the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. Elizabeth then leads us into the Treasury.

The spoils of an entire empire rests inside, golden chalices and bejeweled thrones. She seems right at home, here in the unguarded vault of her mind’s eye.

The silver teapots and gold candelabras are just window dressing, however. The real prize, the one she would move heaven and earth to steal, is a dagger. Fastened to the mannequin of a faceless sultan, it glimmers from behind a glass case. But will it ever be hers?

After the opening credits, the dreamscape settles into a semblance of reality. But the work of art director Max Douy and set decorator André Labussière is to echo Mercouri’s magic. They create a free-wheeling atmosphere in which the threat of getting caught remains technically possible, but far too inconsistent with the vibe to actually worry about.

Elizabeth’s first recruit is an old flame, Walter Harper (Maximilian Schell), who she meets in the fog.

He leads her to Cedric Page (Robert Morley), an eccentric British toy maker.

Page’s workshop features a hidden door in a bookcase, an automated cocktail cart, and a motorized talking parrot. Elizabeth may have temporarily left the circus, but its spirit follows her everywhere.

The only person not having fun is Arthur Simon Simpson (Peter Ustinov), the small-time con man who Elizabeth and Walter pick up in Greece. They trick him into driving their car to Istanbul, laden with hidden weapons. But even the Turkish border, an ostensibly threatening locale, looks a bit like a circus prop.

Arthur winds up in a Turkish jail, which stands out as one of the few severe sets in the film.

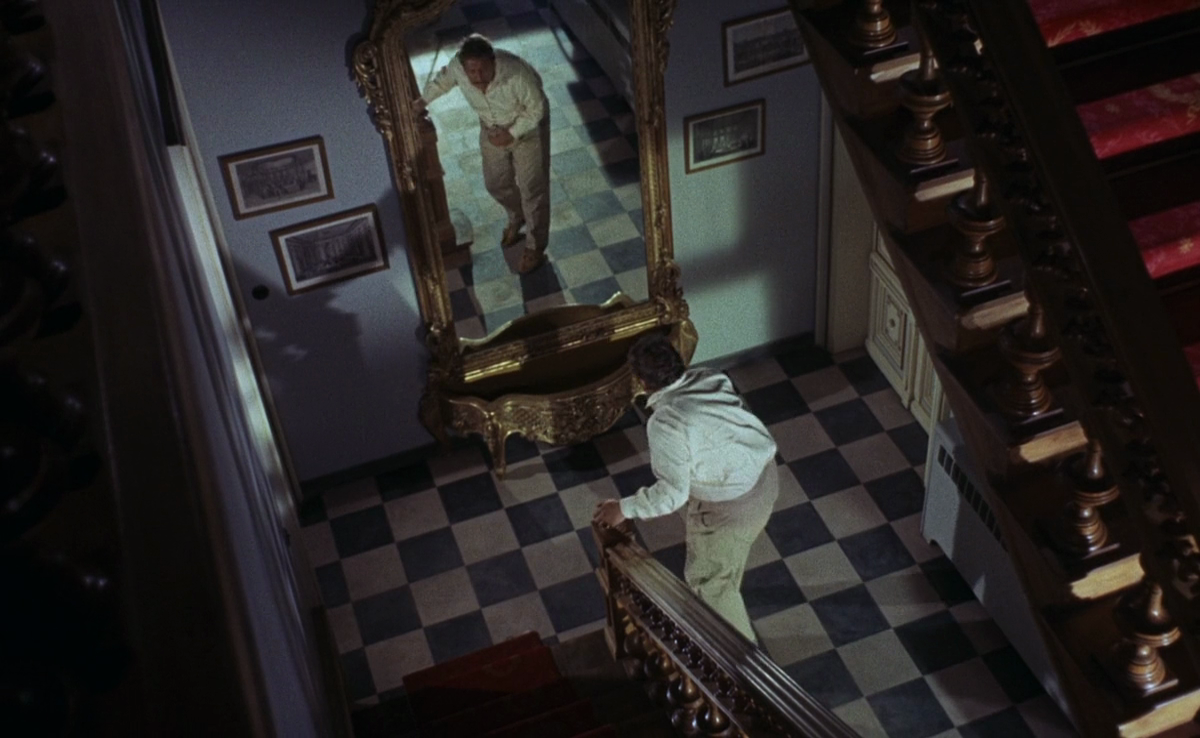

Still, it’s a temporary shock. He’s released as a newly-minted undercover agent of the Turkish police, a largely incompetent informant within Elizabeth’s team. Their safe house is a hall of mirrors to poor Arthur.

But he really has nothing to worry about. The heist is facilitated by this same spirit of production design. Topkapi Palace turns out to be perfectly designed for a robbery, down to the last detail.

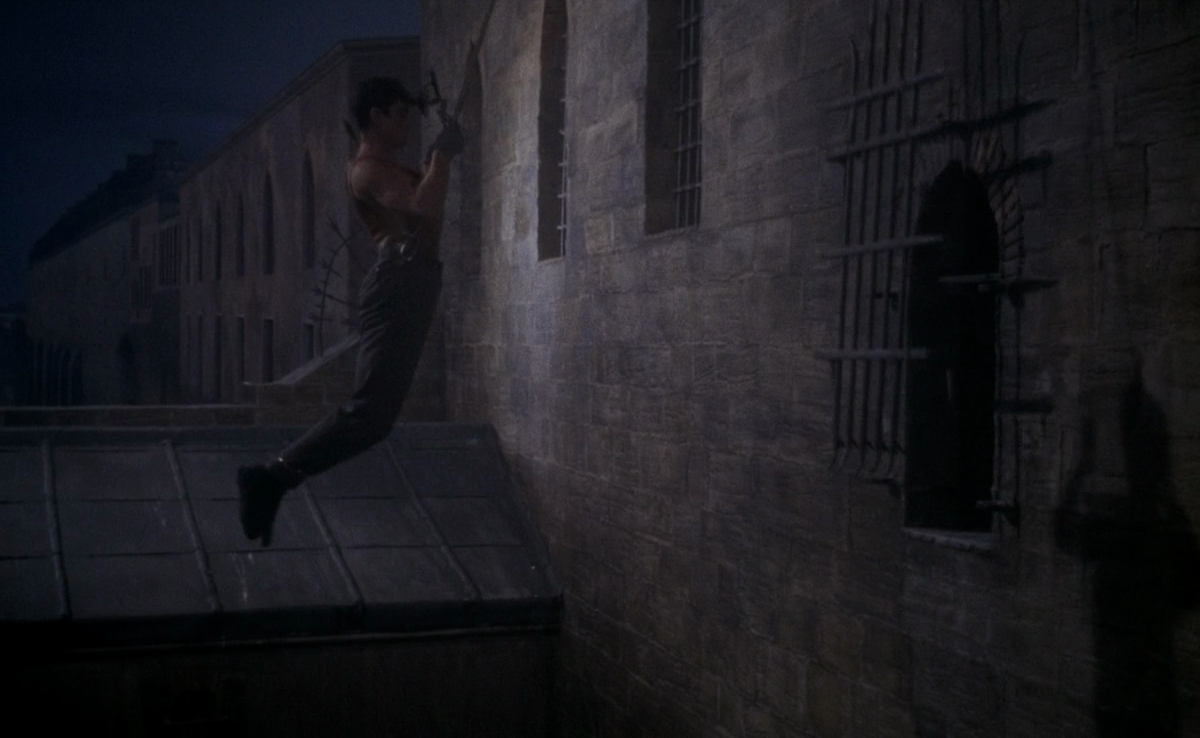

Its windows are just right for an acrobat (Giulio, played by mime Gilles Segal) to leap through, once the conveniently hung grate is lifted up.

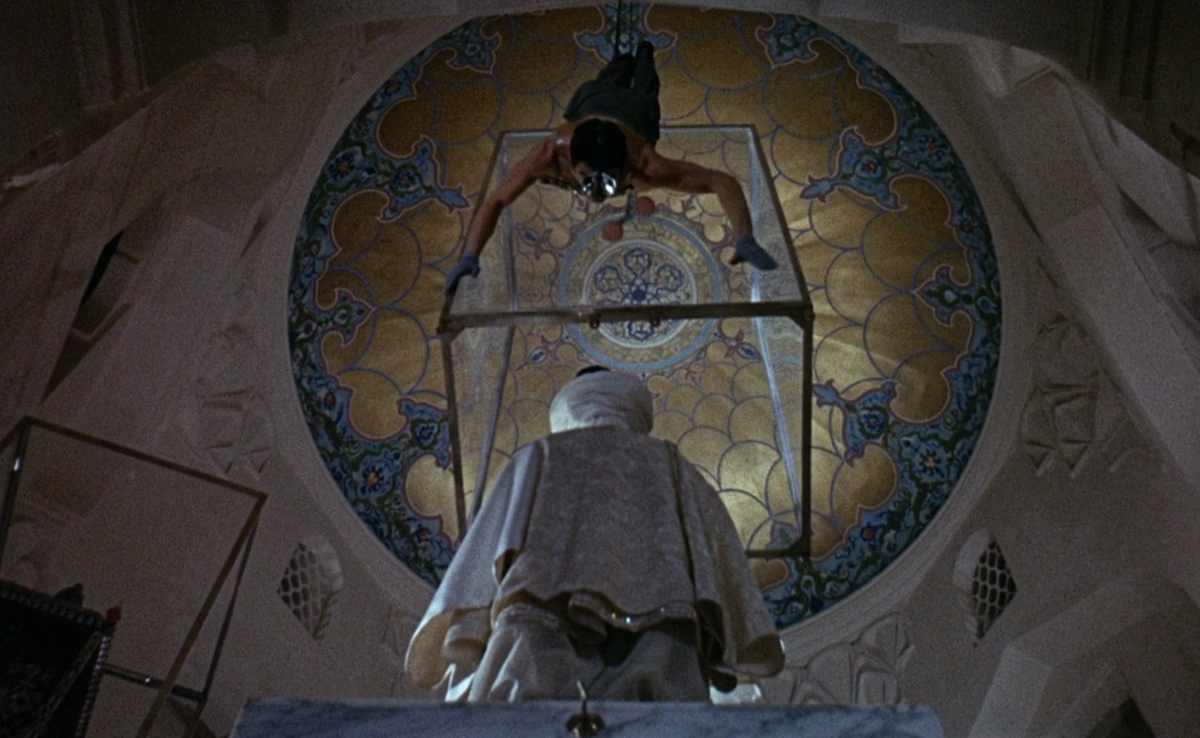

From there it’s a quick scurry to the next window, a beautiful stained-glass number with its own landing platform.

This isn’t a criticism. Dassin, Douy and Labussière understood that a heist sequence needs a sense of style. Tension and the threat of discovery are important, sure, but so is visual pleasure. A great heist should be like watching a Rube Goldberg machine or a magic trick.

From the first hasty steps to the final zipline off the roof, the heist in Topkapi is very satisfying.

Of course, spoiler alert, it’s all for naught. Everyone winds up in prison, the walls of which look more like a Saul Bass cartoon than harsh stone.

But has Elizabeth given up? Absolutely not. She’s already moved on to her next target. Where? A secret stairway in the Kremlin, leading to the Romanov crown jewels. She and her compatriots spend the closing credits trudging through a Russian landscape, even more like a cheap carnival backdrop than the Istanbul funfair. Once more, everything is right with the world.