It's October, a season for spookiness and horror movies, for nightmares and ghouls. It seems only appropriate that the Almost There series takes a look at a performance in the horror genre, though it's hard to find examples that fit the criteria. AMPAS is famously allergic to most horror and few actors have been recognized or come close for that genre.

Inspired by the month and the Criterion Channel's new Joan Crawford collection, I decided to take a look at one of the actress' most contentious and controversial achievements. One speaks of that terrifying occasion when Joan and Bette met onscreen, the clashing of two titans and two acting styles, the epitome of Grande Dame Guignol. That's right, it's time to explore What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?...

The behind-the-camera shenanigans involved in the making, promotion, and awards race of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? have been told and retold many times before. Most recently, Ryan Murphy gave us Feud, where rumor is taken as truth and scandalous drama reaches the level of myth. To retread on beaten paths seems futile, especially when our topic of interest isn't gossip, but performance.

Joan Crawford may have cost Bette Davis a third Oscar win and the intersection of their professional and personal relationship may have been nothing short of catastrophic. However, to let such sensational business overshadow Crawford's performance feels unfair. At a first glance, Crawford's success in the movie almost seems like a success of casting more than an acting triumph, but first impressions are often wrong.

As Blanche and Jane Hudson, Crawford and Davis are a match made in hell of sisterly spite. In their youth, Jane dazzled audiences as a kid star of vaudeville but, as the years went on, it was Blanche who rose to the top, turning into a Hollywood sensation. Embittered, half-crazed by jealousy, drunk and hateful, Jane rammed her car into Blanche one night, paralyzing the other woman from the waist down and condemning her to a wheelchair. At least, that's what the stories say.

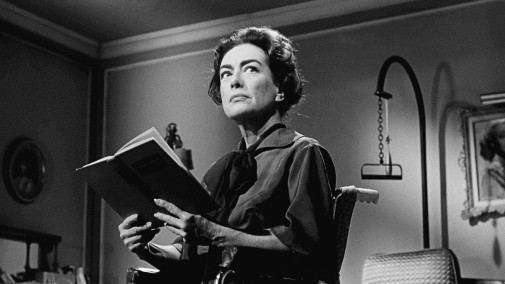

When we finally meet the old sisters after a long prologue, they're the sole inhabitants of a dilapidated mansion in suburban Los Angeles. Blanche has aged into a serene star of yore, all faded glamour, and magnanimous meekness. She's confined to a wheelchair and rarely leaves her upstairs bedroom, depending on Jane and their maid, Elvira, to take care of her. As for the other Hudson sister, she's taken on the role of reluctant caregiver with as much resentment as expected.

Throughout the picture, we see them spiral into absolute destruction, as Jane loses her sanity and Blanche is made into a prisoner of her mad sister, starved, bound, and beaten without mercy. The behavior of the sisters and their odd dynamic is further highlighted by the metatextual charge its actresses bring to the scene. Their animosity was well-publicized, and their differences as performers were no less obvious.

To put it in blunt, a bit too simple, terms, Crawford was a movie star who made the labor of acting seem impossibly beautiful, vaguely arch, and effortless. Davis, in contrast, was a showier sort of screen presence, a character actress in leading roles more than a classic star. One can never miss her capital-A Acting, each interpretative choice showcased to great effect and often verging on fearless grotesquerie.

Davis' Baby Jane Hudson is a miracle of horror movie acting, justly nominated for the Best Actress Oscar, but we shouldn't underestimate Crawford's efforts. The picture wouldn't work without the huge contrast between two actresses and their approach to the horror genre. Davis' bombast needs a counterbalance and if Crawford had gone full-on hag like her costar, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? wouldn't have worked half as well as it does.

Crawford's first line – "Still a pretty good picture." – said while Blanche admires one of her old movies on TV, immediately complicates our initial conceptions of the character. She shines with pride and is happier at that moment than in the rest of the entire movie. Crawford undermines the possible readings of her character as a martyr. There's always something more under the surface of Blanche's beatific suffering. Maybe it's the sharp resilience, a hint of diva pride, or the abrasive, underplayed, contempt she has for her sister.

Comparing the actress to her young self on television is also a stark exercise, not just because of her aging but also because of her screen persona. Crawford’s glamour has faded, the glittery façade now full of cracks, reflecting the changes in the industry. The mannered gesture creaks with each change of pose and Blanche is brittle. That said, she's also strong, a monument of lost stardom that's much more resilient than she looks. Blanche may be in a wheelchair, but her mind is sturdy unlike that of her sister. Furthermore, Crawford refuses to portray Blanche as frail in these early moments.

Her posture is straight, shoulders held back even though she's forced to live sitting down. There's an imperiousness to her bearing too, and her maneuvering of the wheelchair is always done with confident athleticism. The actress doesn't spothlight the handicaps of her character, leaving such haggard physicality for the later stages of the drama, when Blanche's really in distress and not merely living her day-to-day existence as any person who's grown used to their disability.

Her arc is that of a woman in control who's quickly losing that very same dominion over her life. Despite her frail state, Blanche's needs rule the existence of her and her sister. There's even a sense of chilly authority about her, a bit of benevolent noblesse oblige to the way she carries herself and talks about Jane. Because of that, when it all comes crashing down, it feels all the more sordid and tragic. A star like Blanche was, like Crawford was, isn't meant to have their light smeared in dirt, blood, and hate.

Blanche is keenly aware of what Jane's capable of, but she thinks she can handle it. You notice it in the way she listens to her sister's cries echoing through the empty house, how she softens her voice when talking to the other woman as if she were a rabid animal who might attack at any sign of danger. Thinking she could eternally control Jane was Blanche's biggest mistake, her folly, the signing of her death warrant. Blanche never really knew to what extremes her sister would go even if she knew there was twisted ill intent fermenting in Jane's soul.

It's painful to watch someone as lucid as Blanche lose everything in the manner she does, her autonomy slipping through the fingers like licks of smoke. Crawford plays Blanche's degradation as tortuous, visceral instead of beatific. Just look at the actress' portrayal of Blanche's brutal hunger. See how she devours old bonbons, how her face contorts in ravenous relief. One can almost feel the hunger pangs and the twisting of her empty stomach around the sugary treat. She says it all with no dialogue.

Crawford had a lot of Silent film experience, and her expressive face showed the plasticity of silent acting well into her twilight years. She dominates a scene with little more than the nervousness of twitchy looks and a quivering lip. It's humanity painted with shades of artifice, a lie that speaks the truth. That's not to say her line delivery is bad. The airiness of her voice is of particular value, varnishing any interaction between the sisters with insincerity and discomfort.

Before I'm through singing the praises of Crawford's Blanche, one must pay respect to some moments of stand-out brilliance. Her hesitation over a food tray is pure theatre of human agony. Later, during the second incident with a monstrous meal, Crawford brings the performance to a boiling point of despair. The score does everything in its power to delineate the emotion of the moment, but it's Crawford's hysteria that sells it.

One also finds much to admire in the raw physicality of the stairs scene, when Blanche goes down the steps with much effort. Again, she's acting with her body and face, illustrating the woman's plight without the benefit of all the dialogue and grotesque mugging that Davis indulges in to great effect. Suitably, by the end, Crawford leaves us with a haunting pose, carrying meaning with no words. Her last closeup is the stuff of horror movie iconography, jagged and bug-eyed, a last tableau for Blanche's punishment.

As stated before, there's little need to dwell on the Oscar race since it's as famous as this movie's stars. The nominees that year were Bette Davis for this same picture, Anne Bancroft for The Miracle Worker, Katharine Hepburn for Long Day's Journey Into Night, Geraldine Page for Sweet Bird of Youth, and Lee Remick for Days of Wine and Roses. AMPAs chose Bancroft, and Crawford accepted her Oscar live on TV. I'd have voted for Hepburn, but this is one of the all-time great lineups. That being said, Crawford's presence could have made it even better and less contentious.

Regardless of her offscreen actions and all the related drama, do you think Joan Crawford deserved a Best Actress nomination in 1962?