By Glenn Dunks

It has been a while since I was quite so turned off by a documentary as quickly as I was by Kingdom of Silence. Well-intentioned in its exploration of the special relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia, and how journalist Jamal Khashoggi came to be executed, but built in a fashion that mimics some sort of Tony Scott crime thriller from the 1990s. Using every trick in the book when the story at its core is so interesting only seeks to diminish its impact.

It has been a while since I was quite so turned off by a documentary as quickly as I was by Kingdom of Silence. Well-intentioned in its exploration of the special relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia, and how journalist Jamal Khashoggi came to be executed, but built in a fashion that mimics some sort of Tony Scott crime thriller from the 1990s. Using every trick in the book when the story at its core is so interesting only seeks to diminish its impact.

Director Rick Rowley, an Oscar-nominee for 2013's Dirty Wars, isn’t just content with verite filmmaking to create a sense of urgency. Rather his film is edited through a woodchipper, it has an over-abundance of unnecessary focus pulling and slow-motion, plus over-the-top zooms and anonymous overhead camerawork of cities and crowds implying menace everywhere you look. All played against an incessant droning soundtrack full of technological bleeps right out of The Matrix. And that’s just its first two minutes and 51 seconds.

The cumulative effect of it all is exhaustion.

I suspect from a storytelling point of view that the film suffers from telling two stories at once, both of which overlap and yet have stark contrasts that affect the way an audience might engage with them. The film is at its best when it is matter-of-factly detailing America’s special relationship with Saudi Arabia and how American presidents have been forced to ignore many undemocratic realities for the sake of oil and money. To be in bed with Saudi Arabia is just the done thing for presidents far beyond Donald Trump. The passage of the film built around the 9/11 terrorist attacks is particularly unkind to these realities. Rowley is clear-eyed and focused in these sections, his storytelling aided by plentiful archive footage and diplomatic experts, tying it in well with Jamal’s story as something of a chosen son among the ruling class of Saudi Arabia.

The movie is murkier, however, on the subject of Khashoggi himself. By the film’s own admission, he is a secretive individual with the film’s own talking heads informing us that we can never truly know his whole story. Even his friends didn’t know all the facts of his life, which makes the passages devoted to him somewhat of a bigger narrative mystery and which is probably partly why then that the film is played as some sort of Hollywood production.

The film attempts to chart his journalistic career, most importantly his early access to Osama Bin Laden in the 1980s following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He is shown to be a loyal Saudi man who was granted incredible access by previous leaders. While the film remains cagey in exploring the beginnings of the man’s strong Saudi nationalism and the continued motivations behind it, there seems to be no denial that he reached a breaking point with the installation of King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud. There are hints of guilt in Khashoggi’s later actions demonstrated most powerfully by agreeing to speak to a group of families who are suing the Saudi government for having granted finance and resources to the Saudi men who ultimately carried out the 9/11 attacks.

These unknowable facets of Khashoggi’s life are quite alarmingly set against the shocking truths that we do know about his death. But, again, Rowley and in particular editor Alexis Johnson (a frequent collaborator of Alex Gibney who is an executive producer here), suffocate the narrative with absurdly exaggerated cutting. What should be the film’s key moments for solemn reflection are turned into needlessly fussy sequences that do not get the chance to breathe and let the viewer take in what is being presented. Audio and on-screen transcripts of the moments just before and after Khashoggi’s death are horrific, heart-pounding stuff on their own without the need to be portrayed as techno-thriller gobbledygook.

Another, even more egregious, is when Khashoggi’s fiancé, Hatice Cenzig, gives testimony to a United States human rights committee in Washington. Her words are given just 30 seconds of screen time and even then, it is cut nearly a dozen times (I counted, it’s eleven). We see Cenzig up close and from afar, on a television monitor, and behind a camera. We even see her in an upside-down reflection on a table for some reason. Three sentences of speech yet not a moment of stillness for a woman whose husband was executed and whose aching plea for justice was being ignored by the president. Even when it then cuts to Cenzig in an interview, crying, the camera zooms and refocuses and shifts. It’s like that ridiculous Bohemian Rhapsody scene with all those edits for a character to sit down in a chair. It’s just too much.

I found myself conflicted by a lot of the movie. I found much to be intrigued by it on a geopolitical level and many of its talking heads are clearly smart people that I enjoyed listening to. But the movie is made in such a way that it renders what should be even the quiet and plaintive moments into a frenetic dog’s breakfast of filmmaking tricks and gimmicks.

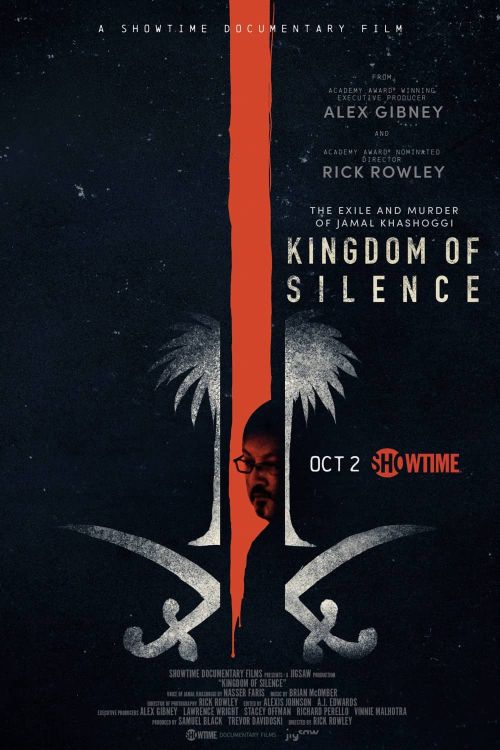

Release: Kingdom of Silence is streaming on Showtime as well as for free on YouTube for Americans. I'm not sure about other countries, but for Australian readers it is currently streaming on Stan.

Oscar chances: Probably good. Dirty Wars was a nominee, albeit in a different time for the branch. As the only major doc about Khashoggi, however, it probably has a leg up. I don't know if this is really their cup of tea these days, but I wouldn't be surprised at all to see it make the shortlist.