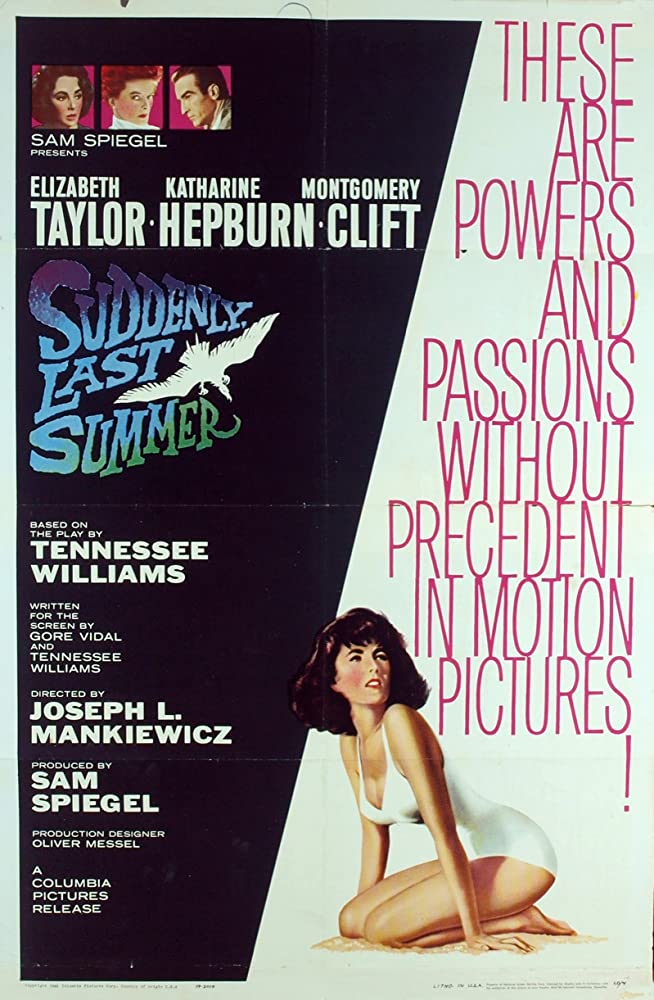

As a special side dish to our ongoing Montgomery Clift Centennial celebration, The Furniture (our series on Production Design) is looking at one of his most fascinating pictures...

Saint Sebastian had to be martyred twice. Violet Venable (Katherine Hepburn) tells his story with a certain vicious pride, lending her own Sebastian a supernatural authority. The saint was shot full of arrows but survived, miracuously, only to be beaten to death with cudgels. The first death has been depicted by countless artists, a hauntingly beautiful and frequently homoerotic image. The second, meanwhile, is unspeakably violent and ugly. It’s almost forgotten, a brutal footnote to a transcendent aesthetic.

Mrs. Venable’s Sebastian, however, gets it in reverse. As is revealed at the end of Suddenly, Last Summer, he was torn limb from limb under the white hot sun of Cabeza de Lobo. And for what crime? In accordance with the aging Hays Code, it appears to be his homosexuality. But beneath this ultra-thin surface lingers something much darker...

Sebastian’s vice is his totalitarian snobbery, his utter lack of empathy, his allegorical selfishness. To quote his cousin, Catherine (Elizabeth Taylor), Sebastian “uses people grandly, creatively, almost like a god.”

And so he lives beyond his demise, though not in body. Instead, Tennessee Williams transposes his second death onto Catherine and Violet. They each struggle to find their place in a craggy psychological landscape, cracked open in the wake of Sebastian’s hubris and hedonism. And while Joseph Mankiewicz waits until the last scene to peer directly into Catherine’s mind, the Oscar-nominated team of production designer Oliver Messel, art director William Kellner and set decorator Scott Slimon use design to suggest these shifting planes from the very beginning.

We begin in the operating theater of Lion’s View State Asylum. Dr. Hockstader (Albert Dekker) stands in the balcony, proud of this makeshift step forward for his underfunded institution. Below, Dr. Cukrowicz (Montgomery Clift) performs a revolutionary new mental health technique: the lobotomy.

Dr. Cukrowicz quiets down “hopeless cases” by removing a portion of the brain. It’s a form of playing god. Yet the physical levels of the operating theater complicate this. He may have dominion over the patient, but he performs for a more powerful man above.

And, in turn, above and beyond Dr. Hofstader is Violet. She sees this new surgery as the perfect tool to stifle Catherine, to forever protect Sebastian’s legacy. In return, she will fund Lion’s View and the work of Dr. Cukrowicz. So she invites the talented doctor to visit her home, where she makes one of the most iconic entrances in cinema history.

“Are you interested in the Byzantine, Doctor?” she asks him, crediting the mysterious, ascending throne of a Dark Age emperor as the inspiration for her elevator. “But as we are living in a democracy, I reverse the procedure. I don’t rise, I come down.” Violet passed her preference for only gazing downward on to her only son - or, perhaps, she learned it from him. Sebastian’s own innate power is a subject of constant speculation and mythmaking.

Violet then leads Dr. Cukrowicz outside, into an overgrown garden that she and Sebastian shaped into their own personal version of “The Dawn of Creation.” It seems endless, freed from the bounds of both the sound stage and physical reality itself.

This chaotic landscape stands in for the harsh creator god that shocked Violet and Sebastian in the Encantadas, where they watched countless baby turtles hatch almost directly into the claws of malevolent seabirds. This massacre changed them. In their vision of nature, the Venus Flytrap takes the place of honor.

But if this is Eden, who are Sebastian and Violet? Adam and Eve? Eve and the Snake? Or perhaps it isn’t Eden but something from another, more obscure mythology. Sebastian as a deity with no name, or at least not one that anyone can remember. And the angels of death that guard the jungle aren't talking.

Catherine, for her part, is also haunted by the persistence of Sebastian’s movable paradise. Her arrival in Lion’s View is peaceful enough, with an assurance of kind treatment from Dr. Cukrowicz. But once it becomes clear that her mother (Mercedes McCambridge) intends to approve the lobotomy in exchange for some of Violet's money, Catherine rushes off in a panic. She winds up on a catwalk over the “drum,” an enormous cylindrical room where the male inmates recreate.

The height of the bridge turns out to be no protection at all, as a number of the men find it quite easy to leap up and grab her leg. Perhaps the scene reminds her of last summer in Cabeza de Lobo, where she would use her body to “procure” young men for Sebastian. She shrieks, trapped between remembered anxieties and the present panic.

We hear over and over again that Sebastian saw himself as essentially untouchable, disinterested in the ramifications of his actions. Yet even after Sebastian’s death, Catherine cannot escape his delusion. Violet has her trapped, planning to sacrifice her niece on the altar of her son. And so Catherine, in a moment of great desperation, rushes to the women’s drum and plans to launch herself from its much higher perch.

Suddenly, Last Summer is a film of ascents and descents, fueled by its barely-repressed queer delirium and facilitated by its fervent, flamboyant production design. And yet it resists the urge to crack open the visual boundaries of the mind until the very last sequence. Dr. Cukrowicz has brought Catherine back to the garden to try, one last time, to remember what happened last summer. And so she takes us back to Cabeza de Lobo.

We see through her eyes, or we get as close to that as a screen allows. Sebastian rushes up the narrow streets of the village to escape the crowd of local boys, who have turned their vengeance into a festival of trumpet and drum. Catherine hurries after him, surrounded by the increasingly surreal suggestions of death.

At first her memories are confined to the left side of the frame, held in their proper dimension. But by the time she reaches the top of the island, things have started to fray. Even one of the skeleton angels from Violet’s garden makes an appearance.

Catherine follows the crowd all the way to the summit, where the megalithic remains of an ancient temple witness a final act of destruction. Sebastian has nowhere else to run. It turns out that he may not be a demigod after all, or at least not one that can fly. And so he is torn to pieces, an inevitable sparagmos.

Having conquered her memories, Catherine is finally free from the threat of Sebastian’s second death. As the scene settles, for a second it seems like a resolution. But suddenly it becomes clear that Catherine’s fate has simply passed to Violet. Recognizing Dr. Cukrowicz as Sebastian, she has fully reverted to her son’s world. She retreats to her elevator, which can now only ascend.