The Supporting Actress Smackdown of 1965 will be up on Sunday afternoon so here's an extra list before we get there. Before each event, I like to watch every nominated movie, even those I have already seen. Because of that, I found myself with the unenviable penance of revisiting 1965's Othello. Many of you surely did the same, exposing yourself to one of Sir Laurence Olivier's most problematic star turns, a Blackface version of Othello. I figured if I was going to force myself to watch this dirge, I should something productive with it. Hence, this write-up, in which that famous thespian's ten acting Oscar nominations are ranked...

10. THE BOYS FROM BRAZIL (1978)

As a wizened old Nazi hunter, Olivier delivers what has to be one of the worst performances ever nominated for a Best Actor Oscar. Pardon the hyperbole, but this is a disaster at every level, condensing all the actor's worst traits and impulses in a messy miasma of incompetence that's so bad it verges on hilarity. With a preposterous Germanic accent, more appropriate for a shoddy cartoon than a prestige flick, Olivier overacts the house down.

He hams it up every chance he gets, bulging his eyes to accentuate important pieces of information and delivering his lines in a sing-song cadence that always manages to leave me open-mouthed in horror. How could this celebrated actor deliver…this? And how could AMPAS see fit to honor him with a nomination? At least, they didn't throw more gold at Olivier's costar, Gregory Peck, who's as bad as the English actor but not nearly as fun.

9. OTHELLO (1965)

As someone who adores the great works of William Shakespeare, it has always confounded me why Laurence Olivier is considered, by so many, to be the paragon of Shakespearean acting. He's a very psychologically opaque actor, seldom capable of delineating silent meanings beneath the surface level of performance. That, combined with a propensity to over articulate the dialogue, makes for a very declamatory sort of thespian whose Shakespearean turns often comes off as pageantry recitation.

That can work, but it depends on the role and, more importantly, on the staging. Othello, which is closer to canned theater than most big-screen adaptations of Shakespeare, is stiff and stripped down. It's also myopically focused on the actors, most of which don't calibrate their performances to the intimacy of the movie camera. Olivier is the worst of them, delivering a shameful bit of Blackface that doesn't even have the decency of being an admirable rendition of the role. His Othello is embalmed in florid gesture and reticulated delivery, sometimes impressive as oration though never as a fleshed-out character.

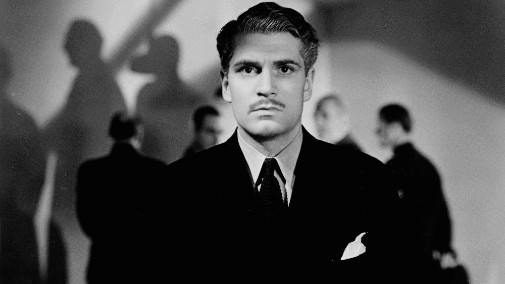

8. REBECCA (1940)

First things first – Olivier looks devastatingly gorgeous in Rebecca. It's not difficult to understand why Joan Fontaine's nameless protagonist would fall for his suave handsomeness. The reverse, however, is a bit of an unsolved mystery. Constantly shouting at his young bride and talking down to her in paternalistic tones, Maxim de Winter never shows any kind of genuine affection. Her presence irritates him and whatever love he professes to feel exists only in his hollow words.

Olivier was famously furious at Fontaine's casting since he wanted his wife, Vivien Leigh, to be his costar. That dislike suffuses the performance, overshadowing any notes of dissonant softness the actor might have added to his work. Like all beautiful people in Daphne du Maurier's novels, Maxim de Winter needs to be a confusing presence, someone whose true character is always out of reach. Unfortunately, apart from his insincere promises of love, Olivier's Byronic anti-hero is too one-note. His performance is far from bad and it works fine for the picture, but it's easy to imagine someone, even Olivier, doing a better job with the material.

7. WUTHERING HEIGHTS (1939)

Just as Shakespeare's writing is dear to my heart, so is Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights. Because of that, I have high expectations of its cinematic adaptations while also being keenly aware that the book's structure makes it incredibly difficult to transfer to the screen. Olivier's Heathcliff is suitably brooding, but he never convinces as the younger version of the character. It's especially difficult to believe his uncouth ways when everything about the actor's presence rings an aristocratic sound.

This Heathcliff never quite feels like he wants to run through the moors with Cathy, seeming more at home in Victorian parlors. That being said, Olivier's quite good in the second half of his performance, painting the character as a rotten soul overtaken by the cruel need for revenge. While the screenplay softens Heathcliff quite a bit, Olivier brings to the film some of the willful hatred that's so present in Brontë's writing. Overall, it's a sometimes flat performance that still impresses in key moments.

6. HAMLET (1948)

In Shakespeare's canon, Hamlet is the most internal of protagonists. The entirety of the role is a long meditation on self-doubt and self-destruction, revenge as a disease of the soul, and cruelty as cancer that grows out of grief. There are many other interpretations of the text proving just how complex and multifaceted Hamlet can be. Any actor willing to tackle the role deserves a modicum of respect and Olivier is no different.

Heavily influenced by Orson Welles, Expressionism, and the psychoanalytical readings of Shakespeare that were popular at the time, Olivier devised what can be described as a Freudian Hamlet. I find much to love in his directing, but one shouldn't undervalue the performance. There are issues, mostly that Olivier acts too confident and decisive for such an ambivalent character, his exteriorization of Hamlet's internal struggle a bit labored.

However, I can't help but admire the plasticity of Olivier's onscreen moodiness, how he negotiates with the stylized form, and concocts the filigreed portrait of an unrestful spirit. AMPAS surely admired him too, for they awarded Olivier with his sole Best Actor Oscar. Hamlet also won Best Picture and the thespian was nominated for Best Director.

5. SLEUTH (1972)

Sleuth is the sort of film that works better as an acting exercise than as cinema. Fittingly, both Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier tear through the material with gusto, having what looks like loathes of fun along the way. Their joy is infectious, even as their characters brutalize each other in increasingly ridiculous games of treachery and two-faced scheming. Olivier chews the scenery with purposeful shamelessness, playing a writer with too much imagination and too little sense.

It's broad and not very complex, an explosion of mannerisms and archness. Of course, demanding complexity from this text is a fool's errand and Sir Larry appears to be aware of that. For once, he's a ham and it works beautifully. At the end of this movie, I almost feel like aplauding the screen.

4. MARATHON MAN (1976)

Stillness isn't something usually associated with Sir Laurence Olivier as a performer, but his take on cinema's most fearful dentist is characterized by a chilling lack of motion. Both in walk and gesture, his Dr. Christian Szell is like a statue of crystalized cruelty, methodical in everything, from the act of dental torture to the way his face contorts in masks of congested hatred. It's superbly understated work that drains any hint of human warmth from this Nazi monster, chilling and unnerving.

Olivier's nomination for Marathon Man was his only one in the Best Supporting Actor category and, by my account, he would have made a better victor than Jason Robards.

3. HENRY V (1944)

Olivier's take on Henry V is one of the most inspired Shakespeare adaptations ever made. Instead of going against the material's inherent theatricality, he embraces it, turning the picture into a pageantry presentation that does double work as a dramatic reenactment of Elizabethan playacting and a piece of World War II propaganda. It's not in the least like the canned Othello of '65, but an exploration of film's power as a time machine and as emotional galvanizer.

All that's got more to do with Olivier's talent as a director than as an actor, but, just as his skill behind the camera is undeniable, so is the virtuosity with which he tackles the role of Henry V. What exaggeration is there, fits into the fabric of the film and Olivier knows when to hold back. He never tries to make this monarch into a human being, playing him as a national icon, a legend, a myth. He also holds back when needed, letting his imperious persona illustrate the regality of the role instead of forcing it with needless mannerisms.

2. RICHARD III (1955)

A lot of Shakespearean films suffer from a self-seriousness that is anathema to the work of the Bard. Centuries of literary canonization are probably to blame for most of the stone-faced airless renderings of his texts. Olivier's Richard III comes close to committing the same mistake, taxidermizing the history play with lush designs and perfunctory staging. However, the cast steers the film away from such misfortunes, adding a note of quasi camp to the proceedings. In other words, the actors make it fun, Olivier most of all.

Similarly to how his Henry V avoided psychological realism, so does Richard III benefit from the thespian's talent for stylization and his abandonment of naturalism. With a pronounced hunch and beaky nose, clipped stentorian speech, and snarky line delivery, Olivier's Richard is a mellifluous alien in medieval garb, so repulsive one can't help but love to hate him. Moreover, the actor savors each word, tasting the malice with his tongue in the same fashion a wine connoisseur might appreciate a prime vintage. He's wickedness made flesh.

1. THE ENTERTAINER (1960)

For this whole piece, we've explored the wondrous, sometimes perilous, artifice of Laurence Olivier's acting. He was immensely talented though not particularly skillful at evoking complex humanity, working better when there were levels of abstraction to play with. The Entertainer is the exception that proves the rule. Adapted from the stage, where Olivier originated the lead role, this Tony Richardson picture portrays a dysfunctional family of music hall performers. Olivier's Archie is a third-rate talent and part of that sad clan.

As ambitious as he is amoral, the man's a selfish cretin whose hunger for fame manifests as ravenous despair. There's a brittle mania to his showboating, a need to cover a vulnerable and horrid soul with heaps of stage makeup and insincere grins. It's a devastating portrayal of corrosive gloom, of unfulfilled need, and of performance as a façade to hide the truth of a crying clown. As much as I admire Burt Lancaster's frenetic Elmer Gantry, Olivier gets my vote for Best Actor of 1960.

How would you rank Sir Laurence Olivier's ten nominations?