With David Fincher's Mank on Netflix, many have been talking about Citizen Kane. The writing of Orson Welles' putative first feature (technically, though unfinished, Too Much Johnson precedes it by three years) is central to the new movie, but the narrative is far more interested in the 1934 California gubernatorial election than in the shooting of Kane. We never see cameras rolling on that which has been, at one point, considered the best movie ever made. Whether you agree with that hyperbolic title or not, it's undeniable that it's one of the most written about works ever produced by Hollywood, with essays such as Pauline Kael's Raising Kane enshrining the picture in prestige and controversy.

While I admire Citizen Kane and find it a masterpiece, I must admit to being far more fascinated by Welles' later efforts. Through exiles and a myriad of unfinished experiments, Orson Welles' filmography extends well beyond Kane…

Any personal musing of mine about the legacy of Orson Welles would be incomplete without me mentioning the blissful fact that I watched the majority of these flick on the big screen. That was possible thanks to the Portuguese Cinematheque, which presented a retrospective on Welles to celebrate his centennial in 2015. I spent many an afternoon letting myself be spellbound by what I saw projected on the silver screen, immersed in their mysterious allure.

The majority of those films were unknown to me, chronically under-discussed, and presented in different versions. It was like discovering some lost world of cinematic expression, a weird branch of Hollywood filmmaking that lost its mind and went wild in the old continent, a Shakespearean antithesis to Olivier's Bard adaptations that sacrificed rigid theatricality for lunatic cinematography. In many ways, watching Citizen Kane felt like homework. Discovering Welles' later pictures felt more intimate, personal, and idiosyncratic, just like the movies themselves.

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS (1942)

Ravishingly shot by Gregg Toland, this Gilded Age family drama chronicles the titular clan's degradation over the years. From what we can see on the picture's present form, it's a work of directing even more sophisticated than Kane, more ambitious too, almost radical. While singing a funeral march for a dying breed of American aristocracy, Welles paints the portrait of a changing world with brushes dipped in venom, pencils filled by a lead of fossilized humanism. A haunting in celluloid, it's a film about ghosts wailing as they slam against modernity and find themselves obsolete.

The Magnificent Ambersons is streaming on TCM.

THE STRANGER (1946)

Welles' feeble attempt at proving he could do commercial Hollywood Pablum was a shot in the foot. By far the least interesting of the director's finished pictures, it does feature some nifty camerawork, a spiffy symbolic clock tower, and the cineaste's unhinged performance as a Nazi murderer hiding in an American small town. Conventionalism was never Welles' friend, not even when clothed in the trappings of neurotic postwar film noir. Effective but ultimately disappointing.

The Stranger is streaming on Amazon Prime Video, Starz, Kanopy, and other services.

THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI (1947)

Its dizzying conclusion is justly iconic, but there's much more to The Lady from Shanghai than its labyrinthic mirrors. Above all else, the movie represents an attack on the institution of stardom itself, on Hollywood, twisting the persona of Welles' wife, Rita Hayworth, in bizarre, cruel configurations. Through a gangrenous descent into film noir hell, one feels themselves lose one's mind while witnessing the visual marvels the filmmakers have conjured, the sonorous distortions and dialogue philtered through clouds of intoxicated mania.

The Lady from Shanghai is streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

MACBETH (1948)

The director's first big-screen Shakespearean adaptation was his last American production before he exiled himself in Europe. Produced with a low budget and rudimentary means, the Scottish play gains a primordial sense of wrongness when thus presented. It's s a shadow play unraveling between rocky ravines, featuring kings costumed in cardboard crowns and armies turned into forests of spears. The viewer feels that there's strange alchemy at play. One that combines a quasi-minimalist design with Expressionistic form and a cast of actors willing to go to extremes to find (or not) the ugly truths of their roles.

OTHELLO (1951)

A kaleidoscopic shattering of Shakespeare's Venetian tragedy, Welles' Othello won the Palme d'Or at the 5th Cannes Film Festival. While it's difficult not to cringe at the actor/director's Blackface, there's much to enjoy about the unnerving picture whose visions haunt, whose sounds torment, whose performances shine a light on the turpitude of the Bard's treacherous characters. The cutting is especially feverish, rendering the action into a hallucination that frightens with its abrupt rhythms, so sharp they draw blood and dilacerate flesh.

Othello is streaming on Kanopy, Popcornflix, and Mubi.

MR. ARKADIN (1955)

Slurred remembrances and scary tales, countless lies and illusions weave a tapestry that recounts the story of an old world's devil. The erstwhile enfant terrible of Hollywood found a new home in Europe and European cinema, making some of his most interesting pictures there. Mr. Arkadin represents the oddest of these experiments, concerning itself with an elusive mystery man and the impressions he left on those around him. In many ways, it's Citizen Kane's Baroque twin, though even more beautiful with all its bilious toys and ancient rituals, desolate buildings open to falling snow, circuses of fleas, Gothic close-ups.

Mr. Arkadin is streaming on HBO Max, the Criterion Channel, and Kanopy.

TOUCH OF EVIL (1958)

Classified by many as the last great noir, Welles' first American film in a decade found him indulging in some of the most elaborate camera choreography this side of Soviet cinema. More than mere technical wizardry, the movie's an oily tempest of moral rot and decay, a typhoon of lost souls and Mexican ennui, grotesque performances by the main cast, and a scene-stealing turn by Marlene Dietrich. Beyond its verminous splendor, Touch of Evil works as a dark tragedy, sorrowful as much as it is beastly.

Touch of Evil is available to rent from most services.

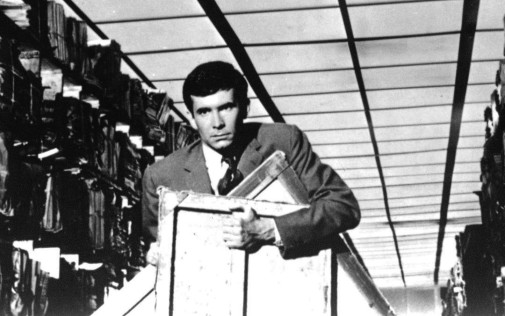

THE TRIAL (1962)

Welles' favorite from his filmography, this adaptation of Kafka's novel does the impossible. It successfully translates a seemingly unfilmable text to cinematic idioms that are as potent as the written word. Inspiringly disorientating, the picture drowns the viewer in bureaucratic absurdity, forlorn despair, existential dread. All odd angles and vertiginous sets, The Trial is oddly hypnotizing, like a creepy omen whose Wellesian abstraction beckons the viewer closer. The better to stab them with a blade of crystalized agony.

The Trial is streaming on the Roku Channel, Kanopy, and Fandor.

CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965)

My favorite movie based on a play by William Shakespeare is this masterful adaptation that binds together the Henriad, reconfiguring its perspective to center Falstaff instead of Prince Harry. Welles himself gives life to the eponymous drunkard, finding comedy in tragedy and grief in humor, dissecting garrulousness with sorrow, contrasting robust physicality with the subtlety of expression. Along the way, he delivers the greatest performance of his career as an actor, a monument of drama that's matched in perfection by the deep-focus photography able to turn kingly castles into cold caverns, a tavern into a merry tomb.

Chimes at Midnight is streaming on HBO Max, the Criterion Channel, and Kanopy.

THE IMMORTAL STORY (1968)

Simultaneously a love letter to the magnetism of Jeanne Moreau and an evisceration of the role of the storyteller, the filmmaker, this '68 flick produced for TV is a sour conundrum. Welles himself denied the picture was a meta-commentary, but it's hard to watch the narrative unfurl without meditating on the similarities between the on-screen manipulator and his off-screen existence. Regardless of such auteurism-based preoccupations, The Immortal Story still beguiles, its perverse plots making for a strangely melancholic tale.

The Immortal Story is streaming on the Criterion Channel.

F FOR FAKE (1973)

The last completed film of this master trickster is a trick in itself. Welles' love for illusions is laced through his cinematic inspiration to make a documentary(?) about forgeries, lies, and frauds. An essay film that doesn't let itself be bogged down by academisms, F for Fake is a merry lark. The movie's out to confuse the viewer, but it also wants to delight, inviting us to share in the fun of a genius filmmaker and amateur magician having the time of his life. By the end, truth, as a concept, has lost all its meaning, and cinema, as an art form, has been taken to new paradigms of creative madness.

F for Fake is streaming on HBO Max, the Criterion Channel, and Kanopy.

Apart from those titles, Welles also directed many shorts, some TV, fascinating making-of docs, and a plethora of unfinished projects. Out of those, I especially recommend his Filming Othello about the shooting the Palme d'Or winner, an intimate and sardonic look at the chaos of filmmaking that's as entertaining as it is instructive. Also, The Other Side of the Wind's on Netflix, an unfinished movie about an unfinished movie, an aborted return to Hollywood, and a nightmarish look into Welles' view of the American film industry that so thoroughly rejected him.

What's your favorite of Orson Welles' pictures? Aside from Citizen Kane, of course.