When she's good, she's very good. When she's bad, she's better.

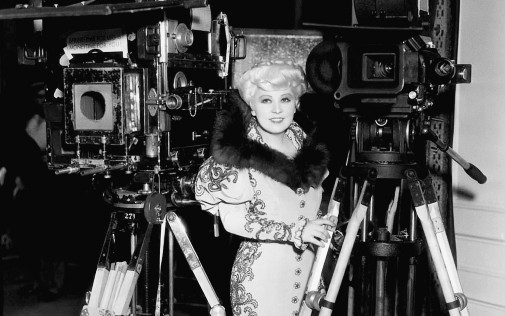

Mae West was one of the great stars of the Pre-Code era, though her reign as one of Hollywood's most popular queens was short-lived and curtailed by the advent of the Hays Code. Like Orson Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz after her, West was a target of William Randolph Hearst's ire. According to legend, the millionaire wanted revenge on West after she had made insulting remarks concerning the acting abilities of Marion Davies, his mistress. Such conspiracies are fun and it's easy to paint Hearst as Old Hollywood's perennial villain, but they're rarely 100% true. Mae West's fall from grace is more complicated than a vendetta from a mogul and a bunch of outraged Catholics. She was one of a kind, a symbol of licentiousness and indecency, a provocateur whose triumph was as amazing as it was temporary...

This month, the Criterion Channel has made available a selection of her movies. "The Best of Mae West" collection includes the diva's greatest successes, from 1933 to 1940, and offers a fascinating snapshot of a fascinating career.

Long before she first shimmied her way in front of movie cameras, Mae West was a sensation of the New York stage. Picking up dance moves and musical inspirations from the African American community, West created a vision of herself that became synonymous with unashamed sexuality, wanton abandon, and hedonistic ecstasy. More than anything, she knew her brand and how to commodify her persona, shaping herself into a character that's not too different from a drag queen. In fact, during the 1920s, she did work alongside drag queens. No wonder so many queer performers and impersonators love to play the camp icon to this day. Remember Alaska Thunderfuck's Snatch Game-winning performance on RuPaul's Drag Race All-Stars?

Still, to think of West's journey to fame as a steady meteoric rise would be erroneous. Her career was a succession of ups and downs, even before she came to Hollywood, always enmeshed in controversy and even some judicial battles. The play Sex was a bombastic success, for instance, but it did bring her a lot of trouble. Inspired by streetwalkers that West observed on the New York streets, the show was infamous, a polemic that proves that sex sells as does public outrage. Arrested on charges of corrupting the morals of youths with Sex, West paid her bail and managed to elude the puritanical authorities.

She was, after all, a moneymaking master and an expert in the art of serving audiences the right amount of bad behavior they craved. Take the fact many of her star vehicles were period pieces set at the turn of the century. Such a decision allowed West to indulge in the tight-laced fashions of yore, outlandish costumes that complimented her voluptuous figure in ways the 1920s and 30s draped fashions didn't do. Furthermore, West could frame some of her more risqué material in period finery, making it look safe by using and abusing, appealing to the viewer's nostalgia goggles. It was by way of one of those period exercises, the play Diamond Lily, that Mae West first encountered real big-screen glory.

At the dawn of the 30s, stage audiences started to get tired of West's shtick. She always essentially played herself and, like it would happen later in her story, repetition births exhaustion. In other words, the actress/writer/entertainment sensation was broke and in search of reinvention, which she found by starring in motion pictures. Through her friendship with Hollywood gangster du jour George Raft, West was cast in a supporting role in Night After Night. Outraged at the subpar quality of her lines, she refused to say them and, fed up, the studio told her to re-write the material herself. She did so and, when the film premiered, her brand of disreputable sexual provocation and silly wisecracks found new fans, turning West into a Tinsel Town star.

Her first leading role came with the adaptation of West's aforementioned play Diamond Lily into the movie She Done Him Wrong. Writing the screenplay and putting her foot down when it came to casting decisions, the actress made sure to solidify her brand in the new media of cinema and play to her strengths We can thank her for Cary Grant's stardom. It was in 1933's She Done Him Wrong and I'm No Angel that the British actor got his big break, his chemistry with West a marvelous marriage of opposites, of gentlemanly charm and a vixen's bodacious comedy. The two movies also became two of the top 10 box office earners of their year and She Done Him Wrong even conquered a Best Picture nomination. It was official, Mae West's arrival on the big screen as a colossal victory.

It's impossible to overstate how marvelously odd West's success was, even by today's standards. She was 40 in 1933, essentially becoming a world-renowned sex symbol at an age where most actresses unfairly get stuck playing matrons and sexless matriarchs. More than that, her image was built on a rare sense of female ownership over sexuality and desire, a shamelessness that still feels refreshing in 2020. Of course, such marvel was bound to attract negative attention, and the censors had a field day fighting against the licentiousness she so gladly exemplified. The men who would eventually create the infamous Hays Code were especially pestered about Mae West, her Pre-Code provocations incensing religious fundamentalists in raging fury against Hollywood, demanding censorship.

Hearst helped stoke the flames too. He was long opposed to West and, in the 1920s, had already made his newspapers publish outcries against the stage star's lewd creations. His opposition to her big-screen popularity was a continuation of that rather than a vengeful plot to defend the honor of Marion Davies. At first, Heart's fury had the opposite effect he desired, making Mae West's pictures even more sought after and talked about. However, things were soon to change for our beloved provocateur.

1934's Belle of the Nineties was filmed during a period of transition, from Pre-Code Hollywood to puritanical censorship, making it a strange animal, half-formed and neutered by heavy editing. No matter how many innuendos they cut, nothing could hide the figure of Mae West, covered in clingy metallic fabric, so tight you can see the closures of her corset and her nipples too. Nevertheless, the movie's quality was affected, its fangs ripped off, its jokes made sparse and arrhythmic. The following year's Goin' to Town suffers from many of the same issues, though West's charm is still in fine form. A canny avoider of censors, she quickly learned how to deliberately write scandalous passages into her films so that they would distract the censors from subtler bawdy humor.

1936's Klondike Annie, which saw West adapt to Hollywood's new morality, shows that strategy. It's one of her best movies, also featuring one of the actress' best performances. In that Raoul Walsh movie, West showed she had some versatility as an actress. She played the serious parts of the text with more nuance than her comedy ever showcased, finding depths of earnestness in her resolute defiance. Henry Hathaway's 1936 Go West Young Man further plays with the elasticity of West's persona, presenting her as a movie star fallen from grace whose trajectory is a sort of metanarrative commentary on what was happening off-screen. Still, the same jokes kept being recycled and, no matter how great West was, people were starting to get bored.

1937's Every Day's a Holiday turned out to be Mae West's first movie to lose money, though its splendorous visuals and farcical French accents make for an enjoyable romp. It was the last movie she shot in the 30s too. After seeing the dwindling earnings, West decided to reinvent herself once more and went back to Broadway to scandalize theatre-goers. In 1938 she was named box office poison along with a cadre of other big names, many still well known today like Joan Crawford and Katharine Hepburn. It seemed her time at the movies was done, finished.

In 1940, however, Universal Pictures tried to revitalize West's screen appeal with My Little Chickadee, a western comedy that paired her with W.C. Fields to great effect. Watching West shoot guns with the same nonchalance she seduces men is a bizarre pleasure. Nonetheless, West would only star in three more movies after that, finding better prospects as a live performer, singer, and comedienne. Her filmography is short but it's full of interesting pictures, morsels of jolly provocation whose openness about female desire remains revolutionary.

Are you a fan of Mae West's double entendres and bawdy brand of cheeky sex a