David Lean's film career is a rather peculiar thing. Before he ever sat on the director's chair, Lean was an editor whose resumé included collaborations with such lofty names of British cinema as Powell and Pressburger. It was during World War II that he started working as a director, adapting several Noël Coward plays and Charles Dickens novels. His early work was a cinema of über-Britishness, one that both celebrated, ravaged, and autopsied the idea of what it was to be British, taking an especially hard look at the effects of the war on society.

It's strange to consider that this master of the chamber drama, a director of modest style, would go on to become synonymous with the sprawling epics of the 1960s. Apart from some missteps, he'd be as wonderful doing these monstrously big movies as he was doing the small ones, but there's a clear dissonance of approach fragmenting the man's filmography. If there's a transitional piece to be found, a stylistic and thematic bridge, that explains how the humble adapter of prestige literature became the epic maker, it's 1957's The Bridge on the River Kwai…

You'll notice that, despite the introductory paragraphs, the title of this article centers Alec Guinness rather than David Lean. Both men would become Oscar champions thanks to The Bridge on the River Kwai, but it's the actor that's our object of study today. The reason to talk about Lean's career trajectory is that to fully understand Guinness' performance one must understand that The Bridge on the River Kwai is a study on arch-Britishness, of militarism giving into obsession and craziness. Lean takes the themes of his early days and explodes them into a wider canvas, one that allows him to exaggerate and distend, to make the subtext into text.

A film like 1944's This Happy Breed is as much about the war as the 1957 Oscar victor, but its milieu is domestic. In such a work, the war manifests itself in psychological hauntings since combat is necessarily distant. The Bridge on the River Kwai, as a war epic, seems more predisposed to represent the literal scars of the conflict, the battle, and the carnage. However, Lean maintains his psychological investigation even when the thrill of violence is available to him, effectively anchoring the latter film in character studies. The images may be epic, but the story and its tragedies live in the realm of the mind like in his old films.

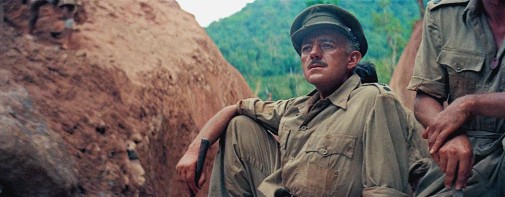

Alec Guinness is the perfect embodiment of his director's approach. He's Lean's intentions made flesh, a ghost of British militarism whose devotion to the concept of honor drives him to the edge of madness. Guinness is Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson, a dutiful officer that surrenders to the Japanese, becoming a POW under the authoritarian order of Colonel Saito. The two men are mirror images of Imperial Jingoism, each one chained to their nation's ideal of warmongering masculinity. They're prideful and they're slaves to order, creatures whose stubbornness far exceeds the limits of sanity.

Nicholson starts the film as an obstinate prisoner, demanding that the Japanese respect the dictums of the Geneva Conventions, risking torture and great suffering while always maintaining his dignity. However, has the narrative unfolds, the shrill pride of this gentleman officer starts to corrode reason. When his men are tasked with building the titular bridge, Nicholson, whose regimental norms dictate that he should obey the Japanese, decides that they will not only build it, but they will build it better than their enemies ever could. The bridge soon becomes a monument to the Lieutenant Colonel's arrogance, a near treasonous feat that stands as a symbol of British exceptionalism driven to self-destructive extremes.

To watch Guinness play the gradual twisting of Nicholson's mind is to see Lean's cinema mature into its iconic grandiosity. Early on, there's a brittle quality to the actor's work, an affected manner that suggests a loving caricature of British respectability. It's as if the performer is weaponizing his own screen presence, purposefully highlighting the archness of the role and underplaying its interior chaos. However, as the negotiations with Saito turn ever more perverse and the bridge takes hold of Nicholson's will, the folly of the man starts to show through. His politeness and sense of duty, his want for dignity, sour into something grotesque. He becomes a man blinded by authority, by the need to prove his excellence and valor even if it may cost the lives of his allies.

Alec Guinness never overplays Nicholson, maintaining a foot firmly planted in the land of psychological realism. However, while his performance might have seemed too small for an epic at the start of the movie, by the end, the screen is nearly incapable of holding the self-respecting lunacy the actor irradiates. When the climax arrives, Guinness isn't so much playing a man as he is playing a body possessed by the demon of obsession. That's especially evident because, moments before the end, Nicholson wakes up, a wave of self-awareness exorcizes the folly and he confronts what he's done. Guinness plays the shift with blanched panic, deflating before our eyes.

British jingoism thus implodes onscreen, personified by a crazy man who's forced to acknowledge that he was wrong, that he has become a monster. It's a miraculous bit of acting, one that works symbiotically with the movie and articulates, with gestures and dialogue, what David Lean was doing behind the cameras. I'd go as far as to say that it's one of the greatest performances ever honored with a Best Actor Oscar, the pinnacle of Alec Guinness' craft, and one of the best cinematic representations of the poisonous influence of obsession.

The Bridge on the River Kwai is available to rent from Amazon, Apple iTunes, Google Play, and others. Go see it and tell us if Alec Guinness was a just winner of the Best Actor Oscar of 1957.