Daniel Walber's series on Production Design. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

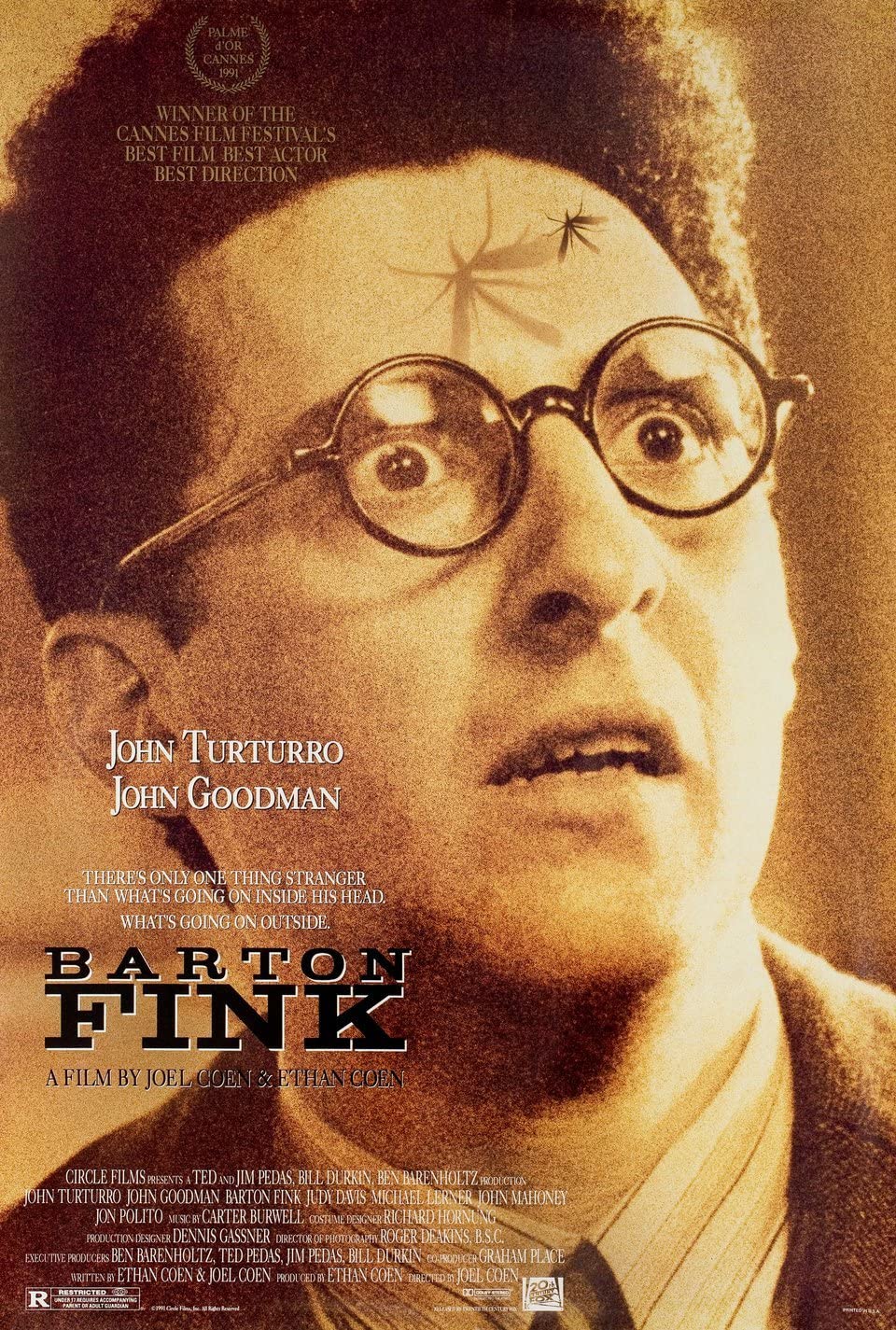

What is the wallpaper of the Common Man? It’s a strange question, but Barton Fink is a strange movie. The titular writer (John Turturro) is a man consumed by passion for the clichéd unsung hero, though he would never go so far as to actually ask a Common Man what he thinks. His obsession is really with the idea of the Common Man, abstract and waiting to be tossed onstage or slapped onto the blank canvas of a movie screen.

What is the wallpaper of the Common Man? It’s a strange question, but Barton Fink is a strange movie. The titular writer (John Turturro) is a man consumed by passion for the clichéd unsung hero, though he would never go so far as to actually ask a Common Man what he thinks. His obsession is really with the idea of the Common Man, abstract and waiting to be tossed onstage or slapped onto the blank canvas of a movie screen.

In his defense, the Common Man was not yet a cliche when Fink arrived in Hollywood, sometime in 1941. Henry Wallace’s famous “Century of the Common Man” speech wouldn’t be delivered until May of 1942, inspiring Aaron Copland to write his “Fanfare for the Common Man” soon after. Maybe someday the Coen Brothers will make a sequel, and Barton will take the opportunity to claim credit for both of those cultural landmarks.

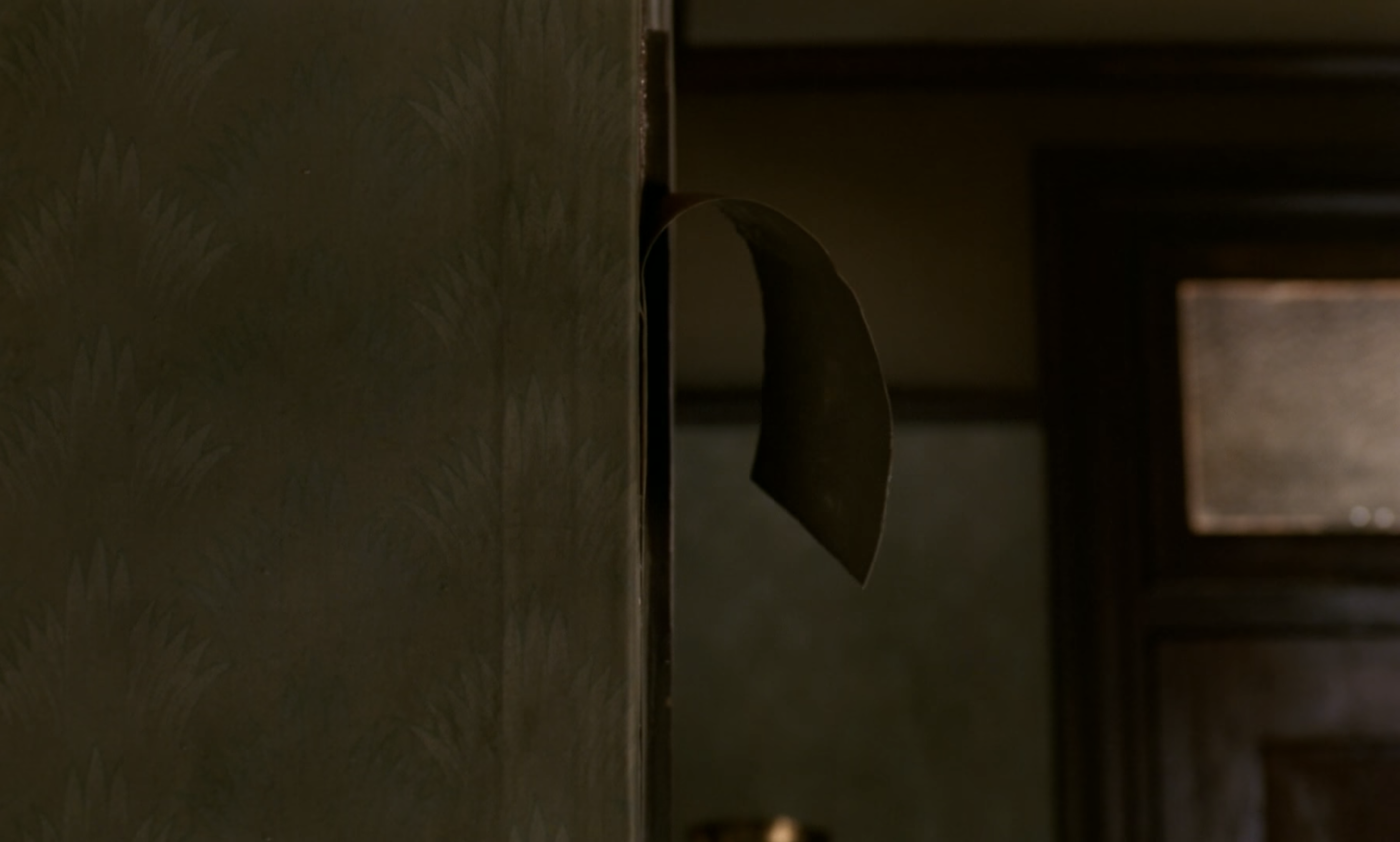

But back to wallpaper. Barton Fink opens with a close-up of it, a pleasant sort of floral-Deco pattern in mild colors...

As it turns out, it’s the wallpaper on stage for Barton’s Broadway debut. The play is a social realist drama about something, presumably, though we only hear the end of it - and the last few lines of dialog would fit just as easily into a Clifford Odets play as it would Home for Purim. The rest of the stage is fairly nondescript, a basic arrangement of armchairs and lamps that could be reused by a different theater every season for the next 50 years.

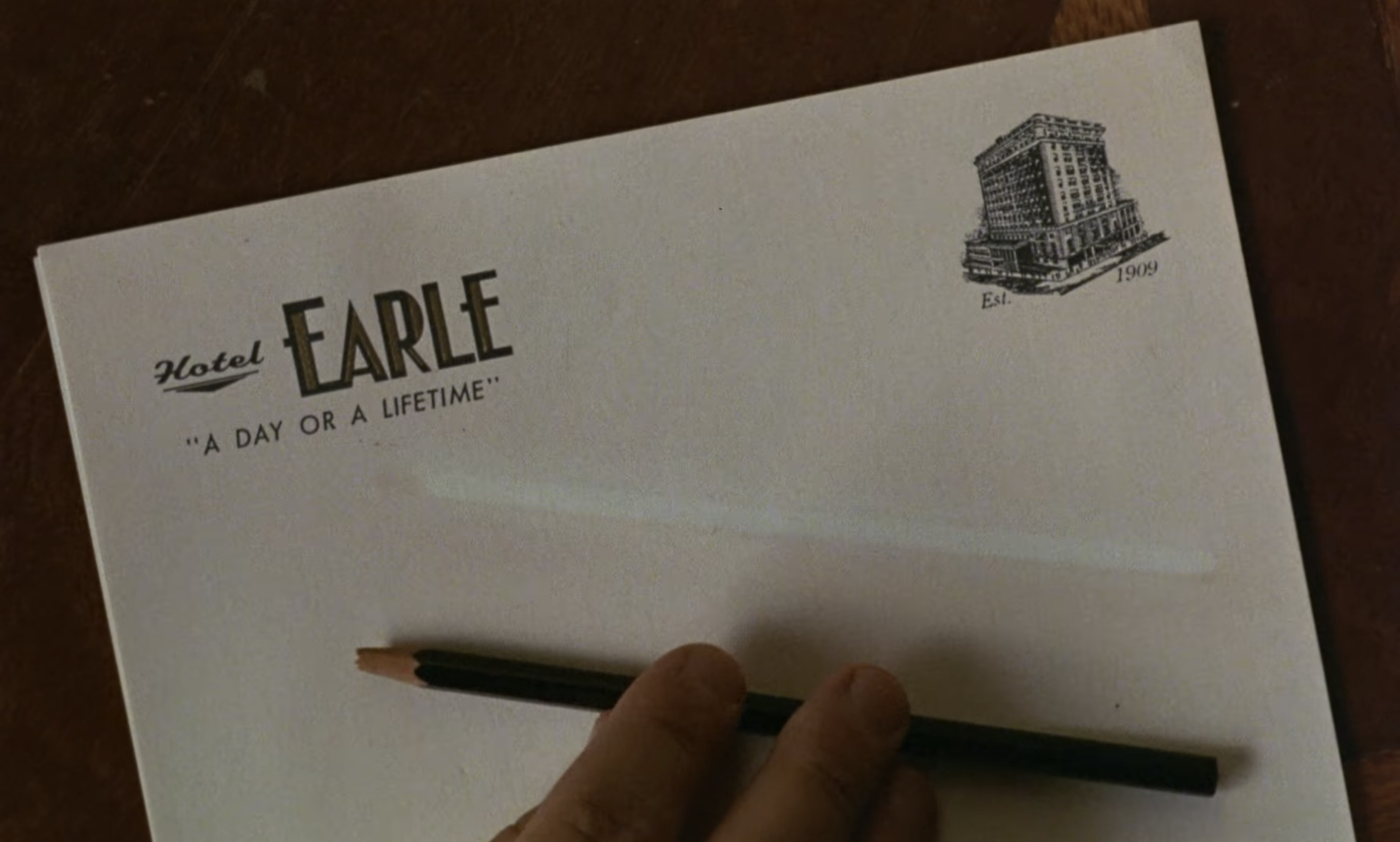

In a whirlwind, Barton’s instant success on Broadway turns into a Hollywood studio contract, and he suddenly finds himself checking into a hotel in Los Angeles. Not one of the big, fancy ones that you’ve heard of, mind you. He goes right for the Hotel Earle, an obscure fleabag that he presumes will keep him in touch with the “Common Man.”

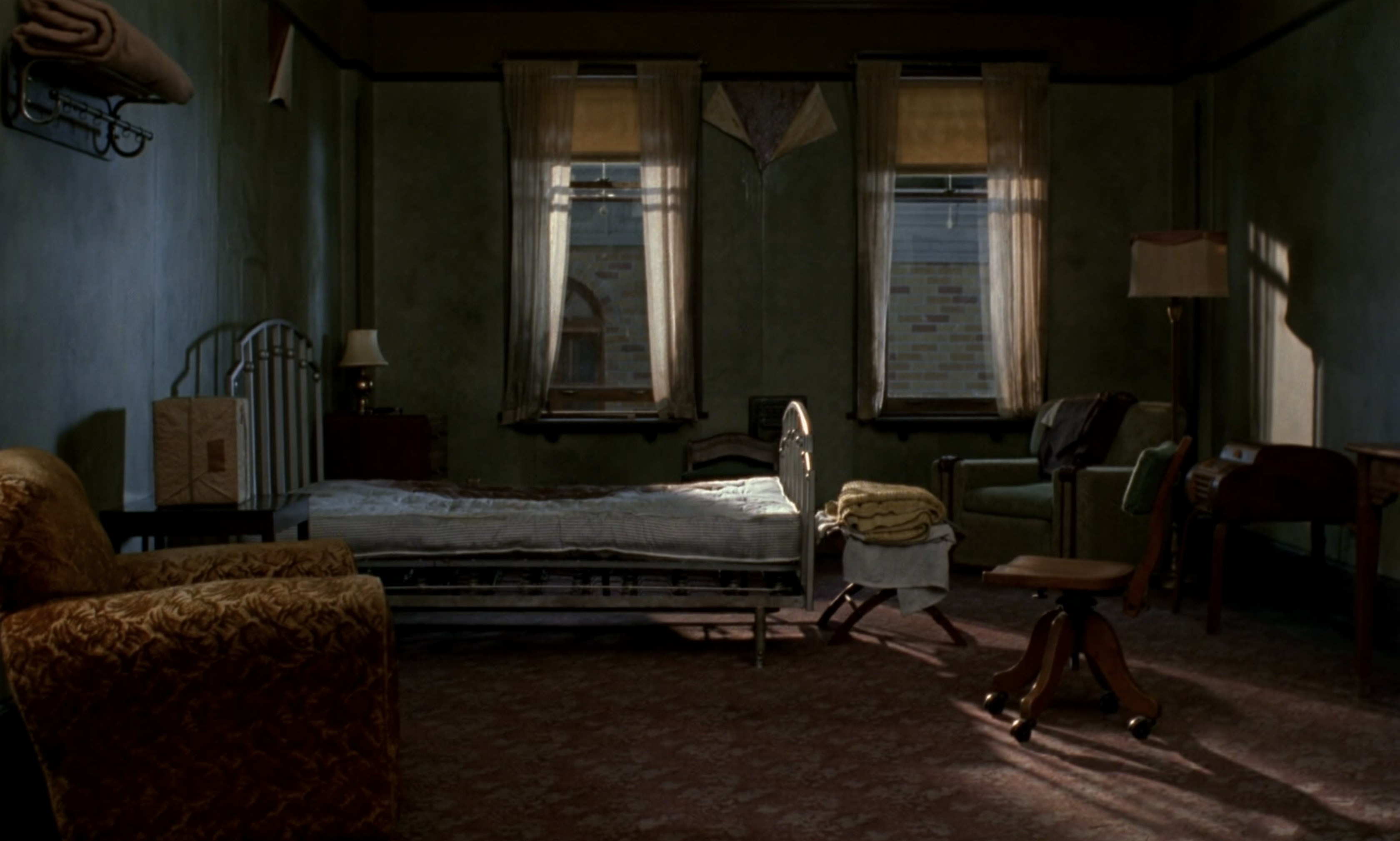

And, in a sense, the Earle delivers. Its lobby is full of the same lamps and lumpy armchairs, though in more tropical colors. The biggest difference is the presence of towering plants, the only sign of lush life in this otherwise dismal atmosphere. It’s the same humdrum Fink fantasy of Americana, just hotter and damper.

Chet (Steve Buscemi) registers Barton at the front desk and sends him upstairs. His room doesn’t look too bad, to be honest. The biggest problem is that everything seems to be covered in a thin layer of dust, including the truly ominous stationary. The Earle’s sloga, “A Day or a Lifetime,” reads like a threat.

But the truly remarkable thing about this hotel room is something that you might not notice, at least not the first time around.

It’s the same wallpaper! In a different color, sure, but that hardly matters. Frankly, even the pretence of naturalism falls away the moment this pattern gets its second close-up. It may seem like a small thing, but it’s a brilliant way for the Oscar-nominated design team (Robert C. Goldstein, Leslie McDonald & Nancy Haigh) to slowly chip at the fabric of reality. And this is before it starts to peel off the walls.

Here’s the thing about wallpaper: these days, there are all sorts of adhesives you can use to put it up. There are clay-based wallpaper pastes, pastes with anti-mold chemicals, synthetic resin-based glues, etc. But before the 1950s, nearly all wallpaper in America was stuck to the wall with wheat paste - which, as it sounds, is made with regular old wheat flour.

And while this is still a totally reasonable DIY way to stick up some posters, it can present problems. In 1901, New York State went so far as to outright ban the layering of new wallpaper on top of old. Why? The thicker the wall of paste, the more tempting a snack it is to cockroaches and all sorts of other pests. And that’s without whatever is happening at the Hotel Earle, which seems to have the internal climate of a hot bog.

Chet sends up some thumbtacks, which would honestly not be a horrible idea if the problem were only one particularly weak panel. But by the time Barton’s life is really falling apart, so is all the wallpaper. The Hotel Earle isn’t an “authentic” abode of the “Common Man,” it’s a soggy, self-serving fantasy that threatens to fully ingest both Barton and his fraudulent life’s work.

Perhaps the strangest thing about this is the distinct impression the Hotel Earle isn’t actually at risk of collapse. The flames seem almost cosmetic, a temporary flare-up brought about by Barton’s own folly. Eventually the fire will burn itself out, Chet will put up another layer of wallpaper, and some future unlucky guest will check in. The Hotel Earle, like Hell, is apparently fireproof.

Previously on the fourth season of The Furniture

- The Golem (1920)

- The Battle of Neretva (1969)

- Safe (1995)

- Frida (2002)

- Joan of Arc (2019)

- First Cow (2020)

- Shirley (2020)

and... - first three seasons, an index