By Glenn Dunks

The Criterion Channel recently added a whole bunch of Australian movies from well-known directors like Peter Weir, Gillian Armstrong and Phillip Noyce onto their service. While some titles from the “Australian New Wave” series were (I think?) already on there, there are many that are not only new to the service but new to American streaming full stop.

The Criterion Channel recently added a whole bunch of Australian movies from well-known directors like Peter Weir, Gillian Armstrong and Phillip Noyce onto their service. While some titles from the “Australian New Wave” series were (I think?) already on there, there are many that are not only new to the service but new to American streaming full stop.

The series features 21 titles that range from 1971 to 1982, several of which are stone cold masterpieces. In a funny little merging of cinematic timelines, a few of these movies have more historically been ignored by the prestigious banner of the new wave era as their genre elements meant they often get lumped less nobly into the “Ozploitation” sidebar of exploitation, sex comedies and horror movies. Whatever it took, however, I’m happy to see some of my favourites find a streaming home internationally.

Now if only Criterion would add more of them to the damned collection!

I thought it would be fun to list the titles—because who doesn’t love a list?—but base it not on their quality. Rather, how much they speak to Australia, the country, the people, and its identity both then and now as we look at them nearly 40 years removed. Subjective, of course, and it's been many years between viewings of many of these, but I feel if you want an education on Australia, then there are some films here that would do a better job than others...

21. Money Movers (1978, Bruce Beresford)

This gung-ho heist thriller is a rip-snorter of a good time. Something of an Australian Heat if you want to be comparative, with cinematography by future Oscar nominee Donald McAlpine (who as well as Moulin Rouge! was behind the camera of a bevy of iconic Hollywood blockbusters in the ‘80s and ‘90s).

20. The Getting of Wisdom (1977, Bruce Beresford)

There is a surprising queer streak running through this era of Australian cinema, whether deliberate (this one, for instance) or not (Gallipoli, depending on who you listen to). This one is an 1890-set period drama at an all girls’ college (yes, there are multiple films with that setting on this very list) about a girl who wants to grow up to be a great writer (ditto).

19. Long Weekend (1978, Colin Eggleston)

Environmentalism has been around in movies for a while now including quite prominently in this twisted 1978 horror movie where nature decides to take revenge on a pair of bickering marrieds on a camping retreat. Try to avoid the 2009 remake with Jim Caviezel.

18. Walkabout (1971, Nicolas Roeg)

Sometimes foreign directors can paint a picture of Australia that one our own just can’t—most famously Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright. However, Roeg’s blend of Indigenous rite of passage and white survivalism has always felt to me as if it was too enamoured with exoticizing the idea of David Gulpilil and that it’s entirely international creative crew don’t have anything to actually say about this country. But it has been so long, I’m open to being convinced.

17. The Plumber (1979, Peter Weir)

Other movies have more gruesomely repurposed the image of the Aussie bloke to that of a man of menace (see Mad Max down the list as well as stuff like Wolf Creek). Weir did something similar albeit less blood-splattered in this much more mundane domestic comedy thriller. Made for TV, which explains the drab production values for a Peter Weir film.

16. The Year of Living Dangerously (1982, Peter Weir)

The only Oscar winner on here (for Linda Hunt’s performance as Asian man Billy Kwan; yes, it’s problematic as much as it is audaciously gender-blind) and a reminder that before he was an openly horrible human, Mel Gibson was such a pleasure to watch. Set in Indonesia during the 1965 revolution, this was Weir’s final movie that felt truly Australian (his Enya biopic Green Card is technically an Aussie production, but that's a technicality). A rare film that positioned us as more than just spectators in the greater Asian region.

15. Storm Boy (1976, Henri Safran)

Meet Mr. Percival, the most famous pelican in the world. It sadly remains rare for young Australian audiences to hear Australian accents in films—television is better, but radically vanishing. So it’s impossible to state the importance of Safran’s film on multiple generations for whom Storm Boy was not just a childhood classic, but also likely their first experience of Aboriginal culture (the education system’s ignoring of First Nations’ culture is not unique to one part of the world, sadly).

14. Starstruck (1982, Gillian Armstrong)

Armstrong followed My Brilliant Career by running squarely in the opposite direction with a boldly over-the-top musical that’s part pub singalong part Top of the Pops. Starstruck walked so that Strictly Ballroom, The Adventures of Priscilla and Muriel’s Wedding could run a full decade later. I have the soundtrack on vinyl and it’s an experience. The whole thing is an experience.

13. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975, Peter Weir)

Look, the last thing the world needs is another list about Australian cinema putting Peter Weir’s iconic St. Valentines Day mystery in the top spot. And while I, too, would probably list it as my favourite Australian film, there’s a reason why it was and continues to evoke European cinema. But while Weir’s spellbinding turn of the century film takes much of its menace from its landscape, it has a lot to say about Australian society’s response to the sexuality of women and their position within turn-of-the-century society and beyond that remained relevant in ’75 as well as today. I really enjoyed the recent mini-series, too, which was like a pimped up version and decidedly its own beast.

12. Don’s Party (1976, Bruce Beresford)

Any excuse for a piss up was long the Australian way. Societal norms are put under a microscope as they crumble on the night of a federal election party. A uniquely Australian take on 1969 and the generational changing attitudes to sex and politics that’s easily the funniest film on the list.

11. The Last Wave (1977, Peter Weir)

I’m not sure if its portrayal of Aboriginal culture is considered offensive or not (I suspect yes, although it’s hard to find Indigenous writings on the subject). But unlike, say, Walkabout, I find Weir’s film—a big swing of a genre-tinted legal thriller (what a combo!)—far more interested in the way black and white cultures interact in Australia, their inherent differences, and how racist attitudes continue to manifest in ever-evolving ways that suggests we'll never truly overcome them.

10. Puberty Blues (1981, Bruce Beresford)

Australian surf culture gets skewered in this refreshingly frank portrayal of teenage life that takes its central female characters as seriously as its audience deserves.

9. The Devil’s Playground (1976, Fred Schepisi)

I wouldn’t necessarily expect a film set on the grounds of an all boys’ catholic school to so fully represent sweeping changes that had come and would continue to eventuate in Australia. And yet Schepisi’s debut film about the conflicting push and pulls within those walls really does stand for so much of Australia’s history with its identity both broadly (stifling traditionalism) and specifically (our rather curious relationship to religion). The TV miniseries sequel (with a small role by Toni Collette!) from 2014 is also recommended.

8. and 7. The Cars That Ate Paris (1974, Peter Weir) and Mad Max (1979, George Miller)

8. and 7. The Cars That Ate Paris (1974, Peter Weir) and Mad Max (1979, George Miller)

Cars, cars, and more cars. Australia as the home of the hot-tempered auto grunter certainly bears out in movies, but I love how wildly that manifests itself across these two distinctly different movies. One a strange satire of small-town survivalism and the other a ragged propulsive thriller (filmed partially in my hometown!). And, yes, Miller was inspired by The Cars That Ate Paris (aka The Cars That Eat People) for Fury Road’s echidna car.

6. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978, Fred Schepisi)

Australia was—and continues to be—a very racist country. Star Balang Tom E. Lewis passed away recently, but this debut performance shows why he remained one of the country’s finest actors for four decades.

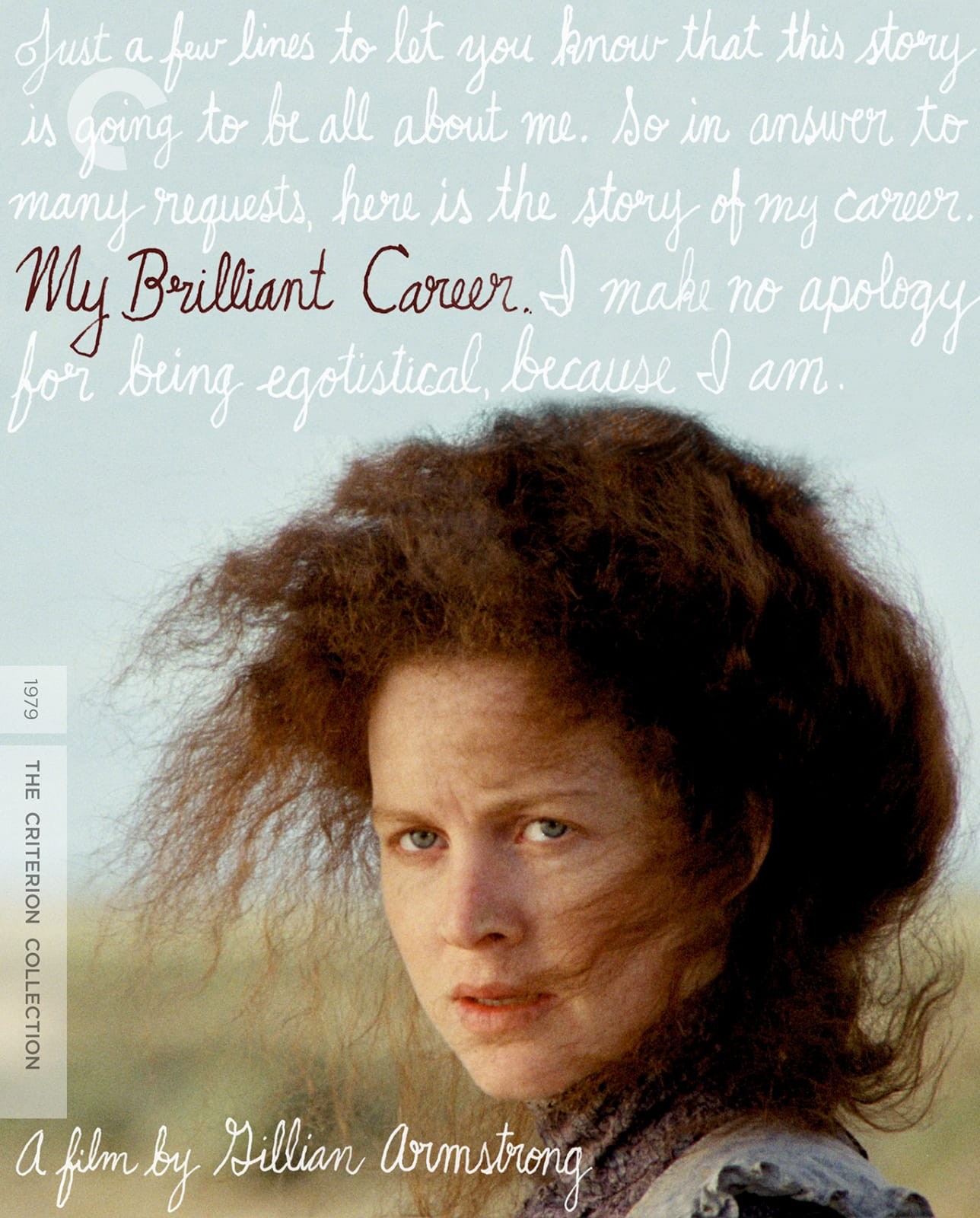

5. My Brilliant Career (1979, Gillian Armstrong)

This genius work of sublime filmmaking with Judy Davis and Sam Neill, feels so Australian for the very reasons that it goes against the grain of what so many see as defining of Australian cinema. Within its already surprising femininity, it twists the idea of a period romance with a lead character who desires more despite her outwardly station in life.

4. Sunday Too Far Away (1975, Ken Hannam)

As you have seen, in the 1970s as our national cinema was just re-emerging after many decades of near total silence, filmmakers like Hannam were looking back at the idea of what makes a country and what makes a nationality, unsure of finding it in the present day. And like most countries I can think of, Australia is one built on back-breaking workers.

3. and 2. ‘Breaker’ Morant (1980, Bruce Beresford) and Gallipoli (1981, Peter Weir)

Beresford’s is the better film (an Oscar nominee and a Cannes winner, too) but Weir’s is the more famous. Both directly anti-war, and like many of the films of this list, both wrestle with Australia’s place within the commonwealth and the world, while building our ‘identity’ through imagery that perseveres to this day. Weir’s Gallipoli has arguably the most famous single shot in Australian film history. If you've seen it, you know the one.

1. Newsfront (1978, Phillip Noyce)

Like Sunday Too Far Away, Noyce’s masterful Newsfront looks back to a time when Australia was building itself up out of the monarchist shadow post-war, asserting a unique identity carved from the remnants of WWII. Part of the genius and its cinematic power here lies in its setting among the newsreel industry, which for many was the first time seeing the nation and their fellow Australians on screen. In fact, the first Australian film to ever win an Oscar was a newsreel (Kokoda Front Line! for Best Documentary in 1942) so its history runs deep. Noyce's film usually runs a close race with Picnic at Hanging Rock as my favourite Australian film because it's not only a bloody good yarn (here I am slipping further into colloquial slang), but for that extremely Australian perspective. I love it.

Further viewing: They’re not on the Criterion list and so their availability may be questionable, but I don't think any discussion of Australian cinema during this period can ignore Wake in Fright, which is every bit as brilliant as its reputation suggests. Michael Thornhill's The F.J. Holden is a wonderful more down-to-earth examination of car culture. Carl Schultz's Careful He Might Hear You and Donald Crombie's Caddie fully deserve to be spoken about alongside My Brilliant Career as powerful, worldly films about female ambition and drive placed in context with class. And while it's hard for local films to build reputations these days, I swear every time anybody watches Tom Cowan's Journey Among Women and Tony Williams' Next of Kin, their standings rightfully grow.

You can find a relatively exhaustive list of Australian films of the 1970s and the 1980s that I curated on Letterboxd.

Visit the Criterion Channel to stream them all.