Sean Donovan looks at two films from NYFF's "Revivals" section...

The major film festivals of the world, New York included, take as much responsibility for cinema’s past as its future. Alongside new hyped arthouse projects, festivals program curios from the past that may have fallen through the cracks or not received their due recognition in their day. In other instances, festivals re-deploy older films to the contemporary moment in an act of deliberate commentary, the film speaking to culture in a way that feels freshly vital for 2020 (that is certainly the case of one of the selections profiled here). Over the past weekend, New York Film Fest virtual cinema uploaded two of their revival selections, Joyce Chopra’s Sundance-winning drama Smooth Talk (1985) and a Blaxploitation cult film The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973). Both are canny, fascinating picks from the NYFF, and well worth the revisit in 2020...

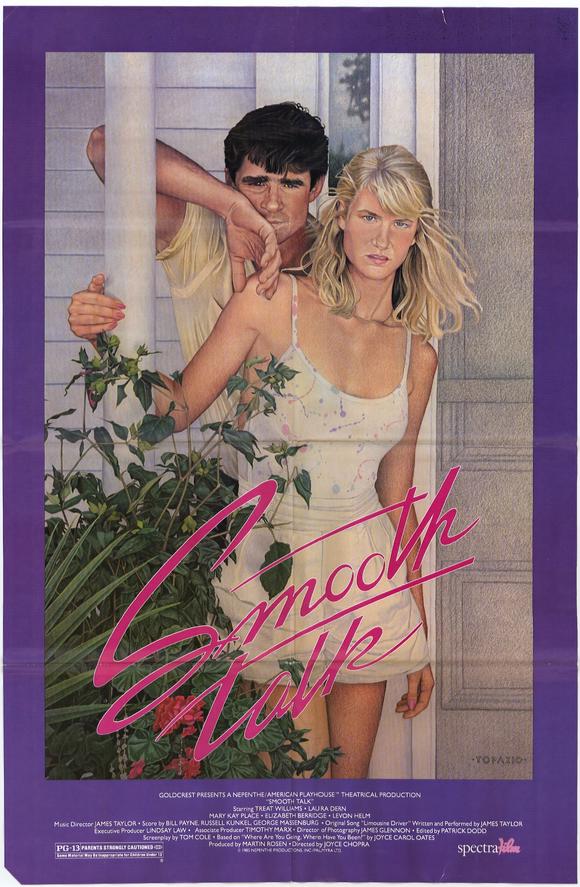

Smooth Talk is the ideal revival section pick: at once totally of its time, yet bracingly fresh in chosen moments. A then little-known Laura Dern has the starring role of Connie Wyatt, an energetic teenager eager to go out with her friends, party hard, and live life to the fullest against the wishes of her more pragmatic, exhausted mother (Mary Kay Place, terrific). And though the festival’s bill of the film, and its plot summaries online, emphasize her eventual collision with a mysterious stranger Arnold (Treat Williams), it’s important to emphasize that Dern’s Connie commands the screen for the vast majority of the film. We watch Connie try on outfits and new identities for her friends around town, and we watch her modulate her relationships with her increasingly irritated family, frustrated with Connie’s burgeoning desires for … something. That ‘something’ is kept purposefully vague, sexual and hormonal but also far-ranging; Connie wants a full-scale transformation. By the time Arnold enters the narrative whispering “your daddy’s house is just a box, a cardboard box. There’s nothing for you” he’s speaking to someone already ready to jump ship.

Laura Dern has made a brand of playing women desperate to be transformed by their passions, whether it’s Ellie Sattler’s fervent love for dinosaurs, Amy Jellicoe’s radicalization in Enlightened, or whatever her multiple blurring, frenzied characters want in INLAND EMPIRE. It’s fascinating to see these seeds of her masterful genius so early on in her career with her wild-eyed performance of Connie, gangly and awkward in all the best ways, lunging at passion wherever she can find it. I can’t overstate how fun it is to watch a teenage Laura Dern run around shopping malls, being too loud with her friends, and oogling boys’ ‘buns’ (the word ‘buns’ gets a thorough, inexplicable workout in this film). This is all scored to some of the cheesier tunes of the James Taylor songbook, the ones too permanently retro to grace easy listening radio stations; an atmosphere of bizarre 80s normcore bliss.

Smooth Talk displays a surprising tonal elasticity. One moment this is a kitschy 80s throwback, the next the film shocks with its emotional immediacy. Dern radiates vulnerability in tense scenes with her mother- she quietly says “I know, you don’t like my hairspray” to her mom, anticipating a fight that made my heart break. Even cheesy old James Taylor gets in on the action: in one of the film’s most moving moments Dern gives a brash performance of “Handyman,” singing along to the radio, while her mother silently mouths the words and sways in the next room, unbeknownst to her daughter. Grace moments like these are in high supply thanks to the tender and intricate work of Joyce Chopra, a director primarily for television, whose lack of other films is a reminder of the lack of industrial support women directors received and continue to receive in Hollywood. Smooth Talk works in these two registers: one the precious emotional drama, the other an almost camp explosion of kistchy energy. Get you a film that can do both!

Arnold’s entrance into Smooth Talk brings with it a graver tone, summoning a distinctly 1980s moralism equating sexuality with death and danger. A suburban conservatism is baked into the film’s DNA, yet even this is bizarre and unexpected in its representation, leaning into surrealism with an almost biblical sense of stakes. And it’s beautifully played by Dern, with an intensity steeped in the boundaries between the suburban and the unknown that led me to wonder if Smooth Talk is a lost node in the mythology of David Lynch. In the film’s brief 1985 release, was one of the few attendees Lynch himself, leading him to cast her in Blue Velvet and many years later protest alongside a cow for her rightful INLAND EMPIRE Oscar nomination? You could hardly find a better text for Laura Dern worship, the actor’s magnetic openness already a finely tuned instrument. A-

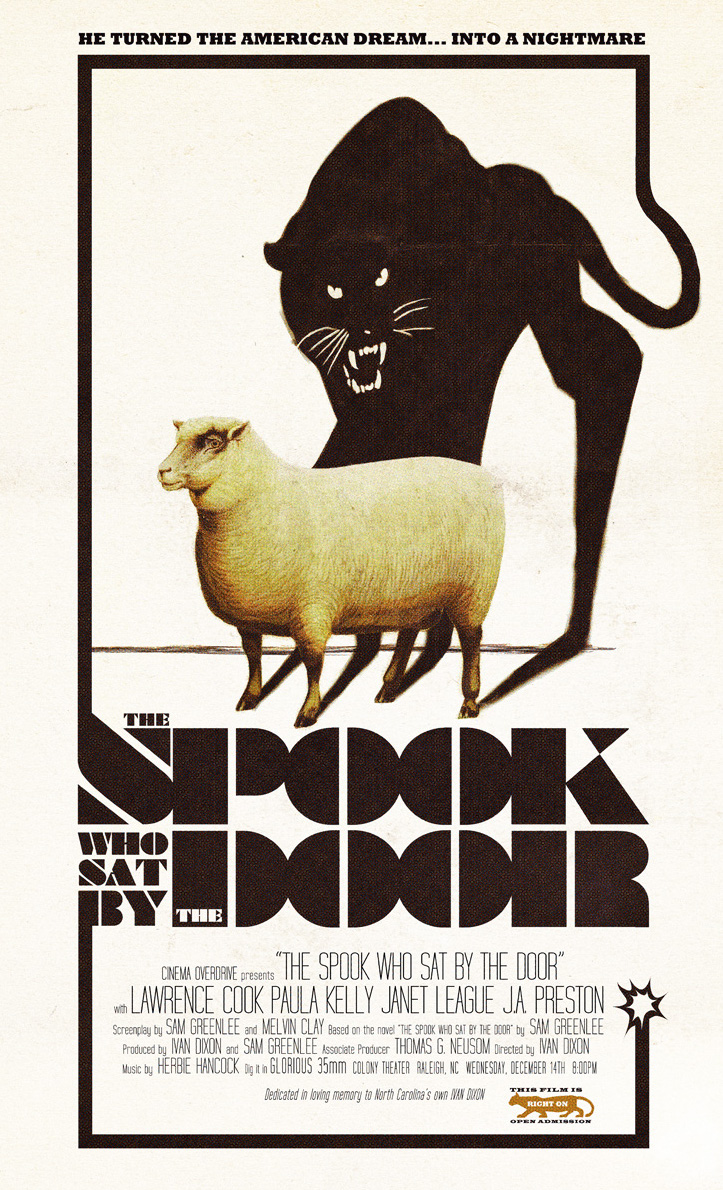

The Spook Who Sat By the Door, a blaxploitation political thriller from 1973, was not a selection by the New York Film Festival’s programming committee, but rather one of this year’s honored directors, Ephraim Asili, whose film The Inheritance opened the ‘Currents’ section of the festival. Asili selected The Spook Who Sat By the Door, citing it as a thematic and stylistic inspiration, and equally, a worthy stretch to the criteria of what is deemed ‘art cinema’ at the New York Film Festival. The film follows Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook), a black man recruited by the CIA to solve the image crisis of an all-white department, who ends up taking his training in warfare techniques and physical combat to a guerrilla group the ‘Freedom Fighters,’ made up of young black men from Chicago. Tensions between the Freedom Fighters and the US government escalate into an action plot rich with espionage, subversion, and radical liberation.

Blaxploitation was always political, creating black stars and some black directors with energetic films that refused any sense of humble respectability politics, or a concern with maintaining ‘positive images’ of black people for white audiences. What is unique about The Spook Who Sat By the Door is the literal surface-level representation of these dynamics, in a film quite literally about organizing against a white supremacist state, and laying out the tactics and coordination needed to get there. Whereas more familiar Blaxploitation classics like Shaft and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song tell this story through style and genre elements, Spook Who Sat By the Door has a seriousness of purpose that is fascinating, and clearly a reason why it was heavily censored from theaters in the 1970s. The Spook Who Sat By the Door’s embrace of radical black liberation politics was not unprecedented for its time, but its manner of address is; the film’s finely engineered screenplay weaves an astonishing array of civil rights topics (tokenism, colorism, passing, blackface, police brutality, activist power hierarchies, the conflict of black cops) completely organically.

Films like these are notable not for being ‘ahead of their time,’ but as a reminder of the work black artists have done for generations of American filmmaking, in service of narratives that re-claim black sovereignty within a racist culture. If the film is let down slightly by under-drawn characters and limited acting, it’s only because its agenda was so far-reaching to begin with, with mountains of ambition and energy creating an anti-CIA black liberation spectacle that demands thoughtful re-consideration by current audiences. B+

The Spook Who Sat By the Door is "sold out" (how does something sell out virtually, we don't quite understand this but all the festivals are now doing it) but Smooth Talk is still available to screen virtually. It runs until 09/24 at 8 PM EST.