"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

Ten movies were nominated for Best Production Design at the 1965 Oscars, one of the last years before the Academy retired separate categories for color and black & white. There are some striking examples on the list, from the bloated (The Agony & the Ecstasy, Ship of Fools) to the bizarre (Inside Daisy Clover). But when you come down to it, there’s really no looking past Doctor Zhivago.

Ten movies were nominated for Best Production Design at the 1965 Oscars, one of the last years before the Academy retired separate categories for color and black & white. There are some striking examples on the list, from the bloated (The Agony & the Ecstasy, Ship of Fools) to the bizarre (Inside Daisy Clover). But when you come down to it, there’s really no looking past Doctor Zhivago.

This was David Lean’s second consecutive film to win the category, after Lawrence of Arabia three years earlier. While their visual scope is similar, the two films actually have very different preoccupations. Lawrence of Arabia is about a man determined to shape history. Doctor Zhivago is about a man trying to escape it. Understanding the difference helps us understand the design.

We begin on the eve of the Russian Revolution, a moment of great social contrasts...

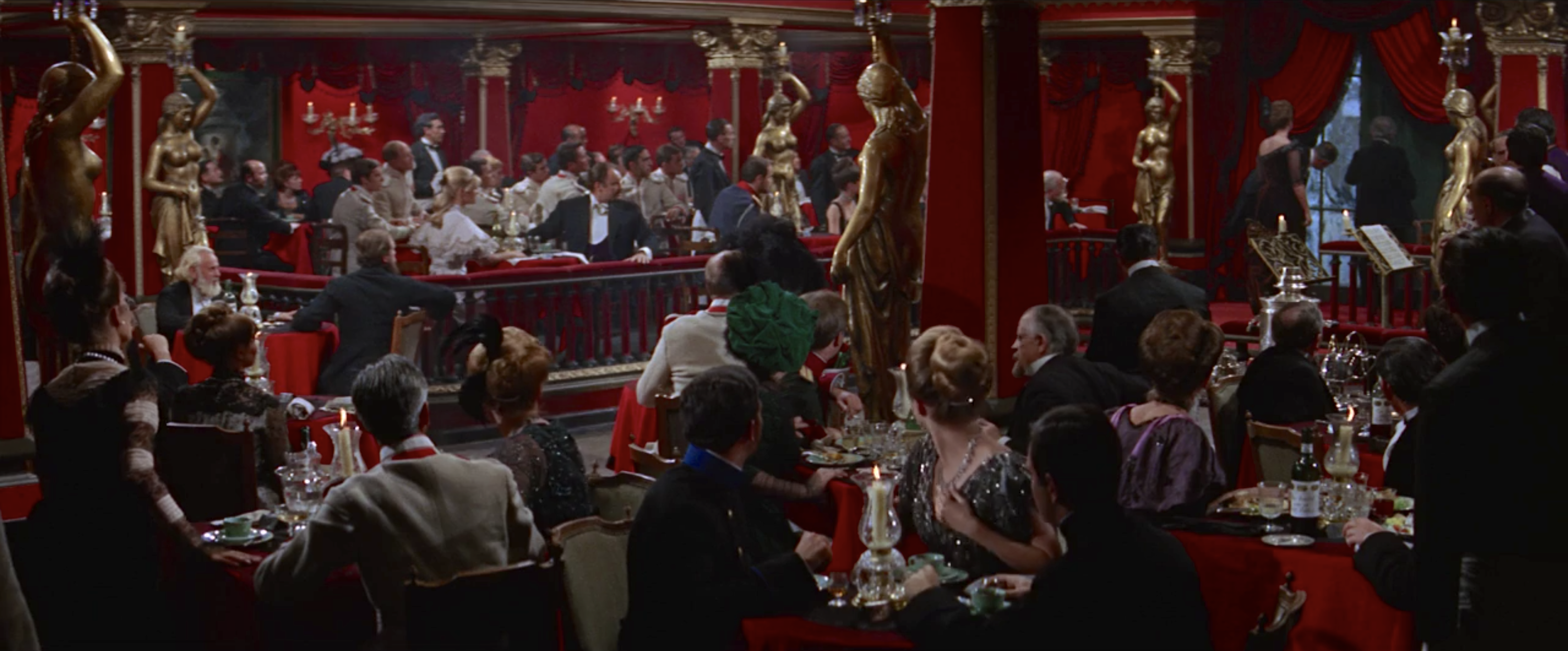

The team led by production designer John Box, art director Terence Marsh and set decorator Dario Simoni (all of whom also worked on Lawrence of Arabia) doesn’t attempt subtlety, but they do avoid a simplistic telegraphing of color. The banners of the Bolsheviks marching down Moscow’s streets are bright red, but so are the interiors of the most aristocratic restaurants.

Cloaked in velvet and overseen by a pantheon of Grecian statuary, these spaces project an assertive tackiness. Komarovsky (Rod Steiger) and his ilk scheme across the gambling table, their cards dimly lit by an array of expensive-looking light fixtures.

Yuri Zhivago (Omar Sharif) has spent much of his life traveling in and out of restaurants just like this one, but he is clearly more comfortable in less sinister displays of opulence. The house of his adopted family, the Gromekos, is an unassuming palace of muted browns. Bookshelves line the walls and tasteful lace is draped over every chair.

All of these interiors feel stuffy, low ceilings over carpeted floors. This makes a clear contrast with the impending revolution, threatening to throw open the windows and let in the whirlwind. The street, after all, has no roof at all. But there are also a couple proletarian interiors, such as this enormous cafeteria.

Remarkably, Yuri seems equally comfortable, confident and compassionate everywhere he goes. He and Lara (Julie Christie) are both presented as willing to risk their lives to help others, regardless of class. This is how they end up working in a hospital on the Ukrainian Front, enthusiastic healers without any clear political allegiance.

The hospital itself is in a repurposed villa, the first example we see of a patrician home that has been confiscated for the greater good.

Yuri later returns to Moscow to find that the Gromeko home, which has “living room for 30 families,” has also been repurposed. He’s not particularly upset about it, acknowledging that it helps more people as a makeshift apartment building.

His wife, Tonya (Geraldine Chaplin), and his father-in-law (Ralph Richardson) are clearly less than thrilled to be living in just one large room (with a balcony). And like everyone else in Moscow, the family doesn’t have enough firewood. But Tonya, who was raised in luxury, is far too ashamed to explain that to Yuri. And so she empties the stove every time he leaves for work, hoping to fire it up again just before he returns. When Yuri comes home early one day and discovers Tonya’s embarrassment, he is so moved by her desperation that he steals firewood - an act which will trigger their flight from Moscow.

They head for their country house in Varyniko, after a remarkable train journey that really deserves its own column. After arriving, they discover that their manor house has also been confiscated, locked up and abandoned.

So the family settles into the cottage next door, the former home of their servants. It’s cozy and even Tonya’s father seems satisfied.

The issue of confiscation is a fundamental question within Doctor Zhivago. Sure, there are other critiques of the revolution, most of them represented by the violent excesses of Antipov/Strelnikov (Tom Courtenay). But the issue of private property is much more complex, particularly because of the differences between the characters. Tonya and her father might not know it, but their eventual exile is inevitable. Once the lush interiors of the upper crust have been redecorated by the art directors of Communism, they don’t fit anywhere.

Yuri and Lara are different. Both of them begin on something of a fringe between the aristocracy and the proletariat. But as the civil war drags on, the violence around them takes its toll. By the time they meet again in Yuriatin for the last time, in the dead of winter, they are entirely isolated. Yuri’s wife is in Paris, Lara’s mad husband in parts unknown. “This is a terrible time to be alive,” Lara says. And while Yuri disagrees, his poetic idealism isn’t especially convincing. In a civil war, there are few places to be comfortably “in between.”

The synthetic snow is beautiful and strange, and it has only taken on a stranger aspect in the years since. Even the little onion domes on the roof are covered in frozen snow.

They enter the main house, which has been empty since before the Revolution began. The interior is quite literally frozen, a palace outside of time. It is as if Yuri and Lara have escaped not only their immediate situation, but reality as a whole.

The house is full of the trappings of wealth, but rendered useless by the ice and snow. It’s the physical and metaphorical opposite of Strelnikov’s train, which violently propels the Revolution down the tracks to Vladivostok and back, a shrieking avatar of history itself. At otherworldly Varykino, Yuri and Lara no longer have to resist history, they can simply hide from it.

But it can’t last. Komarovsky crawls out of the past with an offer that Yuri can only half-refuse. Lara and Komarovsky ride off to an uncertain future, while he remains behind. Desperate for one last look, he rushes upstairs, only to find that he can’t see through the frozen window. And so he breaks through.

In a sense, this is a final answer to the central question of Doctor Zhivago: Can a life be independent of history? Yuri’s poetry isn’t considered subversive because it’s explicitly counter-revolutionary, but because it purports to have no politics at all. His life becomes complicated not because he sides with the Tsar or joins White Army, but because he supports no army. He lives for life and love alone, or tries to.

But revolution makes such a life impossible. The frozen Varykino is beautiful and haunting, but cannot truly exist. History can be survived, it can even be influenced, but it cannot be escaped.