Patricia Highsmith was born 100 years ago this week. The writer died when she was 74, leaving behind a collection of full of classics. Many of those novels were adapted to the big screen, her mellifluous psychological thrillers most of all. Strangers on a Train and the many stories of Tom Ripley being the most popular. It was through cinema that I discovered the author and ended up falling in love with her prose. I adore how she seduces and stabs, hypnotizing us with beautiful words, undercutting the splendor with her character's monstrousness.

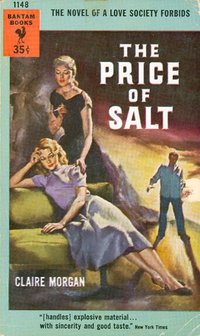

There was a mysterious softness to Highsmith's poisonous style, an insightful breath of romance that reached its apotheosis with The Price of Salt, later retitled Carol. First published in 1952, the novel was one of the first lesbian romances with a happy ending to see the light of day, making it a revolutionary text in many regards. By 2015, Todd Haynes and Phyllis Nagy finally told that story in celluloid, delivering what's arguably the best cinematic adaptation of a Highsmith novel…

Defining what a good adaptation is can be a tricky endeavor. There exist infinite possibilities of how to succeed in the business of transforming literature into cinema. Some find greatness through fidelity, while others use the book as a jumping start and never look back. Usually, I tend to prefer pictures that feel like they are in dialogue with their written brethren, argumentative siblings with complementing personalities instead of identical twins. If all the cineaste does is reproduce the words with no attention to how film and literature are completely different mediums, what's the point? One might as well just read the book and be done with it.

Defining what a good adaptation is can be a tricky endeavor. There exist infinite possibilities of how to succeed in the business of transforming literature into cinema. Some find greatness through fidelity, while others use the book as a jumping start and never look back. Usually, I tend to prefer pictures that feel like they are in dialogue with their written brethren, argumentative siblings with complementing personalities instead of identical twins. If all the cineaste does is reproduce the words with no attention to how film and literature are completely different mediums, what's the point? One might as well just read the book and be done with it.

Nonetheless, there's an argument for fidelity that I can embrace. To translate the experience of reading a book without being fastidiously literal about it can be wonderful. I often read Jane Austen books during the summers of my teenaged years and, every time I return to those novels, there's an air of summery delight dancing across the pages. Some films have captured that ephemerous quality that the novels have for me, and I love them because of that. It's the spell of memory and nostalgia, of sensual pleasure interlaced with the articulation of ideas. Those adaptations crystalize the feeling of a book more than they bother with the work's textual minutia.

In Carol, Nagy and Haynes have done a similar feat. They preserved the essential truth of Highsmith's effect on the reader, spinning her prose into tapestries of cinematic ravishment. In some regards, it's very faithful to the book, from the indulgent attention to cosmetic luxuries to Therese's illusory lack of knowledge about her wants. Still, there are notable changes from the novel, including the erasure of some of my favorite bits of characterization and period detail. Therese Belivet's vocation in the book isn't photography but theater set design, for instance. The descriptions of her frustrations as a young theatre professional were very dear to me. I felt oddly seen.

However, one can't mourn that script change since photography works much better in this different medium, informing the aesthetic idioms with which the film tells its story. The act of gazing at one's lover isn't expressed through narration but by the visual language of Carol, its cinematography attuned to Therese's eye as a photographer. It's through her eyes, we fall in love with Carol. The presence of the camera materializes that charged look. Cinema is, by default, much more material than literature and it's important to understand that what's vaporously ineffable on the page doesn't necessarily benefit from the same treatment on screen.

Therese is far from the only character reconfigured for her Silver Screen appearance. Despite its second title, The Price of Salt/Carol isn't really about Carol Aird. The book lives within the limits of Therese's subjectivity, her lover only existing to us through a smokescreen of infatuation, hurt feelings, and longing. She's more an idea than a person. This aspect is rejected by Nagy, her script fleshing out Highsmith's apparition of desire into a three-dimensional human being whose perspective is as relevant as her lover's. Notice that the screenplay is neatly structured so that our emotional entryway into the narrative's world subtly shifts from Therese to Carol as the narrative unfolds. That's only possible due to Nagy's transformations of the text.

Analyzing scripts isn't my forte, I admit, so it's with great shame that I find myself incapable of fully expressing the genius of Carol's adapted screenplay (that Oscar belonged to Nagy). At a loss for words, one finds guidance in superior wordsmiths. With that in mind, let's take a comparative look at my favorite moment from both the film and book of Patricia Highsmith's Carol and explore their dynamic as one tries to discover the key to their triumph. It's a small passage that occurs at the start of the sixth chapter when the titular character takes Therese to her home, subterfuges and unsaid words obfuscating the seduction being acted upon by both participants. Highsmith writes:

They roared into the Lincoln Tunnel. A wild, inexplicable excitement mounted in Therese as she stared through the windshield. She wished the tunnel might cave in and kill them both, that their bodies might be dragged out together.

I've long been enamored with this slash of mortal conjecture from Therese. Passion can be scary, the will to belong to another and have them in return often feels like a siren call for annihilation, an obliteration of the self in name of that which most call love. By allowing her protagonist's morbid musings to cut through the romance, Highsmith captures the verisimilitude of amorous abandonment that so many authors miss. It's vaguely nauseating, unappealing, and far from lovely, but it sings a song of caustic truth.

In her screenplay, this is how Nay approaches the same situation:

INT. CAROL'S CAR. APPROACHING LINCOLN TUNNEL. DAY.

CAROL and THERESE make their way cross town, as a cool winter sun combs through the car windows. CAROL appears at home" behind the wheel - relaxed, confident.

To THERESE, the world inside CAROL'S car is a revelation, from the tan leather upholstery and mahogany dashboard to the effortless style and elegance of its driver. The sounds of the world - even CAROL'S occasional chatter - have been replaced with the stillest MUSIC, the sound of air and light. The presence of this older, sophisticated woman, who wears silk stockings and expensive perfume, is intoxicating and unnerving in equal measure. Even Carol's purse, which rests beside THERESE on the seat, is quite unlike anything she has seen or examined so closely, full of mystery and make-up and fragrances. From there her eyes wander down to CAROL'S legs, clad in smoky silk stockings. Glancing down at her own legs, wrapped in sensible wool tights, THERESE wonders if she will ever be the kind of woman who owns such a car and wears such clothes.

The MUSIC broods slightly as THERESE looks straight ahead and the car enters the Lincoln Tunnel. The car plunges into the semi-darkness as if entering a cocoon, a delirious descent, which binds them together. She watches CAROL'S fingers grip the wheel, how CAROL squints slightly when she concentrates.

THERESE can barely suppress a tiny smile. But glancing back, CAROL suddenly appears to be miles away. CAROL switches on the car radio and Jo Stafford's "You Belong to Me" comes on.

THERESE leans back in her seat as they continue, speeding through the dark tunnel.

Highsmith is more economic with her words. After the excerpt presented above, she does interrupt the driving with dialogue between the two women but it's still a small text. Nagy, contrastingly, writes as if she's guiding the viewer's physical eye instead of the reader's imagination. She unravels the feelings Highsmith evokes and translates them into a language of images, composing a map by which the director and his team can find their path to the same ending point Highsmith arrived at. In the film, Nagy's words transform into a hurricane of sensorial information, Ed Lachman's camera seeming to explode the image in 16mm grain as the Lincoln tunnel is drowned in sublimated desire. Desire inflames the celluloid.

The music distorts itself as well, Carter Burwell allowing the score to include the light echoes of female voices. It's Therese's sudden wild reveries about wanting to live forever in that perfect moment, dying so that there's nothing after, encapsulated in a grammar that is cinematic instead of literary. Reading that passage in Highsmith's book, I feared its beauty would be reborn as clunky voice-over interruptions in Haynes' motion picture, but I should have been wiser than that. Neither the director nor Nagy disappointed. It may be presumptuous to say so, but Carol is the sort of cinematic adaptation that Patricia Highsmith should have been proud to have inspired. It's sheer perfection.

You might also be interested in reading Nathaniel's interview with Nagy at the time of Carol's awards push. You can find it here.

As for Carol, the film is currently streaming on Netflix.