Angels & Insects arrived in US theaters 25 years ago. The picture had had its premiere at the 48th Cannes Film Festival, where it competed for the Palme d'Or but it would take several more months for it to get a commercial release in the UK and the States. Once that happened, Phillip Haas' adaptation of an A.S. Byatt novel received plenty of acclaim from such renowned critics as Roger Ebert, conquering enough buzz to get a surprising, if deserved, Best Costume Design Oscar nomination. Nowadays, the flick isn't talked about, which is a terrible injustice as far as I'm concerned.

To rectify such lack of contemporary discussion, let's try to explore the sensuous perversions and entomological nightmares of this tale insects, incest, and insidiousness…

Despite being mainly set in the well-lit dining rooms and genteel parlors of Victorian England, Angels & Insects starts in the deep darkness of the wilderness. Over a black screen, strange noises move like a wave, drowning the spectator in sounds that feel somewhere between humanity and the insect world. As light breaks through the shadow, we find sweaty bodies dancing, leafy costumes clattering in a cacophony that reminds one of the cicadas' song. We're in the Amazons, in the company of a naturalist named William Adamson. He looks as if he were intoxicated by his surroundings, at home in the hubbub of the Native people even though he's a clear outsider. Cut to swirling ballgowns, blinding light, and blindingly bright colors, a society where nothing's as it seems.

After a tragic shipwreck, Adamson has found himself marooned in the polite world of the Alabaster clan, aristocratic patrons of the sciences that welcome him into their fold in the same fashion a predator might let their prey come close. We never see the transition from the jungle to the ballroom and arrive, like the protagonist, into this new environment with a degree of nervous disorientation. In seemingly no time, Adamson has become infatuated with the eldest daughter of the family, Eugenia. They soon wed after a courting made through clouds of butterflies and a proposal marred by the disquieting touch of giant moths. Before characters or audience can regain their bearing, there's pregnancy, and with it arrive the first signs of rot.

The central metaphor is fairly obvious and overbearing at times, the comparison between Victorian society and the invertebrate cosmos growing blunter by the minute. The Alabaster family rules itself like a hive of killer bees or some aggressive colony of warrior ants. The queen is the center of the world, her fecundity making her a baby-making machine, the womb-like sun around which every other member of the clan orbits. Hereditary insular wealth is a corroding agent that destroys the soul and the world which encircles it, helping set these rules of women as birthing agents and men as genetic continuators. Breeding and purity of blood are odious ideas common to the matters of animal farming and noble genealogy.

In Angels & Insects, all this concern with breeding means that sex is explicit but not sexy. As in the old tradition of arthouse European cinema, graphic licentiousness is often the vehicle for the most repellant depictions of human sexuality, naked bodies reduced to fleshy mounds writhing in ecstasy that looks more like agony than pleasure. The characters' scientific interests serve as a pretext for the filmmakers to regard them with the same clinical detachment of a taxonomist. Alienation is a purposeful feature of the formal and tonal idioms that define the film, even when it's depicting carnality. Its theses on the venomous perversion of the aristocracy aren't the most original, sure, but the way it presents its findings is shocking thanks to boldness of design, shamelessness, a willingness for prurient disgust.

Nonetheless, Haas' direction is virtuously elegant. His chilly formalism contrasts with the aforementioned taste for the vile, the vulgar, the sordidly voluptuous. So much so that even the innocent image of laughing girls in confections of pink ruffles, throwing rose petals at the camera, rings with a spike of unsettlement. Innocence looks obscene. After all this deliberate unsavoriness, the conclusions of the story feel perchance even more daring than the vivisection of aristocratic inbreeding. In the end, work and intellectual pursuit trump whatever follies the heart and the sex may encumber. It's the scientific research of Adamson and the Alabaster's steely governess, Matty, that prevails and sets the stage for future hope. The heart is fickle and so is the turgid genital, intellectual legacy is forever.

Regarding matters of performance, Mark Rylance is a wonderful lead, in the role of Adamson, weaponizing the quiet watchfulness laced with theatrical enunciation that characterizes so many of his screen performances. However, it's Kristin Scott Thomas' Matty that announces herself as the indisputable MVP of Angels & Insects. She cuts through the film's moral gangrene with the ease of a hot knife cutting butter. Dry and brittle, an angular counterpoint to the alabaster softness of Matty's employees, merciless with her tongue, she's uniquely willing to ravage the narrative's tone without mercy or concern. Watching her is a bracing spectacle, especially as the story reaches its end and the actress completely blows the flick open, her tortured sincerity festering into an incandescent rage.

If we return to the entomological metaphor, one can almost imagine Thomas' Matty as an intrepid black ant living among red predators, choosing to refuse her fate and the dominion of the bigger animal but always making sure she'll survive the feat. The thespian is wise enough not to play Matty as the clichéd archetype of the woman living in the wrong time. She performs the governess as someone so used to the social orders that she never outwardly bristles against them, preferring to make her path through the loopholes in the hierarchical contract of Victorian England. It's a perfect performance for which I'd have awarded Thomas with a Best Supporting Actress nomination in 1996, maybe even the win.

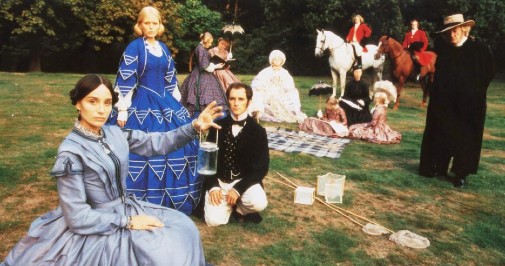

Speaking of awards, let's talk about those Oscar-nominated costumes. The designs serve to reinforce the insectoid horridness of the Alabasters, especially when it comes to the wardrobe's use of color. Aniline dyes had just become available at the time the story is set, popularizing the fashion for bold shades. However, even the most advanced dying technology of the 1860s couldn't hope to create such eye-searing textiles as the ones presented in Paul Brown's designs. Patsy Kensit's Eugenia spends the picture dressed in nightmares of 19th-century couture making her look like a variety of bugs, from bees to butterflies. Whatever entomological inspiration defines her outfits, one constant remains: she and the Alabasters as a whole are repellant creatures whose beauty is only appreciable if we stand at a distance.

Despite its title, there are no angels in this film, only human-shaped insects dressed in colorful carapaces made of silk and beautiful lies.