By Glenn Dunks

I’m not going to lie. There are times in Viktor Kosakovskiy’s buzzy new barnyard documentary, Gunda, that feel a bit like a colossal piss-take. Literally if you’re talking about that one extended scene of piglet urination. But between that, the one-legged chicken, the continued attention to the titular pig’s shaking udder, and its shiny black and white photography, the entire enterprise often feels like the punchline of an extended arthouse joke about what people perceive documentaries and international cinema to be.

I’m not going to lie. There are times in Viktor Kosakovskiy’s buzzy new barnyard documentary, Gunda, that feel a bit like a colossal piss-take. Literally if you’re talking about that one extended scene of piglet urination. But between that, the one-legged chicken, the continued attention to the titular pig’s shaking udder, and its shiny black and white photography, the entire enterprise often feels like the punchline of an extended arthouse joke about what people perceive documentaries and international cinema to be.

That isn’t to say it isn’t impressive. It is, frequently. Especially from a purely logistical standpoint as Kosakovskiy and Egil Håskjold Larsen’s camera fluidly encircles and follows its animal subjects with access that often defies belief...

But it’s also a proud festival title, the kind that one may slot into a schedule and find themselves drifting off to slumber throughout (guilty as charged) due to its hypnotic rhythms and calm, placid tone. It certainly isn’t a film I would expect many to actively go to a box office (virtual or otherwise) and slam down $20 for. “One for the black and white pig documentary, please.”

But I guess stranger things have happened.

It’s a slow film, one full of languorous tracking shots of chickens, cows and pigs—especially pigs, including Gunda the mother sow who gives birth in its opening sequence. But even at 93 minutes it’s probably slightly too long. Still, anybody who has seen any of Kosakovskiy’s earlier films shouldn’t be surprised that he didn’t give these animals anthropomorphised storylines with quaint British accents or even jaunty narration. This isn’t March of the Penguins and we should all be thankful for that.

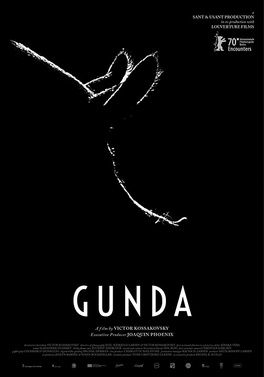

But when I tell you that famed vegan and animal rights activist Joaquin Phoenix is an executive producer should probably tell you that this isn’t all just cute piggies rolling around in the mud or, as in my favourite scene, drink rain droplets out of the sky as they peek out from their cubby. Unlike, say, My Octopus Teacher from earlier in the year, these animals’ purpose in man’s lifecycle is made abundantly clear and emphasised in its powerful final scenes (albeit not graphically, thank heavens).

In that sense it is a tough watch. Its grimness sneaks up on the viewer, disarming and in your face. I say this not to spoil the movie, but to correctly represent it to audiences who could easily be distracted by its elegantly filmed beauty. While sharing little in common beyond a pig at its core, it’s something akin to the difference between recommending Babe: Pig in the City on unsuspecting crowds who just swooned over Babe if you catch my drift. This isn’t another The Biggest Little Farm.

And what of Viktor Kosakovskiy. He’s a Russian director who’s quietly been making documentaries since the excellent The Belovs in 1992. That film, also set on a farm but instead about bickering siblings in post-soviet Russia, is a wonderful 60-minute excursion into a world at once foreign and relatable. He came to more international prominence thanks to his globe-trotting features ¡Vivan las Antipodas! and Aquarela, to which Gunda shares little in the way of scale. Gunda is a much different beast, the camera keenly focused on the animals as they exist on this farm, monitoring how they eat, sleep, birth, explore and, yes, urinate. The camera never even leaves ground level.

And that is sort of his thing. Whether it be melting glaciers or pigs in shit, he just let these stories unfold. And that is potentially why I’ve never fully been able to latch onto his later films as much as I want to. While we all know that the process of making a film is hard film, their relative simplicity can give the illusion of less critical insight into his subjects. Is this a personal film for him? I honestly can’t say.

He gives audiences a lot of credit in Gunda, definitely, where no voices or treacly score compositions interfere. The film is to be commended for that. Do I wish it had come down stronger on side of the other in regard to carnivorism (I am a meat eater, but I empathize)? Maybe. Or perhaps its truest strength that it can be read either way: by some it’s a work of art about the emotional impacts of our want for pork, while others see it as a celebration of sorts of the circle of life. By its end, however, I felt like I wanted something ever so slightly more from Gunda. Maybe that’s the complex of the movie: we never can know truly what is going on in their minds. Gunda is beautiful and wonderfully made, but while it certainly isn’t fast food, it hasn’t lingered quite as I would have expected from such an artistic undertaking.

Release: Played a qualifying release late last year before a wider 2021 release (at some point, I'm not sure when). Currently screening virtually as a part of MoMA's 'Contenders' series until January 10. Presumably they are waiting for potential Oscar attention.

Oscar chances: I would be... surprised. Pure nature documentaries have not been the doc branch's thing for a while now, and the few examples of that in (semi) recent times—March of the Penguins, Winged Migration—are very different beasts. But as I have been saying for years now, the branch has been getting adventurous. And while he's never been nominated, Kosakovskiy seems to have buzz and good will on his side as an important figure of the medium for whom this could be an opportune moment to nominate.