by Nick Taylor

Happy belated Thanksgiving, TFE readers! In the spirit of American History, here’s a nice slice of cinema on one of the US’s many exemplary passages of telling on itself: the Salem Witch Trials. Arthur Miller’s retelling of these events in The Crucible is so universally well known, but how much the 1996 film adaptation is part of that legacy? I first saw the film in my junior high English class (I’d already chewed through Miller’s play and Death of a Salesman before I was ever assigned them), and aside from a few indelible images of Joan Allen’s silent devastation at court or Daniel Day-Lewis’s artfully grimy self in prison, Nicholas Hytner’s rendition of The Crucible didn’t leave much of an impression. Where Shine presented an opportunity to check off a box I knew I wouldn’t check off without outside incentive, returning to The Crucible was a chance to find out once and for all how it holds up to the faded memories of a semi-interested high schooler.

Hytner’s adaptation opens by dramatizing the play’s unseen inciting incident, where one night a group of Salem’s daughters are caught dancing naked in the woods and are accused of performing witchcraft in the name of Satan...

Here, though, only one or two girls actually disrobe, which doesn’t really mitigate that they all threw herbs and plants into a boiling cauldron to cast love charms under the guidance of the Barbadoan slave Tituba (Charlayne Woodard). 17-year-old Abigail Williams (Winona Ryder), the ringleader of the girls, even kills a chicken and smeared its blood on her face to try and fatally curse a man’s wife! The sound design mixes their laughter to a monstrous pitch while the score amps up the drama and menace of the whole thing. The girls are caught in the act by Reverend Parris (Bruce Davison). Two of them, including Ruth Putnam (Ashley Peldon) fall into an unwakeable sleep, leading most of Salem’s townsfolk to fear witchcraft has taken hold of their fair town. Ruth’s mother Ann (Frances Conroy) is especially terrified, as her daughter is the only of her nine children to survive childbirth.

The Reverend Hale (Rob Campbell) is called into town to investigate, though John Proctor (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Giles Corey (Peter Vaughn) consider the whole thing a waste of time and believe the girls are simply acting out to avoid being punished. John’s suspicions also stem from his brief, passionate affair with Abigail which was discovered by his wife Elizabeth (Joan Allen). John tries to convince Abigail to quiet the town’s cries of witchcraft, but she refuses. Soon after, Abigail paints Tituba as Satan's servant to save herself, and Hale whips the slave until she names a handful of women Ann Putnam vocally blamed for her children’s deaths in order to save her own life. The whole flock of girls begins crying "witch" at those same women, and suddenly the entire town sees witches everywhere. The witch trials begin, and Judge Danforth (Paul Scofeld) is imported to oversee the cases.

That’s a lot of plot to negotiate, as well as a lot of key characters who drive it. One could understand any adaptation of the play that sees some parts of itself better than others, but The Crucible (1996) is wildly uneven in ways that threaten to topple it. If the film doesn’t actually begin with its worst scenes, it opens by foregrounding its least persuasive qualities. Hytner is garishly ungenerous in his depiction of the town’s girls, filming them as an indistinct pack rather than individualizing anyone who isn’t relevant to the overall plot (ie, Abigail and Mary Warren). The camera swoops and chases them every time they freak out and claim they’re being assaulted by the devil’s servants, getting caught in their fervor rather than saying anything about it. The heightened sound design is similarly constant whenever they scream in terror, and the score is all over the goddamn place. One could imagine a lot of nuance could be shown to a group of girls who end up becoming witch finders to save themselves from abject humiliation, but Hytner seems weirdly disinterested in most of them, reducing them to a simple mob.

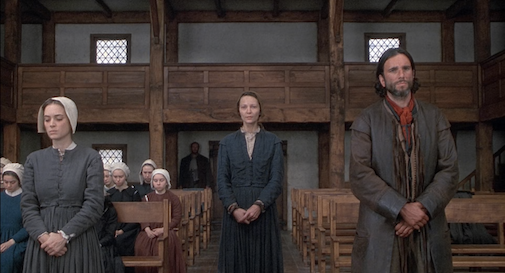

The depiction of the girls speaks to larger problems with characterization and filmmaking. You can’t say the production design or performances convincingly depict a 17th century vibe, instead reading like mostly-convincing filmed theater that could’ve used a bit more money or better cinematography to really pop. Even with these technical issues, though, The Crucible viscerally captures the frightening ouroboros of paranoia, fear, greed, pride, and decency that’s holding Salem in a death rattle. The makeup, too, is appropriately grimy for its Puritan era.

While the character complexity inherent in Miller’s script is still visible, only a few actors key into how their characters are trying to survive or profit off this new threat/opportunity including Charlayne Woodard in her small role. It’s offensive that the scene of Tituba’s beating and confession are primarily filmed and edited to showcase how the white characters reacting to her brutal treatment and the “information” she shares. Yet in this single sequence the actress shows us an angry, frightened personality under duress clocking what she has to do to survive and saying her piece before capitulating, without once suggested she really believes what she says about witches and the devil.

The cast doesn’t feel abandoned, exactly, but the work is uneven. Tertiary, heroic figures played by Vaughn and Mary Pat Gleason are better defined than the wormy antagonists embodied by Davison and Jeffrey Jones. Perhaps the character’s morality genuinely influenced how much Hytner was interested in shaping their performances. Paul Scofeld does authoritative, quietly complex work, showing Danforth as practicing a form of justice blithely unconcerned with its own contradictions, convinced of his mission, and possessing a bullish outrage at the possibility of being duped or losing face. He’s a hard man, but there’s an intelligence to his misguided determination, lacking the conniving bloodlust of Salem’s citizenry.

Wobbliest of all is Ryder’s interpretation of Abigail, which is dangerously undisciplined across the whole film. I don’t blame her for struggling with such a dizzying role, but Abigail is barely the same person from one scene to the next, sometimes coming across as a crafty, self-dramatizing manipulator and sometimes like a cult leader drinking her own Kool-Aid. It's rough as hell, and her own sense of moral and thematic weight on the whole project is completely scuttled.

The very best elements of this iteration of The Crucible are Daniel Day-Lewis and Joan Allen, who play the Proctors as normal, decent folks, equally colored by their spoken tribulations and buried complexities. My big high school theatre fear about John Proctor is that he’d be portrayed as a self-righteous ass flaunting his superiority until it bites him in the ass. Day-Lewis keeps John scaled to a real man, straight-backed and sensible but still weak to temptations to the flesh. His tenderness with Ryder in their first scene as he tries to let her down gently without mincing his intentions is so striking, as is his dueling sense of guilt and vexation at feeling guilty when in Elizabeth’s company. Allen refuses to pigeonhole Elizabeth as a pious martyr or embittered wife, conveying a woman whose betrayal has led her to look inward, trying to compensate for whatever deficiencies she imagines would have spurned John’s interest in another woman while balancing forgiveness, servility, and outrage. Both actors work nimbly with Miller's dialogue and the period-but-modern tone Hytner achieves. They prevent any one tone from overriding their work, organically earning their incredibly moving final scenes without conspicuously building towards a great reckoning. They shine the brightest lights on each other’s acting while standing tall in their own rights, and the conflicting senses of loyalty, love, and (self)-recrimination is the most powerful emotional through-line anywhere in the film.

It's not the greatest stage-to-screen adaptation, but the Proctors are so finely realised that any version of The Crucible would be proud to have them. I’m very curious to find a subtitled version of Raymond Rouleau’s 1957 French-language version written by Jean-Paul Sartre and starring Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, and Myléne Demongeot. Reviews at the time from critics and Miller himself indicate Sartre and Rouleau created a fierce, specific, divisive interpretation of the material. Hytner doesn’t marshall an exciting point of view about the play and his biggest stamps of authorship mostly misserve the piece.

Still, The Crucible's core themes of persecution and abuse of power are so potent that it's vital for any era, and Hytner gets two plantinum tier performance that'd elevate any take of this tale. It’s a solid adaptation and I’ll take it gladly.