by Lynn Lee

The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long. That isn’t Fred Hampton’s epitaph, but it could well be. Only in his case, it wasn’t even half – more like a quarter. At the age of 21, Hampton was already one of the brightest lights in the Black Panther Party when he was assassinated in his own home by the Chicago police, with help from the FBI, in 1969. The most tragic aspect of his premature demise wasn’t that he was just getting started; it was that he had accomplished so much in such a short time and gave every indication he could have done so much more had he lived. The second most tragic aspect was the identity of his betrayer: an African American FBI informant who had embedded himself in Hampton’s inner circle.

The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long. That isn’t Fred Hampton’s epitaph, but it could well be. Only in his case, it wasn’t even half – more like a quarter. At the age of 21, Hampton was already one of the brightest lights in the Black Panther Party when he was assassinated in his own home by the Chicago police, with help from the FBI, in 1969. The most tragic aspect of his premature demise wasn’t that he was just getting started; it was that he had accomplished so much in such a short time and gave every indication he could have done so much more had he lived. The second most tragic aspect was the identity of his betrayer: an African American FBI informant who had embedded himself in Hampton’s inner circle.

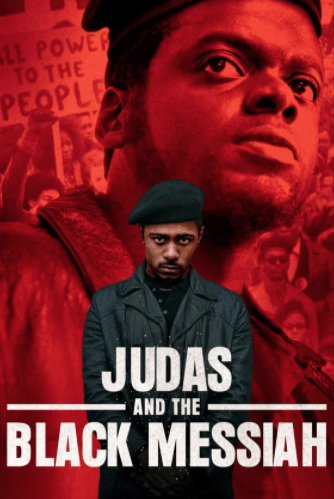

Both of these aspects get their due in Judas and the Black Messiah, the first non-documentary film to focus on Hampton and the man (and Man) who brought him down...

Directed and co-written by Shaka King and anchored by strong performances by Daniel Kaluuya as Hampton and Lakeith Stanfield as the informant Bill O’Neal, the movie delivers a gripping, politically timely, and thoughtful treatment of a particularly shameful chapter in U.S. history. Its portrayal of the Black Panther movement and Hampton’s role is admirably nuanced, if necessarily compressed, highlighting both their populist, cross-demographic appeal and the obstacles they faced from without as well as within. King also knows how to build suspense, even in a story with a predetermined ending (hell, one that’s practically written into the movie’s title), punctuating the mounting tension of O’Neal’s double agency with escalating, tautly shot standoffs between the Panthers and a law enforcement establishment determined to crush them.

So why, then, does the film also feel slightly remote and incomplete?

I think it comes down to the narrative focus on the Judas figure – an interesting choice, but ultimately a limiting one. That’s no knock on Stanfield, whose haunted eyes and jittery outbursts effectively convey O’Neal’s growing moral discomfort and fear of being caught. Still, as written, O’Neal remains an enigma. We see the external motivations for his actions: arrested for stealing a car and impersonating a federal officer, he’s quickly sized up by an up-and-coming FBI agent (a very good Jesse Plemons) as a malleable potential source, susceptible to both the carrot (money, sense of importance) and the stick (jail, having his cover blown). What we don’t see is what moves him internally, in that we never get a clear sense of whether he believes in anything other than his own survival. That may be true to the historical O’Neal, but it doesn’t make him an especially compelling central axis for the film. As others have noted, O’Neal, like Hampton, was painfully young – only 17 when he first began working for FBI, 19 or 20 at the time of the main events of the movie – a factor that’s somewhat lost in the casting of the pushing-30 Stanfield. (Kaluuya admittedly poses a similar age issue, though archival footage of Hampton shows a man who seemed older than his years, no doubt due to his preternatural charisma and self-possession.)

Judas is also fairly cursory in showing just how O’Neal was able to get so close to Hampton. There’s surprisingly little one-on-one interaction that suggests a special chemistry or connection between the two men. Perhaps for that reason, Hampton’s character development and most revealing moments, more often than not, don’t involve O’Neal at all. It’s reflective of the film’s oddly disjunctive nature that the two most interesting relationships in it – between Hampton and his girlfriend Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback), and between O’Neal and his FBI handler – don’t ever intersect. Fishback, by the way, may be the real revelation of Judas, projecting equal parts poise and vulnerability, tenderness and tough-mindedness as the poet, lover, and devoted supporter who nonetheless isn’t afraid to question and push back on Hampton’s revolutionary rhetoric.

As for Kaluuya, he doesn’t look much like Hampton but does a creditable job filling out the man behind the legend. He brings the oratorical thunder convincingly in the speech and rally scenes, which may be enough in themselves to get him a second Oscar nomination. His best moments, however, are the quietest ones: his courtship of and later heart-to-hearts with Deborah; a poignant conversation with the mother of a fellow Panther killed in a shootout with the police; and the last night of his life, in which his discussion with his comrades takes on a tone that’s far more contemplative than militant. It’s in those moments that we get the fullest measure of who Fred Hampton was – and what was lost with his death. B

Judas and the Black Messiah is now streaming on HBOMax and playing in theaters.