O FANTASMA (2000)

O FANTASMA (2000)

For the past few years, the Criterion Channel has highlighted taboo-breaking pictures in queer cinema with their series "Queersighted." For its fourth edition, programmer Michael Koresky invited film critic K. Austin Collins to select and discuss a series of works that look at film history through a decidedly queer lens. This year's installment features movies that go from 1930s Hollywood productions to 2000s Portuguese provocations. Controversial and wildly transgressive, these films run a gamut of genres and formalistic approaches, showcasing how it's possible to push the envelope both from within the Hays Code-abiding studio system and the vanguard of New German Cinema.

Before saying farewell to Pride Month 2021, join us in exploring ten films presented in this program...

SYLVIA SCARLETT (1935)

SYLVIA SCARLETT (1935)

The oldest movie in the "Queersighted" collection is an exciting addition exactly because it necessarily sidesteps the queering of narrative. George Cukor's 1935 Sylvia Scarlett was a flop upon release and, even though it's a beautiful historical artifact, one need not look too far to see why. Disjointed, sometimes erratic, and bound by a too-tidy conclusion, the picture's appeal is in how it illuminates a side of Katharine Hepburn's star persona neither Hollywood nor 1930s audiences were ready to embrace. Often dismissed as a handsome counterpoint to the era's glamorous screen sirens, the actress rarely got to explore or celebrate her androgyny. However, in Sylvia Scarlett, it's all on-screen, unavoidable, and magnificent, with cheekbones that could cut glass.

Forced to disguise herself as a boy, the titular character perpetuates the charade long after danger's over. Moreover, while in her male costume, she appears surprisingly natural and attracts both men and women, furthering the film's ambiguities of desire and self-identity. The best part is that this queer choice isn't especially underlined as a transgression within the movie, excused as a rational resolution to a complicated problem. Paradoxically, this casual nature only makes it more transgressive. In contrast, Basil Dearden's 1961 Victim – the first English-speaking film to feature the word "homosexual" – makes sure the audience is aware of every boundary that's tentatively pushed.

VICTIM (1961)

VICTIM (1961)

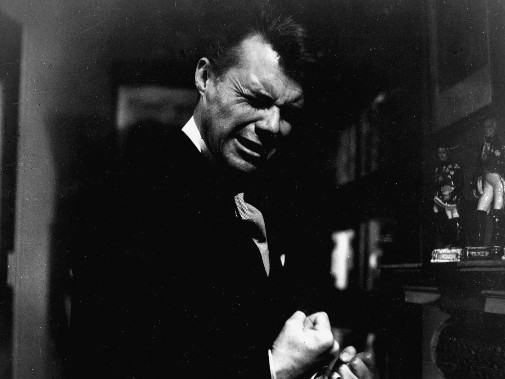

As in Sylvia Scarlett, the star's legacy and biography inform how we perceive the on-screen drama. In Hepburn's case, it was a matter of celebrity persona and long-rumored lesbianism. Dirk Bogarde is a thornier case study. Victim's leading man was closeted for most of his life, saving himself judicial prosecution in a country where same-sex attraction was still criminal if acted upon. Nonetheless, he never entered in a marriage of convenience, and some historians point to this as a factor in the British thespian's failed bid at Hollywood stardom. Watching Bogarde play a gay barrister dealing with a blackmailer and the threat of outing results in a palimpsest of queer anxiety, an agonizing spectacle that embodies the stifling claustrophobia of the closet perhaps a bit too well.

OLIVIA (1951)

OLIVIA (1951)

Compared to that Swinging Sixties hallmark, Jacqueline Audry's Olivia feels even more intoxicating. Despite being shot in 1951, the Sapphic costume drama is more libidinous than almost any mainstream movie of today. Adapted from a novel by bisexual author Dorothy Bussy, the action is set in a finishing school for girls in the latter half of the nineteenth century. As if a corseted sister to Guadagnino's Suspiria, Olivia portrays how the titular newcomer disrupts the power balance between a pair of older women, Edwige Feuillère's Mademoiselle Julie and Simone Simon's Mademoiselle Clara. Shot with elegant fluidity and intricate design, the school is a coven-like environment where lust flourishes in dangerous ways, blossoming into Venus flytraps that bite each other in loving cannibalism.

It's gorgeous and overwhelming, hypnotizing the audience with warm cologne-soaked pads until we're as lovestruck as Olivia. Detached from heteronormative morality, the film anonymizes men and pushes them to the margins, leaving the queer feminine perspective front and center. Even though tragedy befalls the school, there's no whiff of punitive justice, merely an acknowledgment of how Eros can be a guide to both ecstasy and sweet self-annihilation. It feels closest to Pier Paolo Pasolini's Teorema and João Pedro Rodrigues' O Fantasma within the "Queersighted" films. The Italian tale of otherworldly eroticism throwing a bourgeois cosmos out of balance is justly famous, and I've previously waxed rhapsodic about Rodrigues' cinema of kinky transcendence. Because of that, I shall not dwell on those horny gems, though I strongly recommend you check them out.

CRUISING (1980)

CRUISING (1980)

This time, I was more interested in those points where queer cinema and mainstream entertainment intersect. During the early 80s, two openly straight directors helmed American movies whose candid documentation of queer bodies feels radical nowadays, maybe even more than it did during their original releases. William Friedkin's Cruising and Robert Towne's Personal Best have been criticized, boycotted, and thoroughly cut to pieces by many a queer cinephile, academic, however. Cruising's the blue-lit Giallo-esque story of a "straight" detective going undercover into the gay BDSM subculture of New York to find a serial killer. The premise drips with sublimated homophobia, but the final movie's so weird it manages to kill these pernicious possibilities in their embryonic state.

Instead of the silver screen hate crime I anticipated, Cruising proved itself a warped psychological thriller whose twists paint a picture where the denial of desire -not its indulgence- metastasizes in murderous intent. It's flawed, and I won't invalidate how many can see it as dehumanizing. However, as a horror aficionado, the erotic crosshairs of fear, lust, sex, and carnage have always enticed me. There's also the treasured footage of a pre-AIDS lost world where leather-clad gay hedonism was finding its way into the multiplex. In 2021, when the presence of kink at Pride events became the cause for much debate, Cruising's blue-lit celluloid dream of wild sex felt more welcoming than shame-inducing.

PERSONAL BEST (1982)

PERSONAL BEST (1982)

As for Personal Best, its shots of bodies in exertion are so unrelenting that it's difficult not to feel the prickle of intrusive male gaze in a tale that's essentially about a young female athlete coming into her own. While still considering the negative critiques, I nevertheless fell into the movie's spell, its obsession with sportive bodies and a casual nudity one seldom finds in Hollywood products of any era. The imagery, its balletic slow-motion, and anatomical fixation feel connected to the central POV, organically extending from the characters. Moreover, there's little stress put on labels, closing fluid sexuality into boxes, or cataloging every impulse. This can come off as non-committal or evasive, but it's not out-of-step with what openly queer artists were doing in a less commercial context.

FREAK ORLANDO (1981)

FREAK ORLANDO (1981)

German director Ulrike Ottinger, for instance, hasn't been very open to the idea of her films being grouped into the category of queer cinema. Just glancing at her Freak Orlando is enough to confirm she's a one-of-a-kind creator. Enclosing the artist's hallucinatory oeuvre in a box that's simultaneously so vast as to be meaningless and small enough to smother does feel wrong. The anti-capitalistic sexually plastic verve of the work makes it thematically daunting, but the aesthetic is even more taboo-breaking. Folding historical periods into an amorphous blob that exists out of time, Ottinger evokes Medieval pageantry as well as a carnivalesque spectacle that puts the marginalized on gleeful parade. Her cinematic universe threads the needle between loving depiction and mockery, an uncategorizable unreality that stupefies the viewer.

For as deranged as Freak Orlando may appear, the structure follows a traditional, almost ancient, model, crossbred with Virginia Woolf and Tod Browning. For a more audacious, forward-looking exercise, we have the works of Marlon Riggs and Todd Haynes. Both of their filmographies have long been defined within the context of New Queer Cinema, their early pictures reaching for an indulgent referentiality that constructs the illusion of directly translating self-reflective thought into movie form. Riggs' Tongues Untied is like a punch to the solar plexus, so fractious and confronting, so devastating and divine. Instead of denying labels, it dissects and intersects them, sexual and racial. In a breathtaking scene, juxtaposed slurs become the matter from which Black queer cinematic perfection is created. In another, more joyful passage, finger snaps ring out a symphony of hidden meaning. Haynes' first feature, 1991's Poison, is less accomplished, though its Genet-inspired divagations set the stage for the director's miraculous future. Both pieces are essential viewing and fabulous for me to end this year's Pride Month.

TONGUES UNTIED (1989)

TONGUES UNTIED (1989)

You can watch this selection of 10 films as well as a conversation between Koresky and Collins on the Criterion Channel.