After a two-week hiatus, the Almost There series is back!

Blessed with an elastic face that can as easily twist into a clownish visage or a mask of tragedy, Jim Carrey is an actor prone to exaggeration. His maximalist tendencies don't always work, but they're sure to leave a lasting impression, whether playing up his funnyman routine or trying another register. While his legacy is built on comedies, awards bodies have responded better to Carrey when he's stretching himself as a dramatic performer. After his star rose with vertiginous speed in the mid-90s, the actor's first real foray into the Oscar race happened in 1998. It was then that, working with director Peter Weir, Carrey found the point where sitcom disintegrates into existential crisis, using his comedic skills to trace an odyssey of self-discovery. Despite AMPAS' marked disinterest, The Truman Show is one of Jim Carrey's greatest achievements…

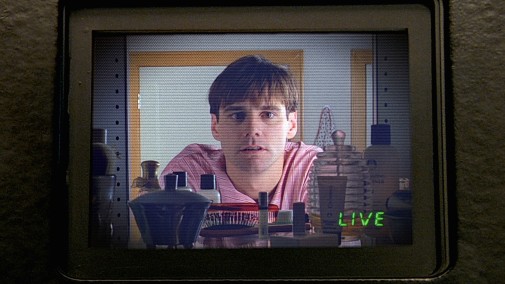

"There's nothing fake about Truman himself." Such words are spoken by the creator of The Truman Show, the TV hell inside Weir's satire against reality television, and the evils of corporations' control of human lives. Since birth, the titular protagonist has lived inside a massive studio set, an entire town populated by actors that perpetuate the illusion of normalcy. Nothing is true about the spectacle except for the human at the center. Introduced as he looks at himself in the bathroom mirror, Jim Carrey's Truman is just like his in-movie audience. He searches for escapism in the fantasy of another life, playacting a character of his imagination. That's what his multiple direct-address mirror monologues are about, an honest and naked need for something different from the ordinary.

It's a testament to Carrey's performative finesse that we're aware of how intimate these passages are and, consequently, how intrusive the camera's gaze is. The spastic artifice of Truman's social acting is absent altogether from these scenes, telegraphing the honesty of the man's daydreams. After all, this is a performance all about establishing different levels of selfhood – who Truman is to others and himself. All of us are composed of different masks, several selves that juxtapose and interchange, a miasma of personality segmented into facets, some of which are not for public consumption. Carrey's Truman has those facets too, but the prevailing vigilance of reality TV robs him of secrecy. Even the little things that are just for himself are unwitting pageantry for strangers' eyes. His life doesn't belong to him.

The dynamic exists in big gestures like how the mirror monologues end on a note of switching faces, as the man exits his private space and walks into the domestic stage. However, it also manifests in subtler nuances, like the modulated vocal variations of his office dialogues. When chit-chatting his way through conversations, Truman is in auto-pilot, but then a little surprise may startle him out of the routine. Carrey's façade crumbles for a millisecond, his eyes drift downward, and his quasi-singing delivery becomes a swallowed whisper. Just as it comes, it goes, but the actor's craft and Weir's voyeuristic visuals make sure we notice. Nevertheless, it's in the conversations with mother, wife, and best friend, as the lie starts to crumble, that Carrey showcases his most complicated tone management.

The full-on start of Truman's epiphany of derealization is an instance when the comedian's demonstrative physicality evokes a sort of balletic grace. Quiet paranoia crackling into a shattering of curiosity, it's a dance of anxiety transforming into euphoria. On the afterglow of the sequence, subsequent interactions become clouded by suspicion. One senses that, logically, this panic should feel claustrophobic, but watching Carrey letting lose is to taste liberation laced by hateful fury. Whatever complicity he might have felt for his wife has soured into distrust and, after a photobook discovery, his every scene with Laura Linney's electric ball of nerves and manipulations is tainted by rage. It's an ugly side of the character, borderline violent, something you'd expect a mainstream comedy star to sand down. Instead, Carrey does the exact opposite, leaning into the crispation choleric betrayal, sharpening the characterization's edges.

Later on, when talking to his best friend, Truman is aware and fooled by all the lies flying around - a paradoxical state. Carrey's teary-eyed nods, the repetitive reaction, almost seems to indicate that Truman wants to believe and, at that moment, is willing to fall for it. It's fascinating to note that this scene signals the transition of The Truman Show into a two-hander between Ed Harris's god-like eye in the sky and Carrey's unwilling TV star. Just as we arrive at a pinnacle of actorly vulnerability, Weir pushes against the audience's emotional engagement. A wall of alienation manifests, and biting cynicism undercuts Truman's melodrama. Such mechanisms could jeopardize the efficacy of the leading man's performance, but the contrary is true.

We're suddenly thrown outside the boundaries of Truman's inner-life as Carrey makes all of his subsequent quotidian performance into a self-aware act of fakery. It's startling, all the more unnerving because, during the first hour of The Truman Show, we've been trained to appreciate the specificities of the leading man's many levels of selfhood. Even before Truman evades the TV producer's schemes, the audience understands that something's wrong, that we're witnessing the prelude to an escape. His evasion is no surprise. When we finally find him again, Carrey has let go of mannerism and his Matryoshka performance within a performance, sublimating all of Truman's character into an unstoppable desire for freedom.

He's going to drown, but he doesn't even care. Death would be preferable to a life lived like this, imprisoned and forever observed. The dialogue points this out, but Carrey's performance confirms it. Hitting the outer walls of his prison, Carrey gives the words human weight. At that moment, he embodies an aching need for deliverance and the refusal of any other alternative. Finally, to top it all off, Carrey gets to play Man's confrontation with his Creator. What does he do then? The actor weaponizes his own quirkiness as a performer and makes Truman's last on-screen minute into an act of defiance. He spits the falsity of his life back unto the faces of those who devised it. When the movie's allegory threatens to topple itself into po-faced absurdity, Carrey makes it work. He adds an astringent note of barbed comedy, takes a bow, and leaves.

All that said, as much as one admires the performance, it's not a seamless monument of perfection. At this point in his life and career, Jim Carrey was not exceptionally skilled at reproducing the youthful innocence of a feckless teen. Apart from his evocations of lovesick longing, the flashbacks to Truman's early years find the actor indulging in an unnecessary mugging, confusion of social codes that don't quite fit the more nuanced version of the character as an adult. During cycles of dull routine, the adlibs don't always work either, sometimes tainting Truman's character with a mean streak that's less dramaturgically productive than his husbandly cruelty. Still, these are minor setbacks of an otherwise superb effort.

In the 1998/9 awards season, Jim Carrey got some traction in the race for the Best Actor Oscar. Amidst critics' honors and other such plaudits, his most significant get was a Golden Globe victory in the Drama category. Indeed, Carrey beat three of the eventual Oscar nominees. However, when nomination morning arrived, The Truman Show slightly underperformed, scoring only three nominations – Best Director, Supporting Actor, and Original Screenplay. Instead of Carrey, AMPAS picked Roberto Benigni in Life is Beautiful, Tom Hanks in Saving Private Ryan, Ian McKellen in Gods and Monsters, Nick Nolte in Affliction, and Edward Norton in American History X. The Italian actor would take home the trophy while Jim Carrey remains Oscarless to this day. Despite multiple opportunities, the Academy never embraced the actor, not when he had precursor love or even when they gave other awards to his movies.

The Truman Show is streaming on Fubo TV, AMC+, DirectTv, and Spectrum on Demand. You can also rent the movie on most platforms.