Last week, in the Almost There series, I took a look at Shirley MacLaine's Volpi Cup-winning turn in Madame Sousatzka. This week, it's on to another Venice Film Festival champion who got some Oscar buzz but failed to make it to the Academy's lineup. From a Best Actress winner to a Best Actor victor, from one elderly Oscar-winner to another, from The Apartment's leading lady to its leading man. In 1992, Jack Lemmon won two prizes at Venice, both for his performance in James Foley's screen adaptation of David Mamet's most famous play, Glengarry Glen Ross. The movie is iconic, full of memorable dialogue and oft-quoted one-liners, a treasure trove of vociferous acting, bursting at the seams with tired testosterone. Still, amid such a powerhouse cast of characters and acclaimed thespians, Lemmon shines brightest…

Like the play it's adapted from, Glengarry Glen Ross depicts two fateful days in a small real-estate office, where four salesmen compete for leads, capital, and their jobs. Constantly berates by mercenary-minded higher-ups, motivated through torrents of insults and corporate bullying, these salaried conmen have their livelihoods threatened. As it happens, only the top two sellers will have access to the best leads. The other two will be promptly fired. One must remember that these men's tactics are based on lies and deceit, games of shameless manipulation.

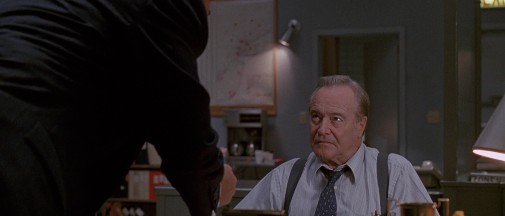

Moreover, not all of them are exceptionally successful at the grift, making the professional competition more akin to a circus of despair than a friendly race to the top. Introduced inside a stifling phone booth, making anxious calls to a daughter in the hospital, Shelley Levene was once prosperous. He used to make sales like nobody's business, earning himself the nickname "The Machine." However, things have changed, and we meet him on a slump, defeated by life, old age, failure after failure. Drowning in flop sweat and claustrophobia, Jack Lemmon makes us see Levene through a prism of manic verve, right from the first scene.

The Old Hollywood actor's theatricality and trademark lemony intensity percolate into a sinister sludge, an expression of anguish in place of his natural effervescence. As the character, he's pathetic, he knows it, and every overworked gesture of peppiness only underlines the defeated delusion. In Jack Lemmon's hands, Levene appears to be an erstwhile star rotted into a depressing, sad sack of brittle bones and old skin, the American Dream decayed, positively putrefied. If the phone scene didn't convince you, gaze at his reactions when faced with Alec Baldwin's abusive tirade cum motivational talk.

Seething with fury, the old star projects a percolated mass of resentment slightly tempered by the assumption that the corporate bully is right. For an actor with such overt physicality, so known for his elastic face, Lemmon can bring monumental meaning to such instances of frozen stillness. But, if anything, static silence coming from him only invites the audience to ponder what's going on behind those angry eyes. Instead of begging the viewer for attention, the Oscar-winning veteran draws his audience in, pulls them towards him. The mutinous swallowed down, rage is the hook. The rigidity acts as a fishing line dragging the catch from the water, the spectator from apathy.

If only Levene were as good at commanding people's attention. One wonders how this salesman ever fooled anyone. His shtick rings utterly false. The only honest thing about it is the stench of need that emanates from every word and clogged pore. It's funny that Lemmon didn't try to make the character into a wronged figure, preferring to genuinely making him bad at the job. On the other hand, the legitimacy of that job, that corpse of inhuman capitalism, is a separate matter altogether. Acting-wise, the scenes of failed sales see Lemmon offering a masterclass on the art of playing a loser, performing failure.

Every call, every visit, and conversation is turned into a maniacal spectacle, pretend secretaries interrupting regularly, and a mellifluous cadence takes over the speech, making it oily, greasy. Still, despite this grotesquerie, he also allows us to see the hurt of disappointment, the human cost of these systems of sales or bust, success or death. The glimmer of existential defeat that shines in the corner of his eye when a pitch falls flat is heartbreaking – more affecting for how muffled it is, barely seen amidst the tourbillon of showy business. Speaking of which, the cold night of morning arrives with ruinous robbery and some more acting with a capital A.

Indeed, a capital C, T, I, N, and G too, for that matter. That's especially true in Lemmon's case. After announcing a surprising sale, Levene explodes with pride, happiness. And yet, seeing him this ecstatic only brings up dread, like coagulated phlegm at the back of the throat. Look how the joy ferments into a bubbling puddle of undue cockiness, emanating sulfuric gases and toxic glee. He's a mad man laughing at the edge of a ravine, about to fall in and unaware of the imminent catastrophe. When he realizes that the braggadocio led him to slip up, it's too late – he's already free-falling into the dark.

As a final note, one should mention how superb Lemmon is whenever he shares the screen with Kevin Spacey's Williamson. The younger man sustains the interactions through a subtle rollercoaster of contempt, jumping into animal panic before settling on calculated boredom. The veteran flounders and tries to get on his feet. A half-sob escapes before another show of fake confidence can try to take center stage. It's a feeble feverish thing, a broken man being further shattered by his hubris, a tragedy that flourishes from that great mistake – when a liar believes their own lie and forgets what's true, forgets their fragility.

After taking the Volpi Cup and Golden Ciak at Venice, Jack Lemmon saw his internal competition steal his thunder. While the National Board of Review awarded him its Best Actor prize, other groups preferred to honor other performances from Glengarry Glen Ross. Both the HFPA and the Academy nominated Al Pacino as a Supporting Actor. In spite of his second-billing, Lemmon seemed better poised for the lead actor race, meaning he lost a place on the Oscar lineup to Robert Downey Jr. in Chaplin, Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, Al Pacino in Scent of a Woman, Stephen Rea in The Crying Game and Denzel Washington in Malcolm X. Pacino took home the little golden man, ending his decades-long overdue narrative with a disappointing victory. As for Jack Lemmon, he died nine years later with no additional Oscar nods. Nevertheless, two wins from a total of eight nominations is already an impressive record.

Glengarry Glen Ross is streaming on many platforms, including Showtime, Kanopy, and Hoopla. You can also rent it on various other sites.