The next episode of our series, 'Hit Me With Your Best Shot,' arrives Tuesday night. Since Alex Garland's Men is upon us, this week's selection falls on the director's breakthrough feature – the Oscar-winning Ex Machina. You still have time to participate! Here's Cláudio's entry:

Even though one tries to avoid the online discourse around Men – at least until everybody has had a chance to watch it – some grumblings are rather hard to block off. If that wasn't enough to affect the expectations going into the new movie, this look back at Ex Machina certainly does. The sci-fi chamber drama is a formidable reminder that Alex Garland is a better director than a writer, colligating blunt ideas and blunter dialogue with spellbinding form. Within the realm of glances refracted through glass labyrinths, insinuating architecture and eerie eroticism, Ex Machina triumphs. It's when its characters open their mouth to blabber on that the appearance of cinematic greatness gets spoiled.

Thankfully, Hit Me with Your Best Shot is about visuals, so we're in a safe place with Ex Machina. Whatever misgivings I might have, the film looks impeccable…

Truth be told, my issues with Ex Machina go back to 2015 and are not a recent development. I remember being mildly perplexed at its screenplay nomination, for, to me, that was the picture's Achilles' Heel. That's not to say I begrudge its unexpected success with the Academy. On the contrary, Ex Machina has plenty of award-worthy elements, spanning from its cast to the minutia of sound and set design. Indeed, Oscar Isaac is my choice for that season's Best Supporting Actor honors. Portraying the embodiment of a red flag as a tech bro with a God complex, he makes the picture's antagonist someone who's as magnetic as he is revolting.

His Nathan is a complex web of charisma and hubris, a mad scientist's cruelty crossed with the visionary's navel-gazing ambition. In Isaac's hands, Garland's obvious text feels more multidimensional than it is, trembling under the pressure of desire, palpable hungers that undercut platonic dynamics. Moreover, he plays to the camera like no one else in the cast, willfully shapeshifting his screen presence into a menacing prop or an object of oversexed fixation depending on what the scene requires. At a moment's notice, he might even switch up tonal registers and disrupt the movie with a blast of silliness: "I'm gonna tear up this fucking dance floor, dude. Check it out."

Beyond Isaac, Ex Machina's MVP is production designer Mark Digby who imagines Nathan's isolated abode as a modernist hallucination, somewhere between a bachelor pad and a human zoo. Domesticity and experimentation separated, the environment is made up of two levels. Above ground, the world's a minimalistic facsimile of a hunter's lodge, full of pre-cut logs and word-trotting knick-knacks. A stairway encased in glass separates the man-made structure from its surroundings, the divide between nature and artifice materialized as an umbilical cord that connects the complex's two levels. For those locked downstairs, that humble passageway is so much more than a staircase. It's a promise of liberty.

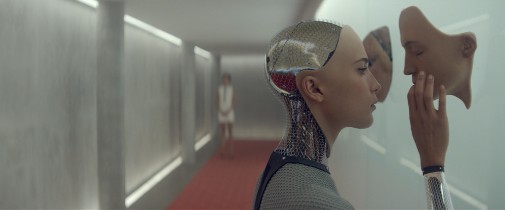

Most of what we see comprises repurposed sets and dressed locations, specifically the Juvet Landscape Hotel in Norway. And yet, Digby and cinematographer Rob Hardy make the beautiful environments look slightly off, suggesting a near future by way of alienation. Glass panels represent the medium by which most of these unrealities are offered. They encase Ava, the android, in a beautiful prison, invisible but for the building's seams and multiplying reflections. There's also the crack in one panel, a ghost of someone else's despair. Caleb, Nathan's naïve man-puppet, might think the mark was left there by Ava, but we'll find out soon enough that it's the work of another experiment. She's gone, only the shattered glass remains.

Digby and Hardy further frame these oppressive windowless spaces as an extension of Nathan's influence, from phallic punching bags to closets full of female bodies ready to be newly abused. Underground, in the confines of the man's private quarters, monitors and a wallpapered over with post-it notes give the impression of the scientist as a filmmaker. Like a director, he observes his actors at a distance, staging scenes according to his design. He is Frankenstein, Prospero, and Alex Garland himself all rolled into one. Logically, Nathan and how his influence is transmogrified in architectural lines were at the forefront of my mind when it came time to select a favorite shot.

However, something unexpected happened.

Revisiting the film seven years after my first viewing had a curious side-effect. Maybe because so many of its most prominent qualities and fragilities remained fresh in my mind, secondary details stood out. Notably, that was the case of Kyoko, the most backgrounded cast member whose very presence is defined by subservient anonymity. Played by Sonoya Mizuno, she's Nathan's mute servant who he treats abhorrently and uses for sexual release whenever he's feeling like it. As the drama's third act takes shape, Kyoko reveals herself as another of his experiments, Ava's silent sister and, eventually, her co-conspirator. Existing essentially as human scenery within the film, I was surprised by how much Kyoko haunted my reappreciation of Ex Machina.

Always listening, individual even when pictured as a non-entity, her treatment by the camera gets at the crux of Nathan's myopic imagination, the anxieties that pervade Ex Machina. As much as the lensing flattens her into an architectural fixture or accessory, details of behavior contradict this perceived reality. Kyoko's point within the dramaturgy is an instruction in understanding the personhood of what others define as an object, seeing when set ends and character begins. She's men's fear of women's autonomy taken to fetishistic extremes, a fantasy that fights back by complicating the libidinous gaze that looks upon her way before she goes rogue with a knife and murderous intent.

There's also the fact that she spends most of the movie in absolute silence, so there's no chance of marring the visual storytelling with lousy dialogue.

My favorite shot reveals Kyoko's contradictions with beautiful casualness. After being berated by Nathan, we see a glimpse of her sitting down in one of the complex's glossy corridors, her high heels tossed off to the side. Geometrically, it encapsulates humanity in disharmonious harmony with its environment, a shot of person-shaped disorder complementing the orderly lines of manufactured spaces. In retrospect, it's a shot of idiosyncrasy within the mad scientist's simplistic worldview. She's not as unaffected by abuse as her maker might think. Further still, she's not an unfeeling thing. If emotions are beyond her reach, she still projects unrest through the perfectly human gesture of sitting down to relieve aching feet from the punishment of heels.

Does she feel physical pain? Is Nathan that sadistic? Maybe, but what's important is that we feel her pain, translated through visual signifiers, framing, shot design, and gestural suggestion. That's cinema, baby.

Don't forget to post your #bestshot choices from Ex Machina so that Nathaniel can include them in tomorrow's Best Shot post. If you don't have time to screenshot the film yourself, check out Film-Grab and EVANERICHARDS.COM. Just make sure to credit your resources.