The Almost There series' month-long celebration of the Criterion Channel's May offerings draws to a close with a highlight from their Richard Linklater collection. In 2008, the Austin auteur made his most Oscar-ready project yet, complete with a dazzling supporting turn that seemed poised for a nomination. Me and Orson Welles is the well-researched and studiously put-together account of a teenager cast in the director's famous 1937 staging of Julius Caesar. The Academy usually loves these real-life tales, mainly when they include a good amount of celebrity mimicry, making the film an apparent shoo-in for Oscar glory.

And yet, Christian McKay's critically acclaimed take on young Orson Welles failed to secure a nomination. Considering precursor honors, he must have come close…

Perhaps Linklater's best choice in Me and Orson Welles was not wasting time before introducing its second titular character. Sure, he might be a supporting presence played by an unknown performer, but he's also the star. Not ten minutes have gone by before we find Zac Efron's feckless Richard James drifting past the Mercury Theater, attracted to the commotion outside. The teen with acting aspirations chats with some of the thespians outside, plays a drum roll, and, before you know it, Orson Welles is there offering him the role of Lucius in his politically-charged staging of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar.

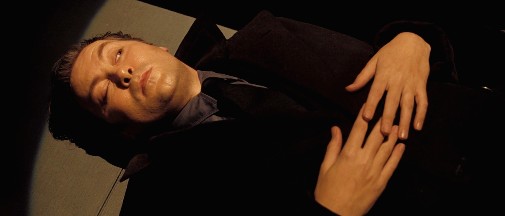

The instant he walks into the film, it's as if the camera were charged with a blast of energy, rushing to gaze upon the legendary Welles before he acquired that legendary status. Costumed to perfection and leaning on mimetic impersonation, McKay is a vision of showbiz history resurrected, pointedly artificial but not inappropriately so. Even in a first glimpse, we can denote how the actor's chosen to portray his character as someone bigger than life, a manifestation of self-regard so grand it can't help but manifest in a curated persona stinking of artifice. If there's anything overtly wrong with this picture, it's the actor's age.

At 35, McKay is more than a decade removed from Orson Welles' brattish 22 in 1937. The whole shock of a boy-genius depends on the dissociation between youth and achievement, something neither McKay nor Linklater can put across with their facsimile. The brashness is there, positively pulling the camera in over-excited push-ins, magnetizing everyone's attention whether they want it or not. However, the blush of tender age is heartedly missed, unbalancing the historical portraiture a great deal. But, of course, the film isn't objective in its purview of Welles, and neither is it told from his perspective. That's where the "Me" in Me and Orson Welles comes in.

For 17-year-old Richard James, maybe the director truly looked like a significantly older man, his authoritative creative genius adding a couple of years to his actual age. In that sense, McKay's casting reflects the illusions produced by brilliance, the intimidating aura of a self-centered visionary who's as concerned with projecting importance as he is with producing important work. He certainly bellows with enough force to squash anyone who'd dare to look down on him, anyone who might dare to look him in the eye. Everyone must regard Welles as a superior, a god above for whom all the rest are mere disciples.

Those words may suggest a one-dimensional caricature verging on inhumanity, some Wellesian cartoon shallower than anything the real deal ever created or did. Thankfully, McKay is too good an actor to fall into such traps. Linklater, for his part, has too much respect for a master of cinema and theater whose mythos is amply justified by actual greatness. Our first inkling of multidimensionality comes during the first rehearsal scene. Acting the part of an egocentric lothario, he walks in with his mistress on the arm and the theater manager pestering him from behind. Though he acts like a charismatic dictator, McKay lets through notes of mild disruption.

Amid the braggadocio spiel and dramatic ego, a shot or two indicate that Welles is aware of the manager's complaints. Moreover, the man knows they're justified though death will come before the great genius admits it aloud. Instead, he negotiates sensible compromises through scathing witticism, making himself look like the unshakeable leader. A tense look here, a nervous eye there, is enough to suggest this nearly unseen dimension of Welles – he's a most unprofessional-looking professional. Other anxieties about his wife catching his philandering ways represent another chink in the armor. These details don't weaken the characterization. They make it stronger.

Later, we get to see the talent behind the bravado. It's first evident in tiny increments of textual wisdom when openly discussing the Bard's play, finding ways to weaponize his cast's weaknesses and moods. However, the turning point happens when Orson takes young Richard with him to a live radio performance. The ride there reveals a softness to the star's menace, quickly followed by masterful flirting with a melodiously-named assistant. Greeting other actors, he's gracious, even charming, mellowing them before delivering a powerful performance complete with unexpected improv.

As the film goes on and opening night looms over, other facets of McKay's Welles show up, and those glimmers of light become cascades of luminous revelation. He always commands the room, whether irate over a sprinkler accident or charming his cast and crew with magic tricks. Furthermore, he earns people's respect, both on-screen and beyond it. That's true in instances of triumph and also in desperate times, imposing command over mutinous discontent or exploding at a set designer over matters of credit. He isn't always right, but he gets the job done, guiding the production to historic success.

None of this means Me and Orson Welles goes from parody into elegy in a straight line. On the contrary, McKay's characterization has an ugly side that's not encompassed by his tyrannical ways backstage. In regards to Richard and Claire Danes' Sonja Jones, the man can be cruel. Such facets aren't hidden or obfuscated. If anything, McKay makes them more evident by adjusting his snarling voice, adding a touch of calcination absent from his public blow-ups. He gets at the lacerating ways of actors so used to perform they can perfect their own venom, using professional technique to make realness all the more unforgiving, unforgivable.

Transcending the potential for flat clownishness, the performance is more complex than it looks on first impression, proving that mimicry can lead to genuine quality rather than meritless Oscar bait. It's a rare thing, but it happens from time to time. Here, the mimetic gamble becomes more tremendous when McKay is asked to act in a restaging of Welles' anti-fascist Caesar. Matryoshkas of performance within performance are always tricky, but this case comes laden with the weight of theatre history. During that miraculous reprieve where Orson can stop being himself, McKay doesn’t quite deliver a Brutus worthy of a lofty legacy. Still, he's solid.

Linklater may have brought Me and Orson Welles to TIFF 2008, but the film would only have its commercial release the following year. McKay nabbed nominations for the BAFTAs and Critics Choice Awards for that awards season, plus a vast array of regional nods and even some victories, either for Supporting Actor or breakthrough. However, AMPAS ignored him, choosing to nominate a McKay-less quintet. That year's Oscar nominees were Matt Damon in Invictus, Woody Harrelson in The Messenger, Christopher Plummer in The Last Station, Stanley Tucci in The Lovely Bones, and the victorious Christoph Waltz in Inglourious Basterds.

Beyond the Criterion Channel, you can find Me and Orson Welles streaming on Kanopy. The film's also available to rent on a variety of platforms.