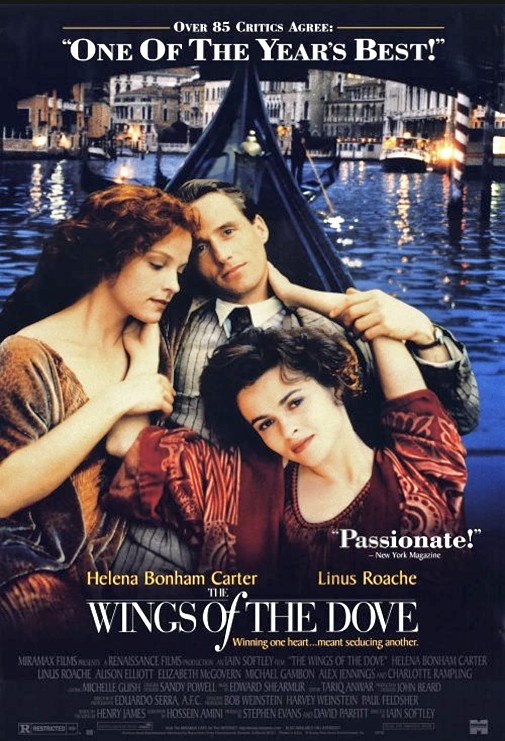

In 1997, Eduardo Serra became the first Portuguese person to be nominated for an Academy Award. This honor came thanks to his work in The Wings of the Dove, a Henry James adaptation directed by Iain Softley. This piece of trivia was one of the reasons I was so eager to watch the film as I first started to fall in love with movie awards. The other point of interest was Helena Bonham Carter, for whom I had a raging fandom in my early teens. After all, this was also the picture that had earned the actress her first nomination. It should have also won her the statuette. This was the first film I remember looking for with such avidness, going into international sites so I could order a DVD from abroad.

I fell in love with The Wings of the Dove when I was thirteen, and that passion has only strengthened in the years since. Indeed, every time I revisit it, I find new details worthy of admiration…

This time, for instance, I was struck by how sharp the editing can be, judicious and propulsive, while revealing the potential for poetry in Softley's frames. Nothing in the director's further filmography, or that of editor Tariq Anwar, has quite the same diamantine precision, making The Wings of the Dove shine all the brighter. It feels like a precious object, a rarity that manages to transcend the underestimations many might want to stick to it, wrong labels that equate costume dramas with stuffy mediocrity. There's nothing mediocre about this feature.

That's obvious from minute one when we meet our protagonist as she traverses through the London underground of the early 1910s. Kate Croy is the daughter of a formerly wealthy woman and a dissolute man of no means. Having recently lost her mother, she now finds herself living under the patronage of Aunt Maude. Coldly pragmatic and a bit mercenary, the older woman intends to find her penniless niece a good match, guaranteeing her a life far away from the destitute misery of the girl's father, who now wastes away in opium dens.

Money matters in this narrative, and no amount of romanticism can hide that truth. Love is a miracle, but it can't quell the hunger that comes hand-in-hand with poverty, nor does it provide other material comforts Kate has grown used to as she lives with Maude. However, heartlines of amorous devotion and sensual fixation still tether the young woman to that life she hopes to leave behind. As she walks from the train to the surface, through gates and lifts, that connection materializes beside her. He's Merton, a reform-minded journalist whom she kisses when nobody's looking.

Softley shoots this wordless introduction with devastating grace, slithering through the shadows of the London tube while the editing diffuses the distance between gestures. In three shots, cut like notes in a symphony's crescendo, we see how the lovers pretend to be unaware of the other's presence. Then, the eyes move, and bodies soon follow. Before we know it, their ascension is a passionate embrace, a dry orgasm of cinematic form articulating what could otherwise need lines upon lines of text to explain fully. They are bound to each other and inexorably pulled apart.

Sure, Maude has forbidden Kate from meeting her paramour, but there's more to it. Though it doesn't limit itself with bookish fidelity to the source material, the socio-economic specificities of James' prose ring through the film with a crystalline clarity. The kiss cuts directly to a dramatic close-up of Kate's eyes, staring straight at the camera, only to cut to a medium that reveals the preparations for a night out. The aunt paints her niece's face and adorns her neck with fine jewelry, putting her together like a doll. And yet, there's passive acquiescence in Kate's frozen form, her eyes caught in the mirror in what could be vanity if it didn't feel quite so introspective.

Helena Bonham Carter and Charlotte Rampling could say nothing as the two women, and we'd still get the gist of the situation, its prickly complexities. It's all in the images' construction, Sandy Powell's Poiret-inspired costumes with a hint of moneyed bohemia, and Serra's lighting of Carter's face to look like lifeless porcelain. It's in the actress' intelligent gaze, complicating the perfect "deer in headlights" countenance with a thorny calculation that glistens on screen. Kate is a tricky figure, a woman overcome by forbidden desire, a romantic heroine with a realist streak and enough brutality to turn the pursuit of love into something cruel.

The Wings of the Dove characters are fairly multidimensional and tricky to pin down, especially Kate. However, the story isn't as complicated. She initially rejects Merton until three months after the break, when an opportunity arises on the horizon. Kate befriends Milly, an orphaned heiress from the other side of the pond, now embarking on an extended trip through the Old World. Their friendship blossoms as the English woman sees the American as a way out of her economic trap. You see, Milly's infatuated with Merton. Moreover, she's dying.

And so, Kate schemes to bring her lover and new friend together, ensuring Merton knows the situation is temporary, a means to an end. The point is to secure Milly's fortune, wait for her premature demise and then marry as they've always wanted, love and wealth brought together in one fell swoop. As the American's European odyssey leaves London for Venice, Kate finagles her way to Italy as Milly's companion and also manages to bring Merton along. Her manipulations go according to plan, though there's no happy ending in store for this consummate liar.

I'm not sure I fully grasped the depths of Helena Bonham Carter's Kate Croy the first time I watched The Wings of the Dove. So much of her work is internal, a storm of contradictions, hypocrisies, and perilous ambivalences rolling at the bottom of the character's soul. It's a cerebral performance that's all about hiding and revealing, secrets sometimes shared with the camera, sometimes occluded to the extreme. There's great guilt mixed with jealousy, most memorably expressed in an epistolary monologue delivered into the mirror's surface. There's also twisted generosity, perhaps even a Sapphic shade to her friendship with Milly.

It's an incredible performance, surprisingly empathetic and brimming with silent compromises, the voracious observations of a preying animal. A slew of obstinate young women marks Carter's early work, demonstrative takes on inchoate spirits still finding themselves. Her Merchant ivory films are exemplary of this. But, then, her later career found the actress ossified into a stylized type, Goth melodrama for juvenile sensibilities alternated with self-conscious prestige. She still delivers remarkable feats on the regular, but never nothing as disciplined as her Kate Croy, the kind of work that becomes richer as the viewer ages and finds new facets to James' heroine.

Before re-watching Softley's film, I checked out Benoit Jacquot's modernized take on the same novel dating back to 1981. No matter how much screenwriter Hosseini Amini streamlined the novel for the '97 movie, he kept its spirit, themes, and ideas. Unfortunately, the same can't be said about Jacquot. Furthermore, Dominique Sanda is no Helena Bonham Carter. Her interpretation only made me appreciate how dazzling the British thespian is in the role. Even Isabelle Huppert as Milly - by far the French film's best asset - pales compared to Alison Elliott's SAG-nominated efforts. If Carter made Kate's ultimate generosity feel like a stab, Elliott made Milly's taste of punishment.

Linus Roache is appropriately beautiful as Merton, while a cadre of supporting actors sketch galaxies of meaning at the margins of the main action. Rampling was already mentioned, but Elizabeth McGovern and Alex Jennings deserve applause. But, of course, The Wings of the Dove's greatness goes way beyond its cast, cutting, and script. The picture's visual stylists evoke a sensual world, ripe to the point of rot, devastatingly gorgeous and erotic, while also feeling like a hand tightening its grip around the audience's throat.

Eduardo Serra's work is elegant without being showy, rendering London a labyrinth of treacherous shadows giving way to a crying atmosphere for the film's coda. Intimate spaces feel warm and cold simultaneously, while Venice is a dream of incandescent sensualities. The sets, by Andrew Sanders, materialize a point of transition in history, right before World War I and the Spanish Influenza shrouded the world in mass death. Powell's costumes delineate social hierarchies and power dynamics, they seduce the eye of the beholder while suggesting the tactility of Fortuni pleats against naked skin. Oh, what an intoxicating picture this is, growing richer and richer with each viewing.

The Wings of the Dove is streaming on Max Go. You can also find it on other platforms, available to rent.