The 76th edition of the Cannes Film Festival has begun in a flurry of controversy. Jeanne Du Barry, Johnny Depp's return to the silver screen after a much-publicized trial, was selected to open the festivities, prompting reporters to swarm the Croisette with polemic on their minds. The situation wasn't helped by incidents earlier this year, when director Maïwenn spat on a journalist, making their film about much more than just Louis XV's last mistress. In giving such attention to the kerfuffle, we've all played into Thierry Frémaux's hands. Regardless of the picture's quality, everybody's eyes are on Cannes, whether looking for a redemption story, an immoral scandal, or secret fashion messages on the red carpet.

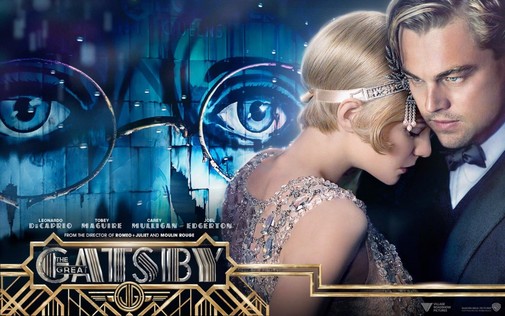

Then again, the Cannes opener is seldom an example of masterpiece cinema capable of accruing wide acclaim. More often than not, the titles blessed – or is it burdened? – with this honor tend to be mixed bags with big names attached, glossy stuff ready to act as attention magnets. Such was the case ten years ago when Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby opened the festivities to various degrees of critical hostility. Looking back, one is enticed by the possibility of reappraisal…

I don't know about you, but I love a paradox. That may be why I feel compelled to defend the CGI-heavy, frenzied to-a-fault Great Gatsby 2013. Everything that makes it lousy is also what makes it genius. Each adaptation flaw represents another reason why, to date, Luhrmann's vision is the best film yet made out of F. Scott Fitzgerald's era-defining work, the Great American Novel, through and through. Some would say the extravagance misses the point, tarnishing its literary origin through vacuous stylization, a lot of glitter surrounding a fundamental nothing. More naysayers would point to the modernizations littered around as a point against fidelity.

Although fidelity isn't always the point, Luhrmann and co-writer Craig Pearce feel fixated on Fitzgerald's words. It’s a tough thought exercise, but try to separate the glitz from the text when considering the movie. Framing device aside, you may find a slavishly faithful reconstruction of the book upon which the filmmakers have created their storm of audiovisual stimuli attuned to a post-MTV audience. But it's also distant from that origin in ways that transcend style, making assertions of fidelity somewhat dubious. As much as the screenplay keeps things in the same general form as the printed prose, as much as it tries to bring Fitzgerald's specific phrasings to the forefront, thematic intentions have been warped out of shape.

Examining the final film as a coroner might regard a corpse, we can pinpoint the stress marks across its body, the bruised ghost of Luhrmann's touch. In this autopsy, more of the killer than their victim becomes evident. At the very least, the director's Modus Operandi as a storyteller is plain to see, his romantic sincerity at odds with Fitzgerald's cynicism. As conceived by the mad Australian, The Great Gatsby is a tragic love story, no matter that the narrative doesn't support such conclusions or that the characters are incompatible with such earnestness. It's like the moviemaker took the obfuscations at face value, buying into the novel's illusions with such enthusiasm he becomes a metatextual twin to Gatsby. Or perchance a reflection of naïve Nick, smitten with his neighbor.

So, we have a screenplay adapted with plenty of fidelity that uses constant narration and graphic effects to bring the book to the screen. At the same time, it goes against the book's ruthless social observation, turning eyes away from its figures' horrifying hollowness. The movie does this to pursue an active misreading of its source. On the one hand, it pledges itself to a novel that came to define an era. On the other, every creative department does the most to spit on that era's specificities, transfiguration the past into a hyper-artificial phenomenon reflection of 2013 tastes.

Instead of classic jazz, the soundtrack is a Jay-Z-curated fantasia that could have rightfully filled the Oscars Best Original Song ballot all by itself. Instead of period reconstruction, the visuals are a festival of fakery, wardrobes gilded with modern Prada, and sets augmented with CGI. The very texture of the thing is sharp digital, rendered for a 3-D projection where depth works to make the world look like a pop-up book rather than an immersive universe. It's a bellow declaring war on the idea of authenticity. It's a formalistic denial of Gatsby's declaration that, of course, you can repeat the past – whether this is intentional on Luhrmann's part is beside the point.

It's beside the point to me, but I might be crazy. Who else but a crazy cinephile could look straight at this mess and call it brilliant?

Luhrmann feels antagonistic toward Fitzgerald's notions of emptiness, wanting to consider the characters as characters than as the vicious voids they are on the page. However, the cinematic construction many decry as a fault is perfect at capturing the bauble that shines prettily until you squeeze too hard, breaking to show nothing inside. Even the maximalist visual idioms that turn obvious symbolism into monuments repeat this dynamic, capturing something of the book other filmmakers have failed to reproduce. Bluntness in boldness is just right. The eyes of god are a pop of color in the digitally-drained landscape, the green light nothing but a computer-made facsimile of illumination, the doubled Toby Maguire's a metaphor of within and without literalized.

And the parties, oh, the parties. They are the kaleidoscopic carnival of the Jazz Age brought to life, anachronism and all. By focusing so much on the romance, Luhrmann bests many an essay on Fitzgerald's book, revealing the self-deluded mania, the sheer inhumanity, of these pre-Depression hedonists. Leonardo DiCaprio's failure as the lead to this love story is similarly so bad it's good, while Carey Mulligan's Daisy reads like a repudiation of sentimentality. He's a broken characterization. She's an airy idea with a voice full of money. They're never the beautiful paramours Luhrmann seems to be working for, never people. And yet, in this upside-down cinema, it makes sense.

In his inability to tell the truth, Baz Luhrmann succeeded in telling a story that's about untruths, those lies one tells others and themselves, the world, the times. The Great Gatsby does all that, combining incompatible ideas, paradoxes galore. And still, it also serves as Elizabeth Debicki's well-deserved big-screen breakthrough. What more can you wish for?

You can find The Great Gatsby on most major platforms, available to rent and purchase.