For Pride Month Team Experience is looking at queer & queer-adjacent moments in Oscar history.

by Nick Taylor

“I wish I had an abusive boyfriend who was willing to rob a bank to pay for my sex change operation.” sighed my friend Jude after we finished watching Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Pride is always an ideal excuse to make all my cool queer friends watch cool queer films (I do this all the time, mind you), and our Queering the Oscars series has created the perfect opportunity to revisit old favorites with good friends.

In the context of queer cinema, Dog Day Afternoon is a fantastic surprise to put in front of a crowd, since it doesn’t announce itself as such from the outset...

It also doesn’t completely reorient itself from its ongoing themes and concerns once we learn it’s 'family'. We’re hooting and hollering in support of this weirdly threatening-yet-gentle “Attica” shouting fuck-up...only to learn he’s queer, too? Fuck yeah! Even better.

Leon Shermer (Chris Sarandon, in his big screen debut), the frazzled wife of our narrativizing, unstable, fundamentally decent bank robber Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino, sweaty dreamboat extreme), is not who we were expecting to see pop out of a police car. You see the mother of Sonny’s kids frantically talking to the cops while nervously handling her toddlers because she has no earthly idea what to do with herself upon learning her husband is holding hostages with his best bud. You’re ready to see her when they announce Sonny’s wife has arrived. But no! Instead, Leon pulls herself out of the backseat wearing a weathered bathrobe, static-frizz bedhead, and a five o’clock shadow, and Sonny smiles the biggest, toothiest grin he’ll ever wear in the whole film. “Happy birthday, Leon!” he shouts to his wife, and she faints dead on the spot.

It’s a shock, arguably more shocking than the many unpredictable swerves fate has already handed this spectacularly failed heist, but Leon is not treated as an excuse for outlandish spectacle, or as resolutely “other” compared to the dozens of indelible figures who populate this film. Her truth and her desires are as significant as anyone else’s. The sensitivity and humanity endowed to Leon is as much a tribute to Sarandon’s Oscar-nominated performance as to Sidney Lumet’s direction and Frank Pierson’s script. That sensitivity is tangled up in what’s problematic and progressive in his casting and the role itself, by today’s standards and those of the 1970’s. Allow me some preamble before saying a word about Sarandon’s actual acting, but I promise we’ll get there.

So, context: The real life bank robber, John Wojtowicz, was quoted as saying to the police: “I want them to deliver my wife from Kings County hospital. It’s a guy. I’m gay.” about his wife Elizabeth Eden. Using male pronouns for Elizabeth pre-transition was seemingly fair game, though I will be referring to Leon with she/her pronouns in this article. When casting the role of Leon, Lumet only sought out cis men. Elizabeth Coffey, a member of John Waters’ repertoire who’s likely best known as the nonplussed young woman who out-flashes Raymond Marbles in Pink Flamingos, auditioned to play Leon, but Lumet said she was too beautiful and feminine to be convincing. He referred to photographs of Eden taken at the scene of the robbery for Leon’s makeup and outfit, though it’s not evident where the fuck the 5-o’clock shadow came from. One might point out that Sarandon doesn’t look much like Eden, who was quite feminine and beautiful in a way Leon isn’t. Dramatic license abounds across other aspects of Dog Day Afternoon, like John Cazale being roughly 20 years older than the real Sal Naturile, but it’s worth pushing against Lumet’s choice to embrace a masculine presentation of Leon.

Between all these different sensibilities around casting, representation, etc etc, what about Sarandon’s actual performance? What of his acting, if we can accept it to be separable from these other elements?

I don’t think it’s unfair or ungenerous to cede some problematic aspects to the standards of the times. Referring to Leon by male pronouns does not strike me as disrespectful, even if I won’t do it. Casting cis men as trans women and sanding down their femininity aren’t exactly archaic practices, though whether that makes it okay here is up to you. Maybe we can draw a pipeline to Dog Day Afternoon and unsavory, Oscar-baity, less layered depictions of trans people, but by its own standards and those of today, Sarandon and Dog Day Afternoon largely come out ahead for me.

In short, I think Chris Sarandon’s work is very, very good, if not so exemplary that I wouldn’t trade his Oscar nomination (the lone citation for the supporting cast) for putting John Cazale or Penelope Allen in the spotlight instead. The peach fuzz isn’t his fault. Eternally holding one hand at his throat to hold up his bathrobe like a life preserver is a legible, actorly choice. But would a fuller physical vocabulary have fleshed out Leon’s character further and productively cut against some of the neuroticism and frailty written into the role? Even so, there’s dimension and messiness to Leon’s desires and her relationship with Sonny, and Sarandon plays all of it with the same sincerity, intensity, and insight as the rest of Lumet’s inimitable cast.

There’s a light, exasperated humor to Sarandon’s line readings, likely borne from Lumet’s direction that he play the role as “Less Blanche DuBois, more Queens housewife”. The comedy in his performance doesn’t strike the same tenor as the incredulous pile-on of fuck-ups in the opening 30 minutes when Sonny and Sal rob the bank. You could call the tone of his performance sitcommy, for better or worse (especially the accent), but Sarandon credibly dramatizes this direction into Leon’s demeanor instead of using comedy as a device to stand outside his own character. The edge to these comedic instincts - often baffled, sometimes despondent, occasionally happy when the moment is right - suggests someone who’s so worn down by her life she has to choose between chuckling in amusement or breaking down again. There’s the faintest hint of a laugh line when Leon utters “He’s been trying to kill me since June”, yet Sarandon’s face couldn’t look more serious.

Leon states this line sitting in the barbershop across the street from the bank, which the local police and the feds have taken up as a base of operations. Her conversation partner and the man in charge of the cops is Captain Moretti (Charles Durning, reliably textured as ever), who engages Leon’s testimony with real gravity. This is as much due to Sarandon and Durning’s acting as the sensitivity of Lumet’s camera and Pierson’s writing, but I really appreciate how these characters treat each other without mockery or suspicion. There’s no time wasted trading barbs or bigotries. We’re not gonna shout “Solidarity!” at a cop who's still threatening to arrest her as an accessory to make her cooperate. But it's one of many, many unexpected interactions in Dog Day Afternoon that really elevate it.

I also have no caveats for how Sarandon plays the ten minute, semi-improvised phone call between Leon and Sonny. The rhythm of their dialogue, the shifting between unendurably heavy topics and barely-there jokes, the way the two keep falling back on longstanding arguments throughout their relationship in the middle of plainly discussing the current pile of shit they’re stuck in - all of it speaks to the intense, downright domestic bond Leon and Sonny have forged together. For all the pain they have caused each other, they care tremendously, and it’s the sort of unfakeable, bone-deep dynamic any two performers should be proud to capture. Ten minutes of conversation, and Leon and Sonny come into clearer focus as individuals and as a depiction of one partner’s thorny, messy, utterly profound devotion to their transgender spouse than the endless sludge that, say, The Danish Girl achieves in two hours.

I love how the camera follows Sarandon as he sits and swoops through the barbershop, zooming and panning and only later deciding to stay completely still while cutting back to Pacino’s frozen posture in front of his frozen camera. The scene starts with Leon’s face barely visible in the frame before she shoots upright in indignation to tell Sonny off for martyring himself when he’s really putting everyone except himself in harm’s way. She knows more than anyone what kind of shit Sonny can pull, and still the tragic momentum of the film can’t prepare us for how right she is. More than that, in a film that’s so magnificently gotten us on Sonny’s side, it’s almost as galvanizing to see his wife tell him how full of shit he is, if only for a moment.

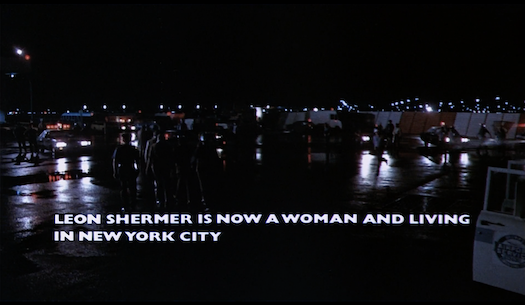

So, as I said earlier, Sarandon gives a very good performance. Should he have won the award? I can't compare him to the actual winner, as I'm not going to spend Pride month watching The Sunshine Boys, but he'd be a worthy winner. Given that I’ve spent less time on the distinct qualities of writing and direction buoying a great performance in past write-ups on acting, I have to admit my reactions to Leon probably have as much to do with Lumet and Pierson as to the specific contributions Sarandon is making as an interpreter, if not more so. Fair enough, when the writing and directing are both this good. Sarandon fulfilling the challenges provided is no easy feat, let alone enriching them. Sure he’s not as great as John Cazale, but who is? Leon is a truly indelible character, the fulcrum of one of the best American independent films in an era full of truly groundbreaking masterpieces. She’s as much a landmark now as she was then, and even if I have notes for him and Lumet, Sarandon is so crucial to this alchemy that I’m totally besotted with his performance. The phone call alone is worth its weight in cinematic gold. And when the closing credits tell us Leon has gotten her gender affirmation surgery and is living as a woman, I couldn’t stop smiling for her.