For Pride Month, Team Experience is looking at LGBTQ+ related Oscar nominations...

by Nick Taylor

Hello! Are you an enterprising young queer and/or MILF lover fresh off the newest season of Yellowjackets looking for another story of dangerous, imaginative, mentally unwell young women starring THE Melanie Lynskey? Would you like it to focus on an obsessive life-bond so intense it has almost no choice but to be queer? What if this one was based on a true story? Then have I got a film for you! Try your hand at Heavenly Creatures, the restaging of the infamous Parker-Hulme murder case in 1954 New Zealand about two pubescent girls so wrapped up in the fantasy world they’ve created over two years of isolating friendship that the only way the can imagine protecting each other from life’s unsustainable realities is to kill Mom.

Heavenly Creatures was directed by Peter Jackson, an inspired, imaginative artist whose soul would soon be held hostage by The Shire for decades. The film brought Jackson to international attention for the first time in his career, and netted an Original Screenplay nomination at the 1994 Oscars for himself and his writing/life partner Fran Walsh to boot. This is the sort of Screenplay nomination I deeply admire the Academy for making, even if I wish this pocket of support could have somehow translated to love for the direction, the actresses, the cinematography, and every technical element necessary to bringing Borovnia to life...

But before one builds a body suit of a man-sized clay sculpture of Orson Welles, one must first write it into the script. Walsh initially pitched the idea of dramatizing the Parker-Hulme case to Jackson, who up til that point had made horror-comedies noted for their satirical POVs and silly, intense gore. Jackson, Walsh, and producer Jim Booth, a longtime collaborator of Jackson’s who died after filming was completed, agreed to center the film as a story of friendship gone horribly awry. Walsh and Jackson read newspaper coverage of the murder trial, which recounted Pauline and Juliet’s relationship and their crime as a salacious act of unbridled devilry. Walsh and Jackson rejected the idea of portraying them as evil incarnate. To better understand their subjects, they conducted a nationwide search to interview as many people who knew Parker and Hulme as possible, and used Parker’s diaries as a chief point of reference for who these girls were and how they understood the world. To them, the two registered as intelligent, lively, outcasted girls, prone to mordant streaks in their humor and outlandish creative impulses.

This kind of incredibly thorough research, combined with a sense of purpose and sensitivity towards subjects who might not invite such treatment, and without sanding off their nastiness or “solving” their motive, is already a creative, tantalizing foundation to premise this script. It’s not an automatic guarantee of success, but Jackson and Walsh knew the movie they wanted to make and the movie they didn’t. I’m glad we don’t have the courtroom drama version of this tale, or one that made the girl’s bond into a cruder, flattened object, simultaneously open to fetishism and derision.

Instead, Heavenly Creatures presents the relationship of Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme (respectively embodied to breakout fame by Melanie Lynskey and Kate Winslet) as something utterly all-consuming, impossible to reduce to any one interpersonal dynamic, point of interest, or emotional response on the part of the audience. The way Pauline and Juliet come alive in each other’s presence is so real and so lovely, yet their romanticism only underlines whatever real-world intrusion is motivating the girl’s descent inward to Borovnia. Their individual personalities are sharply defined in Lynskey’s glowering, watchful reserve and Winslet’s self-theatrical extroversions, in the different ways they seem supported and suffocated by the lifestyles afforded to them through their class status. These strands aren’t spelled out, but they’re presented so that the audience grasps the impact of these differences and commonalities.

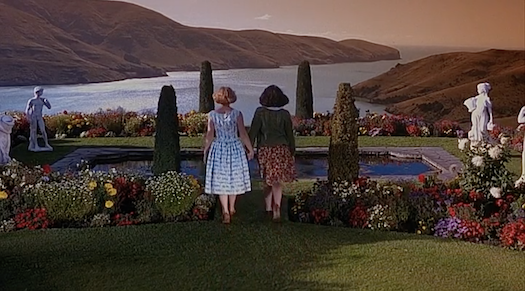

On the other side of reality, Borovnia always functions as an idyllic dream world, a playground to experiment with subconscious desires, and a transparent respite from so much else going wrong in their lives. It’s not the most radical insight into how a pubescent girl might use a fantastical made-up dynasty, but it’s more generous than a different writing team might have conceived, and it allows for simultaneous readings of the same event rather than blunt cause-and-effect machinations on something as complicated as desire. More than that, Borovnia is never inconspicuous. The blurring of fantasy and reality comes primarily from cinematography and sound work, and the transportations between settings are so defined that we cannot write off the girls as “just” losing themselves in a fantasy land.

The nameless friend I watched this with had some qualms about Heavenly Creatures’ overall structure, that there’s connective scenes missing throughout the film. He mainly pointed at the build-up of Pauline and Juliet’s friendship in the early going, and no deeper explanation of the decision-making from the parents and their children in the lead-up to the many separations going on in the last half hour. I don’t disagree that these scenes are absent, and I do wonder what a slightly longer film would add to the proceedings - not even grafting new scenes onto the existing skeleton, but expanding some of the ones we already have. Even so, this critique points to an absence in dialogue which is still present in the imagery and ideas derived from the text. Perhaps because Jackson and Walsh wrote the script knowing he would direct, they trusted in his ability to productively dramatize these gaps, foregoing words when a kaleidoscope of blunt-force, complicated visual schemas could reveal just as much.

The dexterity of Alun Bollinger’s cinematography - juxtaposing Hollywood melodrama with post-Raimi horror grammars and ‘90s maximalism - in tandem with the ferocity of its editing and sound design, productively serves Jackson and Walsh’s tendency of quickly establishing new norms only to immediately flesh them out and transform them. Pauline and Juliet’s friendship does happen very suddenly, going from forced partners for an art class to recognizing a shared history of illness, creativity, and Mario Lanza love in very little time. They’re strangers, they see something in each other, and then they’re the best of friends, and it takes about as much time to happen in the film as it did for you to read this sentence. Their romance, if we’re to call it that, springs organically from the different personas they attach to themselves in their fantasy lives, but as with Dog Day Afternoon’s own restaging of a well-publicized crime, queerness is irrefutably central to the events unfolding without quite being the main driver.

After Heavenly Creatures was released, Juliet Hulme made a statement to the press that although she and Pauline were deeply obsessed with each other, she did not consider herself or their relationship homosexual in nature. Parker has never spoken to the press, so who knows what she thought of it. Far be it from me to contradict Hulme’s recollections. I will simply say I’m grateful Heavenly Creatures is able to sexualize Pauline and Juliet’s relationship without using queerness as the epochal sin behind what’s wrong with them. There’s just too much going on. The fact that they choose to re-enact how each member of their royal court would ravish each other in bed in the final quarter of the film probably isn’t even in the top five most outlandish things they do.

This feels like the subtext of Pauline’s strong-armed visit to a psychologist - this girl just fantasized about her clay heir butchering you, you list all these troubling things about her recent attitude, and the gay stuff is the problem? My unnamed friend saw this whole scene as very ‘90s in execution, and he’s right, though again, I’m so glad Jackson and Walsh let the girl’s sexuality be one of many dynamics informing their bond, conspicuous and inalienable without being the key to "unlocking" them.

To divert from the leads at the end, it’s a boon to Heavenly Creatures that Jackson and Walsh give as much dimension to Juliet and Pauline’s parents as they do. They’re not one-dimensional monsters, and though there’s some fairy-tale archetyping imbued through Paul’s subjective filter on parts of the story, they’re never reducible to the paragons their daughters imagine them to be. Mr. and Mrs. Hulme’s parenting styles are symptomatic of how much control and fulfillment they feel in their own lives - him proprietary of his patrician status but not quite committed to his child, her indulgent of freedoms seemingly less catastrophic than the ones she’s allowing herself. Their affections and concerns are real, tangled as they are in their own drama, and they’re slightly too pathetic by the end to be flat villains. Mr. Rieper (Parker’s family name was Rieper until it was uncovered that her parents never married during the murder trial) emanates such affable, working-class paternalism.

Lastly, poor Mrs. Rieper emerges as the most textured of the adults orbiting these girls, alternating hard and soft tones always informed by real care. Honora Rieper is one of the most tragic mothers in cinema history (a very competitive field for sure), and it’s all the more heartbreaking because Jackson and Walsh have made her relationship with Pauline so fraught while rooting her mother’s actions in bone-deep understandings of matriarchal duty. That her story takes such strong claims on the audience without hideous foreshadowing is yet another triumph of Heavenly Creatures’ ability to juggle so many elements and ideas. Before writing this piece, I didn’t give Jackson and Walsh’s script enough credit for enabling the marvelous visuals and performances. It might not still be the first thing I think about in future considerations of the film, but it’s so gutsy and ambitious, and it would have been as deserving a victor of 1994’s Original Screenplay prize as the film that actually won.

More 'Queering the Oscars'