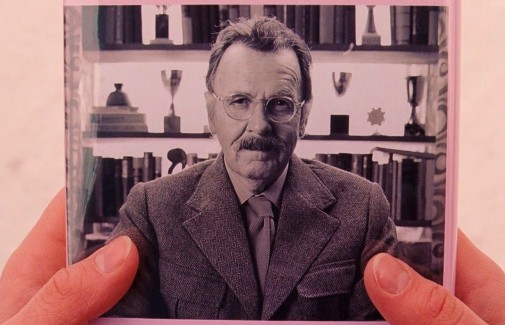

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL (2014) Wes Anderson

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL (2014) Wes Anderson

True character actors often feel like a thing of the past, one of those artifacts of bygone eras lost in our collective trudge forward. And yet, some performers keep the idea alive into the 21st century, shining brightly as something other than an all-consuming star. Such was the case of Tom Wilkinson, the two-time Academy Award-nominated actor who died suddenly last Saturday, surrounded by family. He was 75 years old.

I concede that it might feel wrong to start the new year with an obituary. Still, one must pay respect to the fallen titan, an artist of integrity and craft whose filmography contains over a hundred credits, from minor indies to awards juggernauts, chamber dramas, blockbusters, animation, and the whole shebang. On this sad occasion, let's remember the greatness of Tom Wilkinson…

THE SHADOW-LINE (1976) Andrzej Wajda

THE SHADOW-LINE (1976) Andrzej Wajda

Born Thomas Geoffrey Wilkinson on February 5th, 1948, the future thespian was the son of Leeds farmers in Yorkshire. His youth wasn't entirely set in god's own country, however, for the Wilkinsons moved to Canada for half a decade before returning to the UK, resettling in Cornwall. Perhaps these travels inspired Tom Wilkinson's interest in literature from both sides of the Atlantic. He initially studied it in college before the performing arts led him down a different path. Supposedly, directing a play when he was 18 was the spark that started it all. Then, like many a British actor, he attended the RADA, from which he graduated in 1973.

A couple of years later, he made his acting debut. Unlike most of his contemporary colleagues, Wilkinson stepped in front of the camera before consolidating a career on stage. Though an episode of 2nd House reached audiences first, The Shadow-Line marked the start of a prolific career, joining a 27-year-old Wilkinson with Polish auteur Andrzej Wajda for an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's homonymous novel. It's a seafaring drama so preoccupied with inertia it lets itself become inert, floating stagnantly while a sensational Wojciech Kilar score bristles against the stillness.

Though he was a novice, Wilkinson plays the third most important character, an enigmatic cook who seems impervious to the same sickness that consumes the remaining crew. It's a supporting part that could be flattened into hollow eeriness if not for the actor's ability to ground himself and the story. His cook Ransome is a slippery presence, ambiguous in intention but never less than human. Though people wouldn't have known it in 1976, the performance represents an excellent introduction to Wilkinson's approach to drama.

SENSE & SENSIBILITY (1995) Ang Lee

SENSE & SENSIBILITY (1995) Ang Lee

The following years would see to it as the actor went from the stage to TV and back again. His West End debut came in 1980, and his first major awards citations came soon after. In 1981, he was nominated for playing Horatio in Hamlet at the Laurence Olivier Awards, while 1988's An Enemy of the People earned him the same honor, as well as some of his best reviews ever. By the 1990s, Wilkinson was nearing his 50s and ready for an overdue breakthrough. It started on TV, through his stint as DI Resnick, and the limited productions of Martin Chuzzlewit and Cold Enough for Snow.

For Oscar obsessives, Wilkinson came to prominence in small parts within prestige British prestige fare. Think In the Name of the Father and Sense & Sensibility, where his death in the first scene kickstarts the Austenian plot. Throughout these turns, he's never disruptive or distracting, fleshing out his characters so they feel steeped in the narrative's reality, their existence invisibly extending beyond the film's limited frame. He never overplays his hand, and seldom calls too much attention unto himself. In other words, though virtuosic, Wilkinson avoided scene-stealing.

THE FULL MONTY (1997) Peter Cattaneo

THE FULL MONTY (1997) Peter Cattaneo

And then came The Full Monty, one of those unlikely hits that took the world by storm in the 1990s. It was a time when British comedies became fashionable beyond borders, resulting in such magnificent bounties as this film's four Oscar nominations. Wilkinson was probably close to a nod, earning best-in-show notices from critics impressed by his ability to negotiate good humor with desolation. In a tale of unemployed steel workers putting on a striptease act, the thespian is as ready to highlight the premise's fun as to suggest a deep shame more tied to economic precarity than the stripping itself.

Tom Wilkinson won the Best Supporting Actor BAFTA that year and shared the SAG for Outstanding Cast with his colleagues. He'd return to the awards conversation with Shakespeare in Love the following year. Playing a financier whose mercenary menace crumbles under true passion for the arts, Wilkinson shows his range and then some. See the hints of callous cruelty that he tosses off-hand, the curiosity that sparks in his eye, the clumsiness of the fan turned star as the character steps into the play inside the film. But again, this was a small part performed without any interest in the spotlight, the sort of thing that rarely gets the Academy's attention.

IN THE BEDROOM (2001) Todd Field

IN THE BEDROOM (2001) Todd Field

For that, Wilkinson would need a more central part where his understated approach could shine under the camera's undivided attention. And so, this retrospective comes to Todd Field's In the Bedroom, a study on grief and guilt that posits Wilkinson against a plate-smashing Sissy Spacek as the parents of a murdered young man. Together, they provide an entire history of marriage, collapsing as the plot unravels until they're adrift and apart. The picture's last act is a tour de force for Wilkinson in particular, seeing him turn from bereaved patriarch to avenging angel.

The man's actions are coldly observed, with neither the camera nor the actor latching onto any prescriptive morality. It's all the more unnerving because of it, and in a world where Denzel Washington wasn't without a Best Actor trophy by 2001, Wilkinson might have even won Hollywood's most coveted trophy. Despite the triumph, Wilkinson wouldn't become a leading man after this. Sure, he sometimes took on central parts, as in Jane Anderson's Normal or Julian Fellowes' Separate Lies, but it was in the margins that the actor appeared most comfortable. Good thing he was brilliant at it.

Part of me wants to keep writing about every one of Tom Wilkinson's supporting performances in the 21st century, for they all earn admiration. He's so oily and unpleasant in Girl with a Pearl Earring, while providing one of the sharpest narrative threads in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. For Batman Begins, he put on a mobster affect, all the more intimidating because of how unostentatious he remains, unbothered by the stylistic codes of comic book villainy. He was similarly perfect in The Ghost Writer, conflicted fatherly in Belle, theatrically on point for Wes Anderson.

MICHAEL CLAYTON (2007) Tony Gilroy

MICHAEL CLAYTON (2007) Tony Gilroy

That said, three performances demand particular attention from Tom Wilkinson's career in the new millennium. Going in chronological order, Michael Clayton comes first. The 2007 thriller earned Wilkinson a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination and remains one of his most impressive feats. Though playing a bipolar lawyer in a crisis of conscience, there's an elegance to how he suggests instability, managing to be both the inciting chaos of the narrative as well as its bastion of reason and right. Other actors might've made the character into a circus attraction. Wilkinson lets him be something akin to a tragic hero.

After that big-screen miracle came the actor's most sublime small-screen turn. It's his performance as Benjamin Franklin in Tom Hooper's John Adams miniseries, an example of Wilkinson's ability to play political figures caught in permanent argumentation, every talk a transaction, every gesture a balance between the projected persona and genuine personality. Seeing him, you understand why Franklin became such an important figure. You get the weight of influence and the diplomatic genius. You also catch the man existing in his fragile flesh rather than a mere abstraction in History books.

THE BEST EXOTIC MARIGOLD HOTEL (2011) John Madden

THE BEST EXOTIC MARIGOLD HOTEL (2011) John Madden

Finally, Wilkinson also shined in the first of the Best Exotic Marigold Hotel films. Indeed, he plays the picture's most emotional storyline, a closeted gay man returning to the place where he once found love and left it behind. He navigates the aches of old memories clashing against one's confrontation with mortality, a tender meditation that feels far too profound to survive within a commonplace dramedy. But even beyond that 2011 success, Wilkinson continued to thrive, going so far as reprising his Full Monty character for a Disney+ miniseries.

The six-episode sequel shall remain Tom Wilkinson's last role, a final farewell for a thespian who gave us so much while he was alive. Because he was such a consummate ensemble player, he might not be remembered as a star. I don't see anything wrong with that, though. As said before, we need more old-school character actors, we need more like Tom Wilkinson, who will be dearly missed. Thank you for everything.