Distant Relatives: Limelight and Hugo

Friday, February 24, 2012 at 9:30AM

Friday, February 24, 2012 at 9:30AM Robert here with my second Distant Relatives of the week, making sure the series covers the major Oscar contenders before the big day (sorry The Help). Plus, Hugo arrives on DVD Tuesday for those of you who haven't yet seen it.

Two weeks ago I compared The Artist to Sunset Blvd delighting in the contrasts between the inspirational modern film and the cynical classic. Hugo might have been an even better point of comparison to Sunset Blvd since both are about young men discovering titans of the silent era whom time has forgotten but a film has many fathers and I'm intrigued by the relationship between Hugo and a film like Charlie Chaplin's Limelight. Like Hugo, Limelight is a film about a rediscovered artist, that's really a film about love of silent cinema that may really really be about the filmmaker himself.

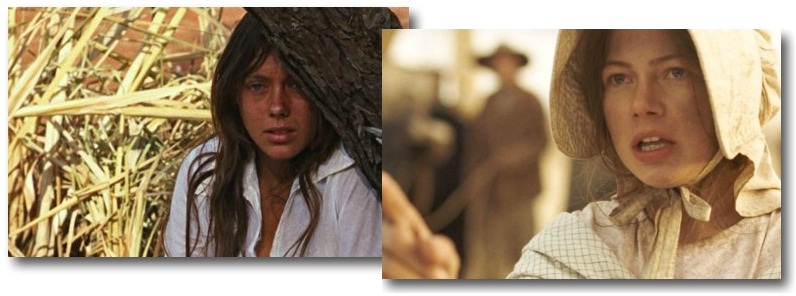

There must have been several things compelling Martin Scorsese to adapt the book "The Invention of Hugo Cabret": Scorsese's legendary love of cinema, his passion for the cause of film restoration and preservation, and as his story goes, a desire to make a children's film that his own child could watch. But might the tale of an underappreciated filmmaker from years past held more personal resonance? In Hugo our hero Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield) discovers the presence of Georges Méliès (Ben Kingsley) through a series of adventures in the train station in which he lives. Through further adventures the young boy attempts to bring about Méliès rediscovery.

In the age of the home viewing and the internet it's pleasant to believe (however optimistically) that we don't forget such brilliant filmmakers. But how often must Scorsese have heard in recent years that his best, most productive years and most influential films were behind him. In fact, any of his contemporaries from the 1970's, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, have heard the same from time to time or quite often. And while we may not forget their seminal works as the world forgot the work of Méliès, how quick are we to dismiss them as great artists of the past or bores of the present.

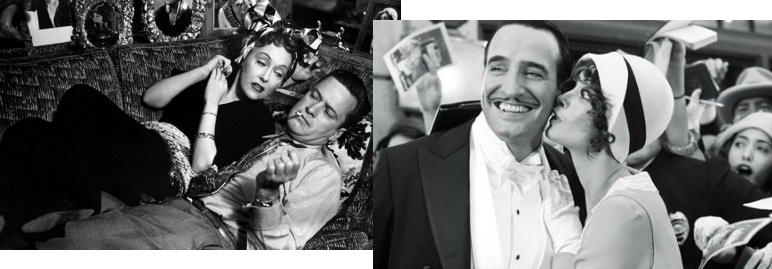

Speaking of which, Charlie Chaplin made Limelight in 1952, almost twenty-five years after the arrival of talkies forever changed his canvas. Of course he hung on as long as he could, making silent films or semi-silents until the late thirties and then scoring a couple of talkie hits. But by the time the fifties came around, Chaplin was most definitely yesterday's news. It's not surprising that he wrote a film about a long forgotten clown named Calvero (Chaplin) rediscovered by a beautiful ballerina (Claire Bloom) and eventually given the tribute he deserves. Of course the film isn't about the art of the clown as much as it is the art of the silent comedian, punctuated by final performance by Calvero and his old partner (played by Buster Keaton). And of course the film isn't about anything as much as the lost prestige of Chaplin who was being banned from the US for his "communist sympathies" just as Limelight was being released.

In these films about young characters who discover old artists, it's entirely possible that Scorsese and Chaplin feel a kinship with the characters of both generations. While it's debatable that Scorsese sees similarities between himself and Méliès, I don't doubt that he knows what it's like to be Hugo, the young boy whose life is defined by the magic of movies. And Chaplin may not be an exact match with the ballerina who falls in love with a clown, but he certainly has an understanding of being a performer whose life is altered after discovering the brilliance and art of real clowns.

What's further telling is how the young people in both films lead sad, dreary, almost hopeless lives until they discover the magic that the rest of the world has forgotten. For Chaplin and Scorsese, these films are a look back at their pivotal moments and a look forward at those who may very well be discovering them, and perhaps a plea for our own lives and our own sakes, not to forget the magic. In an odd way they're both true stories too, however embellished. Méliès was re-discovered and re-appreciated in his life. And the real-life counterpoint for Calvero the clown had his moment too.