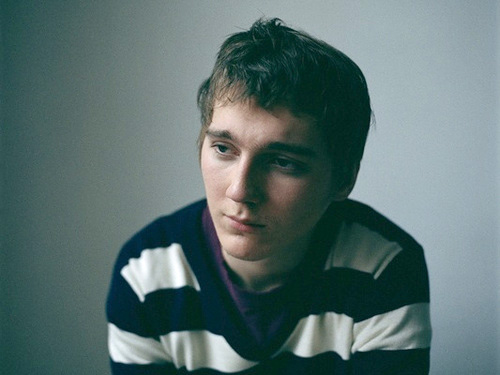

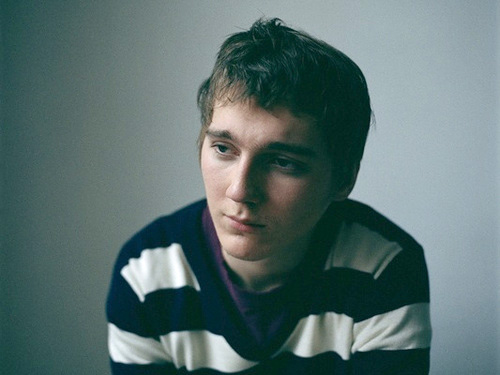

Craig from Dark Eye Socket here with Take Three. Today: Paul Dano

Take One: The King (2006)

Disgruntled discharged Navy man Gael García Bernal rules the roost in James Marsh’s dark religion-themed indie The King. But Dano, as the dutiful square peg brother/son in the family Bernal infiltrates, does attempt a one-man, god-fuelled backyard coup, much to his own expense. The film is partly a hothouse take on Cain & Able and partly a nod to bad-couple movies like Badlands (brooding Bernal and Sissy Spacek-a-like Pell James doing bad things in cars). Dano’s Paul Sandlow, a pastor's son, sings and plays guitar in a Jesus-heavy, quality-light church rock band. That’s when he’s not pressuring the school heads into accepting his curriculum on Intelligent Design over Evolution. Paul’s doe-eyed sappiness appears to hide a certain cleverness yet, oddly, he’s one of the most sympathetic personalities in the film.

Dano’s performance is savvy. His dorky, modest Jesus freak teeters around the periphery of the action – spouting glassy-eyed school speeches about Him upstairs, defining smugness in a four-wheel-drive graduation gift – until emerging prominently as the plot hots up. Dano plays it all with a calm curiosity. By intuitively holding back, he manages to convey more, swerving cliché to deliver a turn replete with discomforting nuance. He may be a timid teen in a Christ crisis, but the threat of censure glints in his eye. He shouldn’t have banked on the promise of a “brother’s” honour. After his fateful face-off with Bernal halfway in, Paul’s merely a face on a missing poster and the subject of Bernal’s less-than-guilty conscience. But he makes each scene count before being sent down the river.

Take Two: Cowboys & Aliens (2011)

Dano must love dust. He’s sure seen enough of the stuff on screen in recent years. He saw blood and oil spilt in it in There Will Be Blood (see below) and stomped soil on the pioneer trail for Kelly Reichardt in Meek’s Cutoff earlier this year. And in theatres over the past few weeks he’s been kicking up a fuss in the stuff in genre mashup Cowboys & Aliens. Dano pops up early on as Percy Dolarhyde, the troublesome drunk son to local grump-on-horseback Harrison Ford. Their rocky filial relationship is a part of the background to the alien-busting action. But when Percy is lassoed by the rootin’ tootin’ extra terrestrial braggarts, and whisked away for some probably dubious shenanigans, it allows Ford’s character some plot momentum.

I missed Dano’s slapdash spoiled and cowardly presence, though, and wished he’d stayed for the duration. The movie required a dependable human villain throughout, to split the difference between the ramshackle townsfolk and the interstellar menace. A late, cheeky crowbar plot device means that we can’t resume our hiss-boo heckles at Percy’s clumsy tomfoolery, but at least he re-enters the movie. In his meagre handful of scenes Dano shoots it up then shrieks it up with barmy abandon. Percy is ultimately sold short, but Dano adds another fine small performance to his filmography. As a now well-established yet still young character actor he’s continuing to pay his dues in often largely peripheral roles. Cowboys & Aliens shows, alongside Meek’s Cutoff, that he’s cornered the market in sly and sheepish movie-dust slingers.

Take Three: There Will Be Blood (2007)

It took two roles (brothers Paul and Eli Sunday) for Dano to go up against maniacal oil plunderer Daniel Day-Lewis (as Daniel Plainview) in Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosively oily There Will Be Blood. The religion theme is again present but here Dano’s graduated to fully-fledged preacher. The role very nearly wasn’t his, however. Dano only had a few days to rehearse his role as Eli, the bigger of his two parts. Kel O'Neill was originally cast, but was replaced with Dano (who was only originally down to play the smaller role of Paul) two weeks into the shoot; a total of three weeks of scenes featuring Eli and Plainview had to be re-shot with Dano instead of O'Neill. However, any casting interruptions don’t at all impede him on screen. If anything, the immediacy adds to the fevered vitality of his performance.

Paul Sunday's polite staccato-voiced calm is miles away from the disingenuously bilious bluster of Eli Sunday. Dano expertly differentiates his roles, but also allows small drip-fed shreds of doubt to enter into both Plainview’s and the audience’s minds: are they both the same brother? Neither we, nor Plainview, ever truly know. Eli’s scenes of evangelism, his casting devils out of the congregation with screams that seem to break his voice and weird, fierce strain-faced air grabs, are riveting. He’s scarily good, too, in the epilogue, when he visits Plainview with an offer. When Plainview asks “I want you to tell me you’re a false prophet,” Dano’s unblinking, knowing gaze is priceless; one expression reveals the core falsity of Eli’s faith. His opportunism and barely-concealed weakness, here as elsewhere in the film, tells us just as much about what Anderson was striving for as Day-Lewis’ performance does. Dano didn’t strike gold like Day-Lewis did, but he mined the film for all its worth – and, through one means or another, he made good on the promise of that title.

Three more films for the taking: L.I.E. (2001), Little Miss Sunshine (2006), The Extra Man (2010)

Monday, April 23, 2012 at 11:01AM

Monday, April 23, 2012 at 11:01AM

Heche’s scenes with Sean (Cameron Bright) after the friction of the plot has been replaced by psychic damage throw a puzzling curveball (the buried package!) to the remainder of the film. These moments provide us with Heche’s best, and most tense, work to date. Insidious, slightly witchy and perverse, Heche reveals a reverse deus ex machina that shows Clara to be the queasily spiteful and questionable presence of the story. Her face, shot in extreme close-up, displays a deliciously evil sheen as she devastates the young boy. On evidence here, I’m baffled as to why filmmakers aren’t snapping Heche up to play the kinds of complicated icy queens usually reserved for Tilda Swinton. Birth features an all-round stellar ensemble but if you haven't seen it recently watch it again to see Heche wrench entire scenes away from the lot of them.

Heche’s scenes with Sean (Cameron Bright) after the friction of the plot has been replaced by psychic damage throw a puzzling curveball (the buried package!) to the remainder of the film. These moments provide us with Heche’s best, and most tense, work to date. Insidious, slightly witchy and perverse, Heche reveals a reverse deus ex machina that shows Clara to be the queasily spiteful and questionable presence of the story. Her face, shot in extreme close-up, displays a deliciously evil sheen as she devastates the young boy. On evidence here, I’m baffled as to why filmmakers aren’t snapping Heche up to play the kinds of complicated icy queens usually reserved for Tilda Swinton. Birth features an all-round stellar ensemble but if you haven't seen it recently watch it again to see Heche wrench entire scenes away from the lot of them. Anne Heche,

Anne Heche,  Birth,

Birth,  Janet Leigh,

Janet Leigh,  Psycho,

Psycho,  Take Three

Take Three