Craig here with Take Three. Today: Michael Pitt

Take One: Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001)

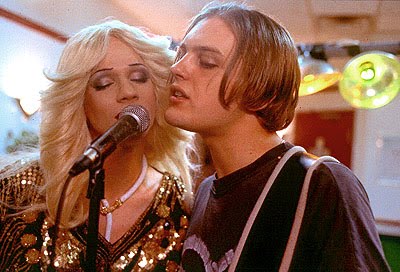

Pitt’s weedy teenage wannabe rock imp Tommy Gnosis (The Jesus freak army brat formerly known as Tommy Speck – then, very nearly, Tommy Ache) got to grapple with Hedwig’s Angry Inch in unconventionally inventive ways back in 2001. John Cameron Mitchell’s slip-up-operation rock opera, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, was like nothing else on screen at the time. If you could avert your eyes from internationally ignored “icon” Hedwig’s shining beacon of starlight, then hidden in the flared remnants, and on the sidelines, was Pitt’s Tommy. He was initially willing to dote on her every word but eventually reluctant to acknowledge his own sneaky appropriation of her back catalogue. He became the big star; Hedwig toured the fish restaurants of America.

Pitt does the naive, overtly adoring rock moppet well. He also does the non-committal, dull-eyed whiner-singer act capably, too. In short: he nailed being a half-hearted androgynous songster on the head. His game karaoke portrayal was a bizarre squishing together of Iggy Pop, Kurt Cobain and Marc Bolan and it made for a perfect contrast with Mitchell’s gender mis-reassigned glamzilla. Pitt had the “gee shucks” drippiness down to a tee early on and the moody insouciance of a fast-rising pin-up later in the film. Pitt’s occassionally been compared to Leonardo DiCaprio (they look faintly alike), but he was destined for less starry vehicles. Hedwig was his first substantial role after a few bit parts in some notable movies, setting the left of mainstream tone.

Take Two: Funny Games US (2008)

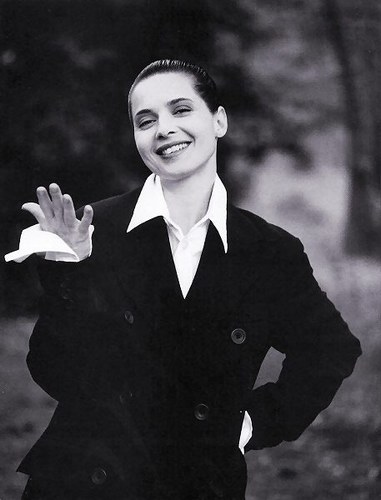

Pitt put his baby-faced Buscemi looks to ominous use in Michael Haneke’s close-to-replica American remake of his own 1997 violent image treatise Funny Games. I’m not this particular remake’s biggest admirer, but I’ll stunt the bile flow and focus on the matter at hand, the one stand-out aspect: Pitt’s performance, which was remarkable for its blandly creepy conviction. Brady Corbet’s less assertive Peter was fine. But Pitt, as fourth-wall-breaking smiling Paul, had the film – just like the terrorised family at its centre – under his thumb with his politely negotiated terror. He was the sociopathic preppy-styled ringleader; a blond, blank-eyed menace.

Pitt brings out the duplicity innate in his character through careful use of body language and an array of insincere facial expressions (a slyness you can also see in his Murder by Numbers and Boardwalk Empire roles). Rid of his floppy-fringed slacker locks and the pouting hipster tics of other films, with hair slicked down in Aryan tidiness and his lips curled into a smug half-smile respectively, he projects just the right amount of playful goading. He fleshes out what was essentially a second-hand scolding message character. By the time he’s playing God – and, by proxy, director – by rewinding the action to fit his own murderous MO, Pitt has quite literally won his not actually all that funny game. Without him, Haneke’s lofty polemic loses something integrally dark.

Take Three: Last Days (2005)

He certainly looked like teen spirit. And he certainly sounded like teen spirit. But whether he really, truly smelled like teen spirit is open for debate. Pitt played jaded and degraded rock icon Blake, a rather transparent stand-in for Kurt Cobain, in the third entry in Gus Van Sant’s loose death tetralogy. (Gerry, Elephant and, slightly less a part of the gang, Paranoid Park being the others.) Some folks got terribly roiled up by “their” favoured generational spokesperson being portrayed in such an irregular fashion, other folks went with Van Sant’s tonic poem and embraced his loose interpretation of a famous life self-terminated too early. Although Blake was our main focus, Pitt ensured we weren’t privy to everything his portrayal represented. I’m Not There was used for Todd Haynes’ experimental Dylan biopic, but it’s a more apt title for this portrait of rock iconicity. Or He’s Barely Audible.

Pitt achieves a lot by doing little on screen: stumbling his way around his crumbling mansion with a shotgun, mumbling his way around a conversation with a pair of Mormon callers, looking fed up when Kim Gordon pops in for a chat, playing hide-and-seek with Asia Argento, making himself scarce when Lukas Haas and co. drop by unannounced, sharing a moment of tender clarity with a mini clowder of stray kittens. He draws attention by shielding himself from us; we barely see his face. When we do see his face, it’s a blank slate - a pale, unkempt presentation of incoherent mannerisms. It’s kind of Method acting, but kind of not. (Stripped Method? Method Undone?) It's the shuffling, vaporous presence itself that makes an impact. Portrayed this way, Blake is always a scruffy enigma, there to curiously mull over or ignore as we see fit.

Thre more key films for the taking: The Dreamers (2003), The Village (2004), Silk (2007)

Sunday, April 24, 2011 at 8:01PM

Sunday, April 24, 2011 at 8:01PM