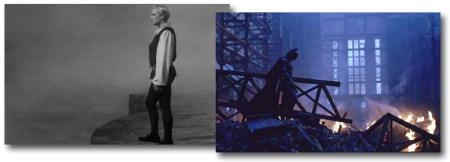

Distant Relatives: Hamlet and The Dark Knight

Thursday, March 17, 2011 at 5:20PM

Thursday, March 17, 2011 at 5:20PM Robert here, with my series Distant Relatives, where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through a common theme and ask what their similarities and differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema.

The Laughing Fishmonger

Of course I’m not the first person to notice a similarity between Batman and Hamlet. While the Caped Crusader of Gotham officially owes more of his inception to Zorro, the themes of his story, the conflicts that keep us coming back owe much to Hamlet, if not directly than indirectly as a model of the same story of a man driven by the “virtue” of vengeance.

Outside the stories, as cultural institutions, these two tales have much in common. Both have inspired endless versions across multiple media. Both are told over and over and over again (demand for more is considerable). Both provide endless fodder for investigations into the human psyche. These two films are stories of heroes and villains that force us to wonder really: what is a hero?

Cape, cowl, tights, temper

We can start with the superficial similarities: two silver spooned children, dead parents, promises to seek retribution, manic dispositions put upon, villains everywhere, corrupt cops (if you’re so inclined to consider Rosencrantz and Guildenstern). There are similarities to be found everywhere if you wanted to stretch hard enough. You could find an equivalence between Hamlet’s third act travelling players ploy and the Gotham police department’s fake funeral plan. Two “shows” of reality meant to make the bad guy drop his guard.

But why the 1948 Laurence Olivier version and the 2008 Christopher Nolan interpretation? Olivier’s pared-down story lacks over-conceptualization or ornateness making it a good starting point, it’s almost the “control group” of Hamlets. More important to the comparison though is The Dark Knight, which kicks into high gear a concept hinted at by Batman Begins. That is to suggest that the super-villainy bubbling up is a direct result of Batman’s existence. Sure, other cinematic adaptations have played a bit with the “you made me” paradox but quickly dismissed it (suggesting The Joker killed young Bruce Wayne’s parents isn’t criminal because it rewrites Batman canon but it does whitewash the complexity of the character and underscore his hero status.) But Nolan is almost primarily interested in the ripple effect of Batman’s quest for justice and how like Hamlet’s vengeance it sends everything spiraling out of control.

"You've changed things... forever. There's no goin' back"

An equal and opposite reaction

What is the worst result, the highest tragedy of this downward spiral? The death of the innocent, most specifically the love interest of course. Ah, the love interest, Rachel Dawes and Ophelia, pushed away by our hero, caught up in the whirlwind of chaos he has created. The story needs a sacrifice and they’re it. And in both cases, their deaths propel us into another theme that Hamlet and The Dark Knight want to explore. The corrupting influence of grief sends both Harvey Dent and Laertes into the hands of evil just as easily as their tragedies propelled Bruce Wayne and Hamlet toward good... or should we say “good?” since all involved are feeding on their emotional instability to fuel their hunt for those who they consider responsible. The line between good and evil depends entirely on your perception of the big picture (and whether you see something more forgivable about an unjust death in the pursuit of justice than one in the pursuit of power.)

This is probably why the Hamlet and the Batman tales have such staying power. Because these questions have plagued humankind through centuries of the war, terrorism, crime, punishment, and the pursuit of justice. Yet neither of these films intend to give us moralized answers. There are no Gandhi lessons about an eye for an eye leaving the world blind here. Sure, we can see the results for ourselves, but our heroes are still meant to be heroes. What’s the last thing said about Hamlet? He’s called a “noble prince.” The last thing said of Batman? He’s called “the hero Gotham deserves.”

Hamlet would have illegally wire tapped all of Denmark's phones if he'd had the technology

There are, of course, differences between the two as well. Batman has more explosions. Batman has cooler villains more intent on anarchy (although Claudius’ apathy toward the Fortinbras threat isn’t exactly the model for great leadership). What Hamlet has, that Batman does not is doubt, at least according to Olivier who pegs his protagonist's problem as constant waffling declaring upfront that “This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” Batman has no such qualms. Perhaps that’s the power that makes him a superhero, his superhuman determination that what he’s doing is unquestionably right. In that sense maybe Hamlet holds the moral high ground. Then again later interpretations of the character, unbound by the Hayes Code were more singular in their bloody thoughts and Hamlet himself is still directly responsible for several deaths while Batman has a code against killing, and so the pendulum swings back the other way.

Perhaps the one thing we can take from the comparison is that the audiences of 2008 just like the audiences of 1948 or 1600 for that matter really are looking for a complex hero, an honest story, and a good fight at the finale.